Review of Indecent at Yale Repertory Theatre

Indecent, the first of three world premieres at the Yale Repertory Theatre this season, presents two striking tableaux: first, a group of players arrayed before us, introduced by the stage manager Lemml (Richard Topol), drip sawdust from their cuffs. And, near the close, a cascade of rain that brings to life the oft-mentioned rain scene in Sholem Asch’s The God of Vengeance, the early twentieth-century Yiddish play that acts as the occasion for Indecent’s revisiting of theater history.

Between those two poetic theatrical moments, Paula Vogel’s new play, directed by Rebecca Taichman, presents the fortunes of Asch’s play, a play that, in 1923 when it finally reached Broadway in a truncated version, was prosecuted as “obscene, indecent.” Sure, the play features a brothel and a lesbian love affair and, maybe, sacrilege, but the real reason for suppression, someone in Vogel’s play suggests, was “Jews on Broadway.”

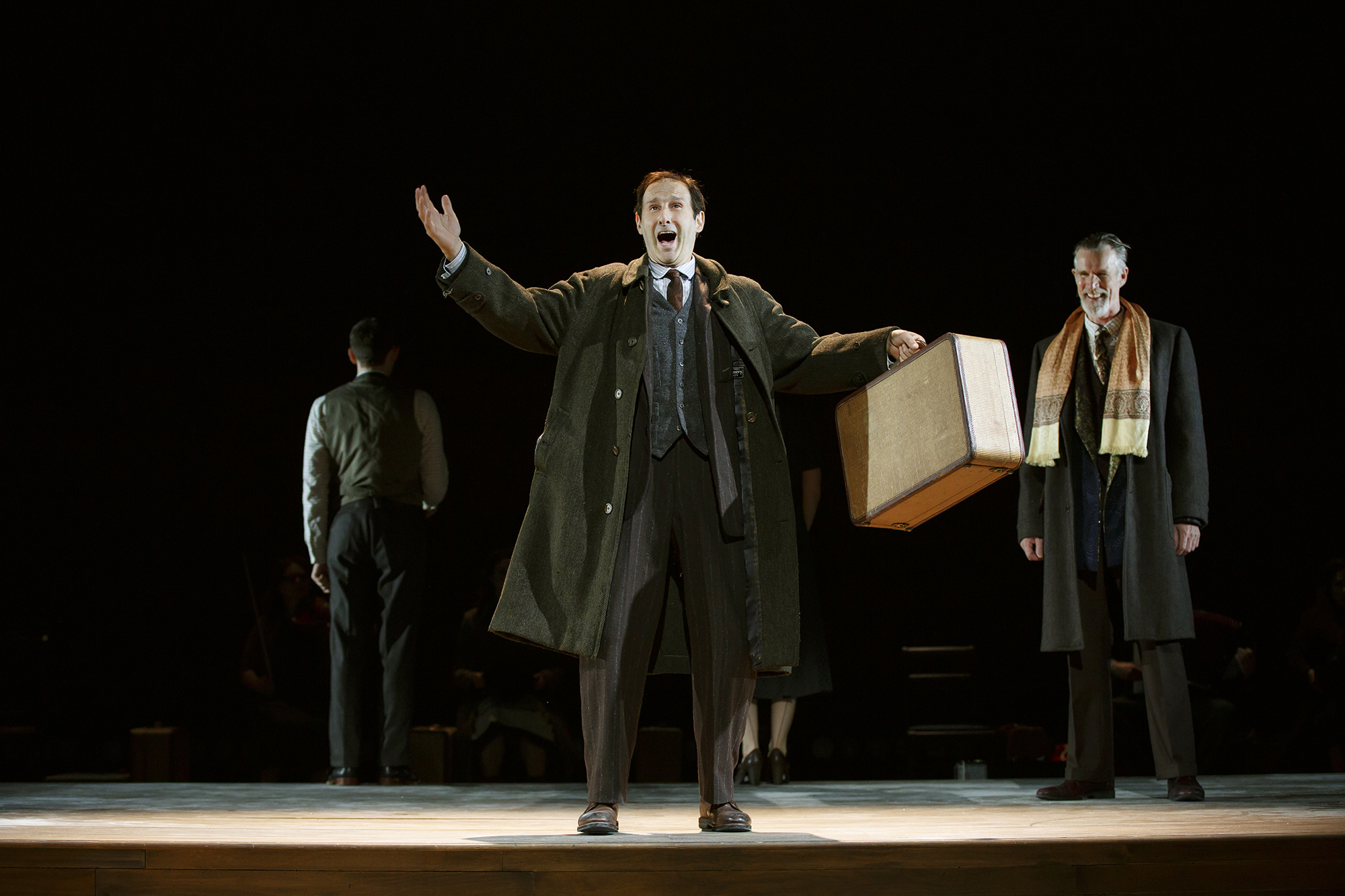

Steven Rattazzi and the cast of Indecent

Though presented with quick scene changes, moving from 1907 to 1952, by a cast of 7 actors and 3 musicians with scant use of props and with many minor roles to keep track of, Indecent is oddly static. Vogel employs the vignette approach familiar from her regional staple A Civil War Christmas and tries to work in as much historical detail as possible in a wealth of brief scenes, most supported by subtitles telling us when and what.

Along the way we get the first awkward reading of The God of Vengeance by a group of uncomfortable men; Asch’s play’s dramatic close in a swift “onstage” montage in a number of major European cities; the offstage romance between, first, Ruth (Adina Verson) and Dorothee (Katrina Lenk), then between Virigina (Verson) and Dorothee, shaped by the onstage romance of the characters they play; the troupe’s arrival in the U.S. via Ellis Island; and the fortunes of European Jewry, most particularly and movingly when Lemml, who remains a staunch champion of the play from that first reading onward, stages the play in the Lodz ghetto created by Nazi occupation. Asch’s play, for Lemml, is one of the greatest ever written and, since Lemml is such a sympathetic character, we want to believe him.

Max Gordon Moore (left), Richard Topol (front), Tom Nelis (right)

Still, Indecent’s handling of The God of Vengeance makes the earlier play seem at times rather quaint and at other times an incendiary text. It’s hard to say, given what we’re shown of it, how we would respond to it if we were to sit through it, but it’s also hard to say whose attitude toward the play—Asch himself doesn’t seem to think it’s sacrosanct and approves cuts the way anyone who wants to get his play on Broadway might—we should accept. Vogel and Taichman mainly approach the play through its sexual politics, so that a lesbian love—which is enough to cause Asch’s patriarch Yekel to condemn his daughter Rifkele to “a whorehouse”—emerges as the theme to be duly noted and celebrated. Thus the key scene between Rifkele (Verson), the virgin, and Manke (Lenk), the prostitute, is mediated through various enactments and distortions before the final rain scene evokes the highly romantic alignment at the heart of Indecent.

Adina Verson, Katrina Lenk

Working against whatever dramatic gold might be found in all this retrospective prospecting is Indecent’s somewhat clunky staging. It’s not simply that the characters tend to be caricatures—the big name actor, the vain and clueless name actress, the intense author, the earnest ingenue, the self-conscious lesbian—but that the acting doesn’t help. Playing all the senior male roles, Tom Nelis seems anything but a Yiddish patriarch, while Max Gordon Moore, usually an asset, never seems to inhabit Asch. The female roles fare somewhat better, particularly Lenk’s bit of German cabaret, and the eros-through-acting between Verson’s Virginia and Lenk’s Dorothee. As Lemml, Topol’s focused performance adds the strongest note of advocacy for theater as identity.

Plotwise, movement between scenes is more didactic than intriguing or entertaining. Time marches on and things happen. Eventually, (we know) the play will be resurrected from the dustbin of history by a well-intentioned contemporary playwright. We’re not privy to any scenes from the rehearsals of Indecent, but we do get a final, fairly egregious scene that name-drops Yale as a goyisch bastion from which Mr. Rosen (Moore) travels to do homage to Asch (Ellis) just as McCarthyism is getting underway. It’s as if Vogel’s fertile mind has been tasked with working-in every possible historical connection that might make Asch’s play worthwhile and memorable, though without getting “meta” and commenting on her own appropriation. But by keeping Yiddish culture at arms’ length—we see the language in subtitles but hear precious little onstage—Indecent doesn’t recreate a bygone culture as much as it might, and by rushing through every era with the same even tone, the play’s texture becomes a bit diffuse.

Indecent’s themes, which are important and varied, deserve better. In the end, Indecent is little more than decent.

Indecent

Written by Paula Vogel

Created by Paula Vogel and Rebecca Taichman

Directed by Rebecca Taichman

Choreographer: David Dorfman; Composers: Lisa Gutkin, Aaron Halva; Music Director: Aaron Halva; Scenic Designer: Riccardo Hernandez; Costume Designer: Emily Rebholz; Lighting Designer: Christopher Akerlind; Sound Designer: Matt Hubbs; Projection Designer: Tal Yarden; Dialect Coach: Stephen Gabis; Fight Director: Rick Sordelet; Yiddish Consultant: Joel Berkowitz; Production Dramaturg: Amy Boratko; Casting Director: Tara Rubin Casting; Stage Manager: Amanda Spooner

Cast: Richard Topol; Katrina Lenk; Mimi Lieber; Max Gordon Moore; Tom Nelis; Steven Rattazzi; Adina Verson; Musicians: Lisa Gutkin; Aaron Halva; Travis W. Hendrix

Yale Repertory Theatre

October 2-24, 2015