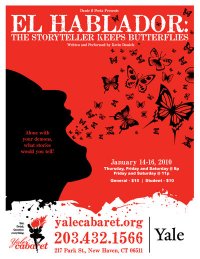

Kevin Daniels’ oneman show, El Hablador: the Storyteller keeps butterflies, ending its 3-day run tonight at the Yale Cabaret, involves several conceits that blend together to create a unique theatrical experience. First of all, “el hablador” (the storyteller) features the notion that the main character -- Daniels, a young black man in a suit, barefoot -- is stranded on an island where his need to tell stories is fulfilled by messages in bottles. These hang from the ceiling, and the storyteller selects one or another, seemingly at random, and offers it with friendly gestures to an audience member who then reads aloud the message inside. Addressed to the storyteller, the messages present occasions for a story.

Another conceit comes into play through the storyteller’s name: Dante, an illusion to the famous poet who catalogued the inhabitants of hell in its various circles. Indeed, the stories El Hablador tells dramatize social hells of our contemporary world for four protagonists in interrelated stories.

Yet another conceit could be said to be the form of the stories themselves: delivered in highly rhythmical, allusive, visceral raps, the stories are offered as spoken both by and about the character in question. The most effective, to my mind, was the tale of an African-American father trying to flee the crisis of Hurricane Katrina with his family; the story provided a convincing sense of other characters in the man’s life, as voices or ghosts pursuing him from the disaster. The story of a young man trying to articulate his relation to his own sexuality was deft in its use of dramatic, confrontational soliloquy. The other stories, of an Hispanic drug-dealer victimized by the ‘no exit’ like space of his ghetto upbringing, and of his white former girlfriend who moved to Vegas to become a stripper, while full, like all four monologues, of wonderful verbal riffing and expressive outbursts that were almost show-stopping in their brilliance, seemed to trade more on certain cliches of ‘the life’ than the other two monologues did.

Still another conceit that was perhaps the most striking was that the storyteller -- who was a childlike, ingratiating mime-figure when speaking in his native language -- ‘became’ the character in the monologue as if possessed by the voice, or as if he were a machine into which the ‘track’ had been inserted. This was signaled by the breakdowns into repetitions and slowing speed as monologues drew to an end. It was an effective transition device which, because of Daniel’s precise sense of rhythm -- matching physical and verbal contortions in expressive combination -- never seemed forced. Rather it was unnerving each time, as if watching a puppet with Tourette’s Syndrome crash under the calamitous force of having to articulate such passionate, victimized lives.

Not being someone for whom rap has had much allure, I have to say that Daniels' monologues impressed me with the scale to which the form can be stretched, combining the strengths of spoken word poetry, with allusions and metaphors piling up quickly, of dramatic monologue, in which a true self is revealed by choice of expression, and of oral storytelling, in which choice of incident and detail gives reality to scenes we “see” only in words.

El Hablador provides a commanding performance and gripping theater. The space of the Cabaret was very effectively used through placement of the action, lighting the space to include the audience readers, and the scenic quality of hanging bottles like stars in the sky, each a story.

Saturday, Jan 16 @ 8 and 11pm:

http://www.yalecabaret.org/home.php

Pop!, the new musical now playing in its world premiere at the Yale Rep, could have been a camp classic: staging a song-and-dance extravaganza on the shooting of famed pop artist, provocateur, and blasé icon Andy Warhol at the hands of a disaffected feminist revolutionary, Valerie Solanis, in 1968. The silver Factory, Warhol’s headquarters at 231 East 47th street in NY, was famed for its stable of hangers-on, including “poor little rich girl” Edie Sedgwick, pre-op transexual Candy Darling, and other would-be geniuses. From this remove, it would be possible to play these characters for laughs, as a collective disgorging of whatever is stored in the closet marked “NYC Underground c. 1967.” Along the way, we might be amused (or not) by the fact that one of these “superstars” had the wherewithal to shoot and critically wound The Master.

Pop!, the new musical now playing in its world premiere at the Yale Rep, could have been a camp classic: staging a song-and-dance extravaganza on the shooting of famed pop artist, provocateur, and blasé icon Andy Warhol at the hands of a disaffected feminist revolutionary, Valerie Solanis, in 1968. The silver Factory, Warhol’s headquarters at 231 East 47th street in NY, was famed for its stable of hangers-on, including “poor little rich girl” Edie Sedgwick, pre-op transexual Candy Darling, and other would-be geniuses. From this remove, it would be possible to play these characters for laughs, as a collective disgorging of whatever is stored in the closet marked “NYC Underground c. 1967.” Along the way, we might be amused (or not) by the fact that one of these “superstars” had the wherewithal to shoot and critically wound The Master.