David Byrne & St. Vincent, The Beacon Theater, NY, 9/26/2012

Step into the Beacon Theatre and you’re hit with layer upon layer of eye-popping visuals: huge bronze doors, white marble floors, a Classical pastoral mural over the entrance, mahogany wood paneling, gold and burgundy wool carpeting, gold-tasseled draperies, and gilded everything-in-sight. And all of this is before you get to the auditorium. Once inside you’re treated to 30-foot-tall sculpted goddesses flanking the stage (I’m guessing Athena based on the long spear she’s holding), which themselves are flanked by murals of an elephant-led Eastern caravan. Over the stage hangs a Moorish-inspired decorative flap reminiscent of a circus big top, topped off by a riot of Art Deco and Arabesque decorative patterns, a 900-pound chandelier, and a gigantic ornately-carved pendant.

Designed by Chicago architect Walter W. Ahlschlager and opened to the public in 1929, New York’s Beacon Theater is both reassuringly stately—reassuring because of the steep ticket prices—and wonderfully tacky. The American Institute of Architects describes it as “Greco-Deco-Empire with a Tudor palette” while the New York Times goes with a “pastiche of Greek, Roman, Renaissance, and Rococo elements.” Built as a vaudeville palace—vaudeville must have been the perfect counterpart to the Beacon’s visual aesthetic, a democratizing mashup of ‘high’ and ‘low’ arts, entertainment and exploitation—the theater has since played host to everyone from the Allman Brothers to ZZ Top, from the Dalai Lama to Louis C.K. In other words, the Beacon contains multitudes, and contains them in a way that’s distinctly American.

Enter David Byrne and St. Vincent, aka Annie Clark, making a two-night stand at the Beacon in support of their first album together, Love This Giant (4AD). It’s a great pairing. Both might appear under “art damaged” in the dictionary—Byrne in the 1970s and 80s, and St. Vincent today. Both are known for music that’s austere one minute and feral the next (“feral” is probably the best word for St. Vincent’s guitar playing as a whole) and for lyrics that range from unsettling to playful. If they come across a little stiff at first—Byrne, St. Vincent, and the Beacon—it doesn’t mask their underlying weirdness for long.

Of course David Byrne pioneered the whole buttoned-up/unhinged thing—best captured in audiovisual form by Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense. The Beacon show has some interesting parallels to the Talking Heads concert-doc masterpiece. The stage is filled with musicians, dressed in black and white, and each song is treated as its own mini-theater piece with distinct lighting and choreography. The ten-piece band includes eight brass players, a drummer, and a keyboardist/percussionist. Most of the musicians are fully mobile, with choreographer Annie-B Parson taking full advantage. She arranges them in lines, clusters, and circles, draped across the floor at the beginning of one song, facing off in two groups like the Jets and the Sharks in the next, their formations attuned to the unusual rhythms and textures. And for her part St. Vincent creates a new signature move—a variation on the duckwalk except it’s more like a centipede missing 98 of her legs.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJ4c1yEBI6Y&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

The show opens with a baritone sax melody weaving in and out of the brass section. David Byrne enters over their stuttering rhythms, wondering who will share his taxi, who will help a dying soldier, who exists inside of him (the song is called “Who”). Suddenly, the nervous sonics drop away and St. Vincent sings over a shuddering drum line, ‘who is an honest man?’ Her melody is meandering and disorienting, much like one of her guitar parts, but it’s seductive nonetheless. In this song as elsewhere, the brass ensemble shifts between enveloping slabs of sound and dancing, intertwining lines. This interplay is the unique sonic thumbprint of the concert and of Love This Giant. It’s a distinct sound, but it contains echoes of the American pop music past and nods to world music genres ranging from Balkan brass band to Latin jazz. Again, the music meshes perfectly with the venue—a relic that seems new and strange.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NsdBKbQy_Pw&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

In the songs they’ve written together, Byrne and Clark make heavy use of juxtaposition as a literary device: ‘hideous, virtuous, both of us’ for one example. Their song’s narrators find delight in the everyday—drinking coffee, doing laundry, lost in reverie on 30th Street—while dismissing horrific events as mere annoyances. In “Dinner For Two” a party is inconvenienced by raging street battles outside: ‘Harry’s gonna get some appetizers / now he’s keeping out of range of small arms fire.’ In “The Forest Awakes,” there’s assurance when ‘bombs burst in air / my hair is alright,’ pausing to note ‘the shifting of light on the trees and the houses.’ In “Lightning,” the narrator observes a ‘funny lightning’ that she finds puzzling and thrilling: ‘But if I should wake up and find my home’s in half…I guess I have to laugh.’ Control is a recurring theme as well—maintaining it and relinquishing it—seen in images of nakedness or remaining clothed, especially when least expected: ‘we were totally naked / outside that small cafe’ vs. ‘dare to keep our shirts on / rolling in the mud.’

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAGsmPg6Qik&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

These strands come together—the magical mundane, multiple contradictions, control issues—on “I Should Watch TV.” In the song, Byrne finds agency in a passive medium, engaging with people when he’s all alone. With the help of his TV he describes losing himself, being opened up and set free by ‘the weird things that live in there.’ In some ways the song is the centerpiece of the album (its title comes from a line in the song). It’s also a rare autobiographical song for Byrne (see the clip below) that taps into a long-term obsession reaching back to his Talking Heads days. Opening with a pulsating electronic pitch—its digital glitchiness immediately sets the song apart from the rest of the album—Byrne sings, ‘I used to think that I should watch TV / I used to think that is was good for me.’ The lyrics go on to detail the view he ‘used’ to hold—a TV-based transcendentalism that advocates diving into the collective electronic slipstream, casting off one’s alienation in “the place where common people go.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EXqFu7b4oaw[/youtube]

In this regard, Byrne even goes so far as to quote from Walt Whitman—‘behold and love this giant’ is adapted from ‘I behold the picturesque giant and love him’ in the great American poet’s “Song of Myself.” Here as elsewhere, it’s not hard to see how Whitman’s transcendentalism may have inspired Byrne’s artistic worldview, but what’s most striking is the particular choice of quotation. The ‘picturesque giant’ in “Song of Myself” is a black carriage driver described in loving detail by Whitman—a brave and progressive gesture at the time, perhaps, but a gesture that today comes off as more than a little objectifying and patronizing. Byrne’s choice to quote this line, and to name the album after it, is curious. He’s way too smart and self-aware not to realize the negative implications, of course, and the lines ‘behold and love this giant / big soul, big lips / that’s me and I am this’ only highlight the diceyness of the original context. At the song’s conclusion, however, Byrne seems to cast doubt on how he ‘used to think.’ Near the two-minute mark he wonders, “How am I not your brother / how are you not like me?” as the frantic rhythms briefly cease. The final stanza makes no mention of the mass culture he idealized and exoticized before, suggesting instead:

Maybe someday we can stand together

Not afraid of what we see

Maybe someday understand them better

The weird things inside of me.

Whether or not we understood them better by the end of night, the weird things inside of David Byrne and St. Vincent put on quite a show. I’m not sure how often audiences get up and dance in their seats at the Beacon but it happened this night. Adding an extra layer of resonance to it all were the weird things inside the Beacon Theatre, a building no doubt inspired by the 1893 Chicago Exposition and the White City, a dizzying assemblage of neoclassical cityscapes and midway attractions that gave physical form to Whitman’s ideal. You could hardly find a more appropriate setting for David Byrne and St. Vincent’s songs—a musical world populated by a cast of all-American eccentrics (including themselves) and fascinated with spectatorship, whether watching TV or simply watching life go by.

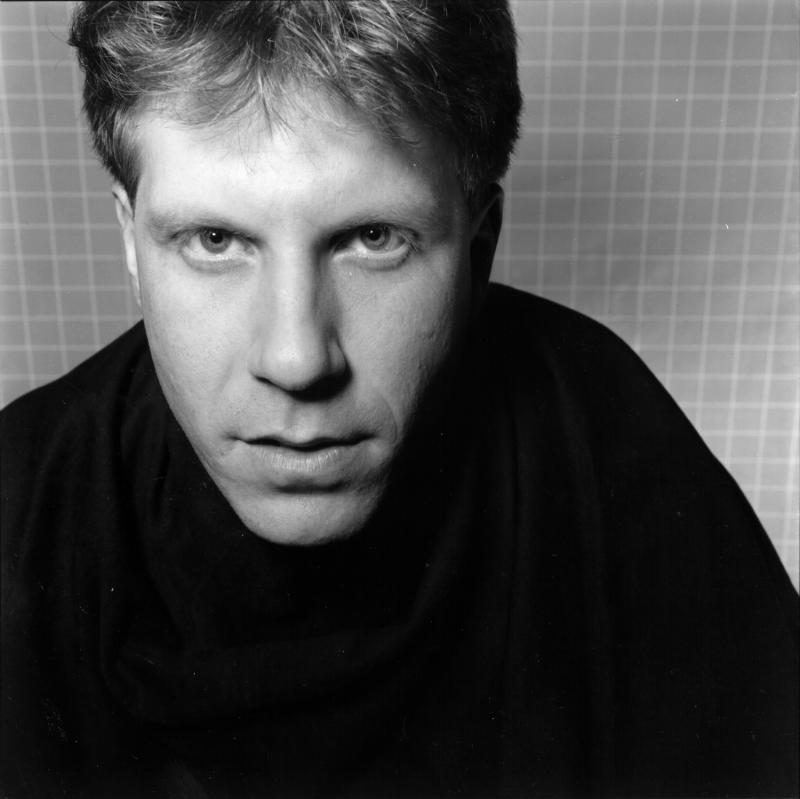

Jason Lee Oakes studied ethnomusicology at Columbia University and now teaches at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. His blog on music in the 2012 presidential race can be read here.