Review of El Huracán, Yale Repertory Theatre

The opening scene of Charise Castro Smith’s El Huracán, now in its world premiere at Yale Repertory Theatre, is literally magical. A young woman in an elegant dress performs magic tricks on a circular stage, aided by a male partner in a tux. The swankiness of the act—set in the celebrated Tropicana nightclub in pre-Castro Cuba—is abetted by the dance the couple, Valeria (Irene Sofia Lucio) and Alonso (Arturo Soria), perform to Frank Sinatra’s “Come Fly With Me.” It’s suave and nostalgic and at a remove from the realities of the play, and for a little while we get to bask in a rare kind of show-biz transcendence.

Young Valeria (Irene Sofia Lucio), Young Alonso (Arturo Soria) (photographs by T. Charles Erickson)

Looking on with us is Valeria (Adriana Sevahn Nichols), now a woman in her eighties. We soon learn that her current world—Miami—is under threat by Andrew, the impending category 5 hurricane that caused death and major damage in 1992, and by advanced Alzheimer’s. Smith’s play dramatizes the way the past is made precarious by our memory and the playwright uses the cataclysms that repeatedly strike the region to signal the precariousness of its inhabitants’ present and future. (As I write this, Michael, a category 2 hurricane, is set to strike the gulf.)

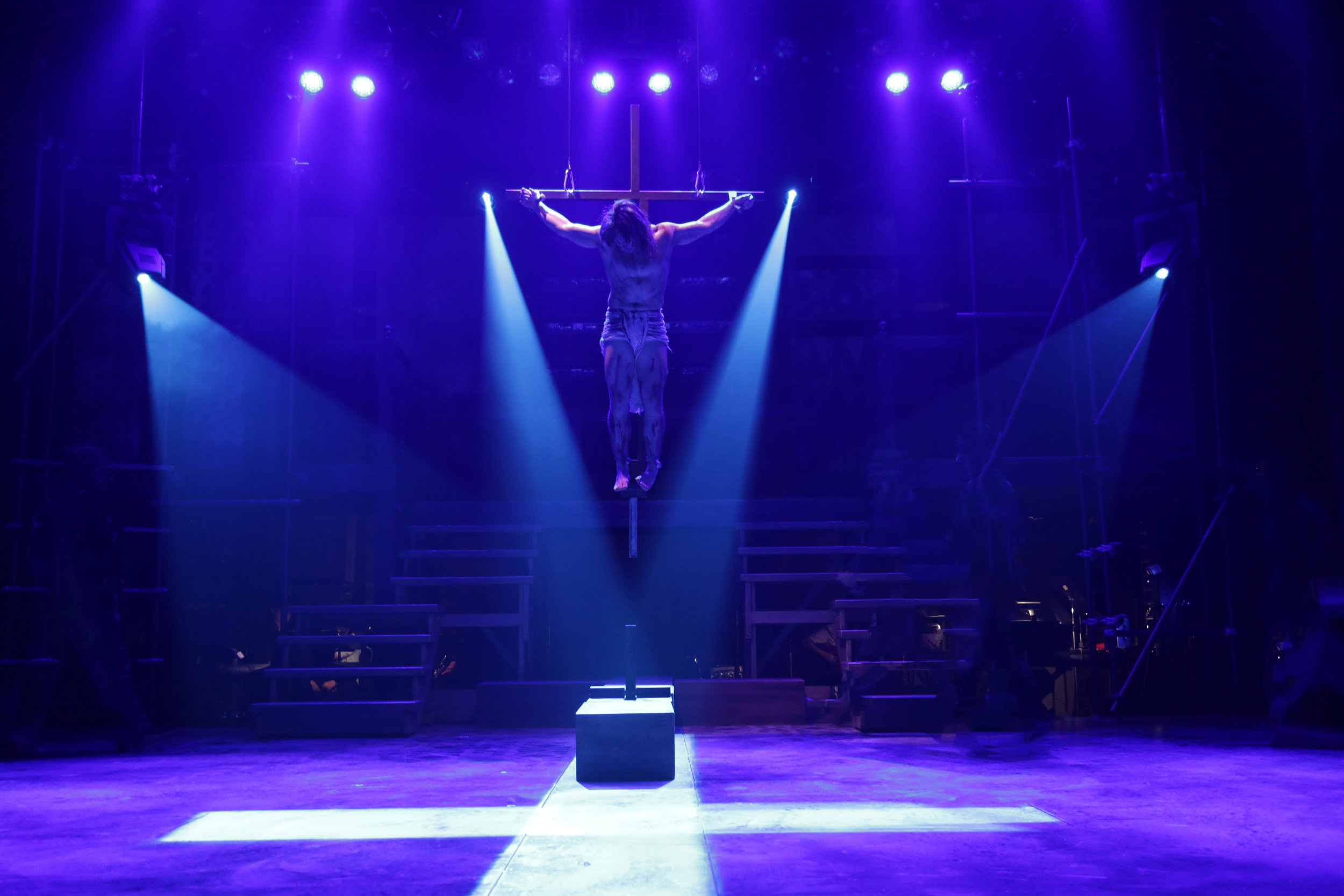

Directed by Laurie Woolery, who showed a similarly useful grasp of the amorphous for Imogen Says Nothing at Yale Rep last year, El Huracán is a kind of dream or memory play. Its action takes place in different times, amplified by the memories that beset Valeria, and made lyrical by Yaara Bar’s beautiful projections, acts of legerdemain (Christopher Rose, Magic Designer), and a striking set by Gerardo Díaz Sánchez. The staging is consistently interesting, keeping us off-guard, never sure where the story is going or how events will be manifested.

Valeria (Adriana Sevahn Nichols)

Valeria is barely aware of her surroundings most of the time and mistakes her granddaughter Miranda (Irene Sofia Lucio) for an assistant, while her daughter Ximena (Maria-Christina Oliveras) has to play parent to both her own mother and her daughter. Miranda—a rather immature doctoral candidate who seems more like an undergrad—is back home in Miami to help defend the homestead from Andrew. She’s aided by Fernando, a local mensch helping out her abuela. A flirtatious scene between Fernando and Miranda helps to focus us on the action, which otherwise—but for effective special effects to signal the hurricane—tends to be elusive.

It’s clear that Valeria is more apt to be talking to her sister Alicia (Jennifer Paredes) on the beach, back when they were girls together and having their first flares of male interest, than to be conscious of what her daughter and granddaughter want of her. But the past barely congeals, despite some very diverting projections of Alicia swimming. The courtship between Alonso and Valeria is mostly pro-forma, whereas little moments, like Fernando appreciating Miranda’s butt when she’s on a ladder, or both Miranda and Valeria appreciating Fernando’s physique when he removes his shirt, help us experience the tactile qualities of the 1992 setting.

Fernando (Arturo Soria), Miranda (Irene Sofia Lucio)

With the past in Cuba vague—as presented in a simultaneous English and Spanish rendering by Valeria and Alonso (Jonathan Nichols) respectively—the main action takes shape around the youngsters, until an unfortunate occurrence brings home the perils of the present. We’ve barely had time to digest that before Smith’s plot flings the action into 2019 in the aftermath of a category 6 storm that devastates Miami. By then, Ximena is elderly and Miranda middle-aged. Indeed, the years are imposed upon them by a costume-change, complete with padding, that occurs onstage about midway through the play.

In 2019, Miranda is back in Miami to help Ximena, now suffering from the same memory-devastating malady that beset her own mother, and to seek forgiveness for an awful “accident” that happened in 1992. Again, a young male is on hand to help (Arturo Soria, engaging in each incarnation), though Theo is a relative and a Cubano trying to learn English, to be matched with Val (Jennifer Paredes), Ximena’s granddaughter, who speaks Spanish straight out of a school primer. The scenes of Miranda, a bit professorial now, trying to take care of Ximena, who is even less sympathetic toward her daughter than when both were much younger, don’t do much for either character, though Ximena gets a poetic speech about the mother she’s trying to remember.

Ximena (Maria-Christina Oliveras), Valeria (Adriana Sevahn Nichols)

There’s a strange disconnect at the heart of the play as it tries to find a way to evince both the devastation of the hurricane, where special effects can help, and the elusiveness of memory, where a deliberate porousness between eras and identities, decorated with a smattering of Shakespearean references, can only do so much. Smith’s play is highly suggestive in its setting and staging, but not quite convincing in terms of the particular characters who live through its changes.

As the aged Valeria, Adriana Sevahn Nichols is charming and somewhat mysterious, playing well the youthfulness of Valeria in her own mind. As Ximena, who we see go from fretful caretaker of Valeria and castigator of Miranda to fretful elder and castigator of Miranda, Maria-Christina Oliveras registers the changes in the family dynamic gracefully. As Miranda, Irene Sofia Lucio is best when flirtatious and youthful—chastened and regretful seems not to become her. As Young Valeria, her prestidigitation is impressive. Jennifer Paredes is brightly active as Alicia, and she brings the right note of earnest maturity to Val, the college student of 2019. As the aged Arturo, Jonathan Nichols handles well the best scene between Arturo and Valeria, where we learn how things ended up. And, as Young Alonso, Fernando, and Theo, Arturo Soria gets to show off his moves, his smile, his bod, his Spanish and to be an asset in every scene he’s in.

El Huracán can best be seen as an intergenerational love story, where the love is for family, Cuba, Florida, and other threatened areas, and where the generations are formulated as: a past long gone, a fitful present apt to fail its elders, and a future where, if there’s any hope, it’s in the young. It’s also a revisiting of the Tempest where the magician Valeria, unlike Prospero, can’t control the storms to come, nor when the book of the brain will be drowned.

El Huracán

By Charise Castro Smith

Directed by Laurie Woolery

Choreographer: Angharad Davies; Scenic Designer: Gerardo Díaz Sánchez; Costume Designer: Herin Kaputkin; Lighting Designer: Nic Vincent; Sound Designer: Megumi Katayama; Projection Designer: Yaara Bar; Magic Designer: Christopher Rose; Puppet Designer: James Ortiz; Production Dramaturg: Amauta M. Firmino; Technical Director: Alex Worthington; Dialect Coach: Cynthia DeCure; Fight Director: Rick Sordelet; Stage Manager: Christina Fontana

Cast: Irene Sofia Lucio, Jonathan Nichols, Maria-Christina Oliveras, Jennifer Paredes, Adriana Sevahn Nichols, Arturo Soria

Yale Repertory Theatre

In collaboration with The Sol Project

September 29-October 20, 2018