Tiny House, at Westport County Playhouse

Happy 4th of July, that testament to the foundational myth of the United States of America. During this year’s Independence Day, Westport County Playhouse returns to active theater with Michael Gotch’s Tiny House, a dramedy set on a 4th of July lived “off the grid.” It’s a nice bit of irony. The show is streaming theater that takes us to the remote mountainous home of a couple—Sam & Nick—who purport to have withdrawn from corporate America and the distractions of internet culture. Which means they wouldn’t be likely to access theater like this.

The play takes its cue from our contemporary moment of crisis in which catastrophe looms and methods of coping have become the order of the day. And that’s apropos, as streaming theater, in which the remote audience attends theatrical content prepared digitally, was a part of many people’s quarantine experience. The fact that as of this week most theatrical restrictions of the pandemic have been lifted (for fully vaccinated companies) by Actors Equity, such as bans on actors occupying the same theater space, makes the Westport production already feel dated, part of last summer’s situational awareness.

And, on that note, just to get it out of the way: the digital green-screen version of this play is an oddly hybrid experience. The actors are all in different spaces trying to keep each other in believable eyelines, and efforts to create the illusion that they are in contact are oddly intrusive, like trying to hide the strings on puppets. Otherwise, there’s a detailed backdrop of a tiny house (you know, those cramped, small-footprint, ingenious boxes in which bourgeois accoutrements are reduced to the dimensions of a cruise ship’s cabin for a life free of excess, clutter, and waste), and very ripe nature shots, like a mountain/valley view aimed to induce vertigo and a forest verdantly ancient as only digital imagery can be. The Westport show is better than Zoom theater but not as satisfying as actors on stage together relayed by video, as at TheaterWorks this season. Even so, there’s considerable interest in contemplating how director Mark Lamos and his team pulled off this virtual theater-space which has its own odd charm. (And cheers to Westport Country Playhouse for continuing on; Tiny Houses opened on June 29, exactly 90 years since WCP first opened its doors, on June 29, 1931, so it certainly has been around for some trying times.)

Sam (Sara Bues) and Nick (Denver Milord) in Westport County Playhouse’s production of Tiny House by Michael Gotch

The play itself is a hodgepodge of the edgy, the erratic and the aiming-at-entertaining. Nick (Denver Milord) and Sam (Sara Bues), the well-intentioned male-female couple hosting, have, of course, their issues, notably with Sam’s recovery from a miscarriage. She’s feeling vulnerable and not up to what is bound to be an abrasive visit from her mother, Billie (Elizabeth Heflin), a divorcee now living with her former brother-in-law, Larry (Lee E. Ernst). Sam’s father has been jailed for perpetrating “the biggest Ponzi scheme since Jesus walked the earth” (it’s a neat line and gets trotted out three times), and there’s lots of bad feelings and traumatic scarring about that.

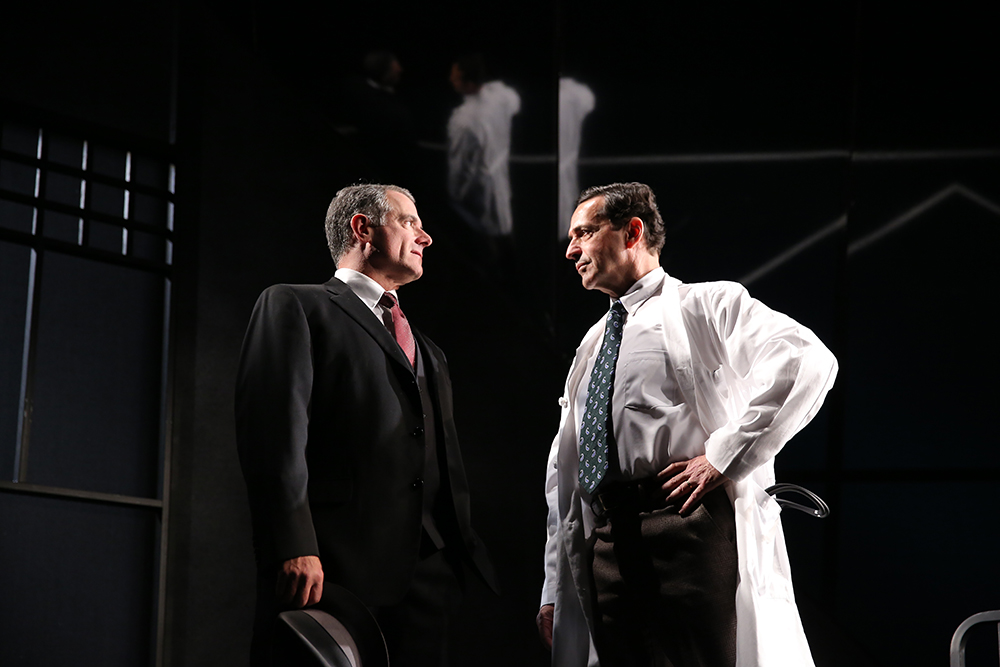

Larry (Lee E. Ernst) in Westport County Playhouse’s production of Tiny House by Michael Gotch

The “zany neighbor” role is given a switch in presenting the grim and mysterious Bernard (Hassan El-Amin), an armed hunter of marmots who may have been CIA and is concerned with the approaching “zero hour” of some indefinite apocalypse. We might assume this is just gun-nut fantasy, but he’s listening to “chatter” and everyone but Billie voices anxiety over the state of the world—whether climate change or anxiety-inducing news bulletins in general. Bernard helps keep alive the notion that this play is about more than awkward company on a holiday weekend but mainly he just sets up the punch that is the ending note of the play.

Bernard (Hassan El-Amin) in Westport County Playhouse’s production of Tiny House by Michael Gotch

The family sparring gets its most intense when Billie, in youth a bunny at Hef’s Playboy mansion, gets into an escalating aria of jabbering grievance with Nick that is the aural equivalent of speed-scrolling leftist 30something (Nick) and rightist Baby Boomer (Billie) flashpoints simultaneously. Like much in this play, it’s overwrought to little purpose. Early on, Nick has lines that make him a fun take-off of the intensely concerned and focused man-child of our times, so keen to offset the mess elder generations have made of the world. But the elder generation here, but for Billie, are little more than wan comic relief sporting hippier-than-thou wiftiness. Larry, in Ernst’s energetic performance, might add a loose cannon’s surprises but he collapses into the abyss of truly zany neighbors Win (Stephen Pelinski) and Carol (Kathleen Pirkl-Tague) who play on the laughs automatically conjured by Renaissance festivals, Tolkienesque elf-folk and hallucinogen-laced vegan tortes. Sigh.

Win (Stephen Pelinski) and Carol (Kathleen Pirkl-Tague) in Westport County Playhouse’s production of Tiny House by Michael Gotch

When the transmission’s sixty-second intermission arrived I was already wondering if—as with a game’s halftime—there would be a turn-around or if it was already over. In the second part, we get to the payoff of Gotch’s best idea: that the unsustainable civilization bequeathed us by twentieth-century capitalism is the equivalent of a giant Ponzi scheme that has suckered us all. That, to me, was the ideological upshot of Sam’s harangue to her mother about how bad it is to grow up as the besmirched daughter of a con-man and national disgrace. Bues gives the speech her all but it’s not her fault that the lines don’t give her much awareness beyond poor-pitiful-me whining and a self-satisfied jab at Mom (whose own woe-is-me depiction of life after Shamalot we’ve already heard). Both Bues and Heflin almost convince us we’re seeing the kind of self-exposure with consequences that drama sometimes achieves, but the ploy of having Nick overhear a certain statement by Sam feels utterly contrived—and nothing comes of it anyway.

Sam (Sara Bues), Nick (Denver Milord), Billie (Elizabeth Heflin) in Westport County Playhouse’s production of Tiny House by Michael Gotch

And that’s the nature of this particular gathering: some good ideas, agreeable performances, digital sleight-of-hand (some of which works well), in service to the baleful thought that we’re basically fiddling while Rome burns. Maybe so, but more fiddling with the script would not be out of order. As it is, Tiny House aims to be a play of its moment that only manages to be a play for the moment.

Tiny House

By Michael Gotch

Directed by Mark Lamos

Scenic Design: Hugh Landwehr; Digital Scenic Design: Charlie Corcoran; Costume Design: Tricia Barsamian; Original Music and Sound Design: Rob Milburn, Michael Bodeen; Sound Edit, Mix and Additional Sound Design: M. Florian Staab; Editor: Dan Scully; Director of Photography: Lacey Erb; Wig Design: Christal Schanes; Production Stage Manager: Matthew Marholin; Assistant Stage Manager: Ellen Beltramo

Cast: Sara Bues; Hassan El-Amin; Lee E. Ernst; Elizabeth Heflin; Denver Milord; Stephen Pelinski; Kathleen Pirkl-Tague

Westport Country Playhouse

June 29-July 18, 2021

Streaming On Demand