Review of Laughs in Spanish, Hartford Stage

Alexis Scheer’s Laughs in Spanish, playing at Hartford Stage through March 30, grabs us from the start: a blank wall where expensive artworks should be hanging and a loud, sustained scream of “fuuuuuck!” from art dealer Mariana (Stephanie Machado). ‘Tis the season of the famed Art Basel Miami Beach, and Mariana must needs sell art. The missing paintings, though, come to seem mostly a minor plot point, a way to start the action with a bit of bait-and-switch. Directed by Lisa Portes, the play begins with comic, on-the-job high anxiety, but gradually becomes a play about relationships, and family, and community values.

I might have preferred to watch Mariana deal with the art world.

Mariana (Stephanie Machado), Estella (Maggie Bofill) in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

But that’s just me: the accent here is on the accents, we might say. The play treats—with ready humor and a bubbly cast of characters—the shifting roles people play in their lives—work, family, romance—and, more particularly, the tonal shifts that come from being manifestly Latine, in some situations, and more knowingly Angloese in others. The fun of watching the play comes in seeing how the role and tone shifts are instinctive, instructive, and played for effect in a variety of social situations by this able cast.

Start with our screaming art dealer (Machado a little later does a rattled scream that easily eclipses her opening bellow): Mariana, we see, is a savvy, self-sustaining success, but success can easily totter into failure; besides the upcoming reception for art now gone, she has to deal with her assistant Carolina (María Victoria Martínez) who is a Latine artist looking for a break—and who cooly suggests her works should be hung in lieu of the purloined pieces; then there’s Mariana’s mom, Estella (Maggie Bofill), who is a celebrity because of a role she plays in a telenovela, and who is back in her old Wynwood stomping grounds for reasons of her own (but which are relevant to Mariana). Coincidentally, Jenny, Estella’s assistant, an Anglo, is a former school-chum of Mariana’s at the boarding school that absentee mom Estella sent her young daughter to. Does that backstory spell friction or romance? Meanwhile, there’s also very agreeable Juan (Luis Vega), the kind of security guard who thinks it’s no sweat when highly valuable art disappears on his watch, and who is more than cozy with Carolina.

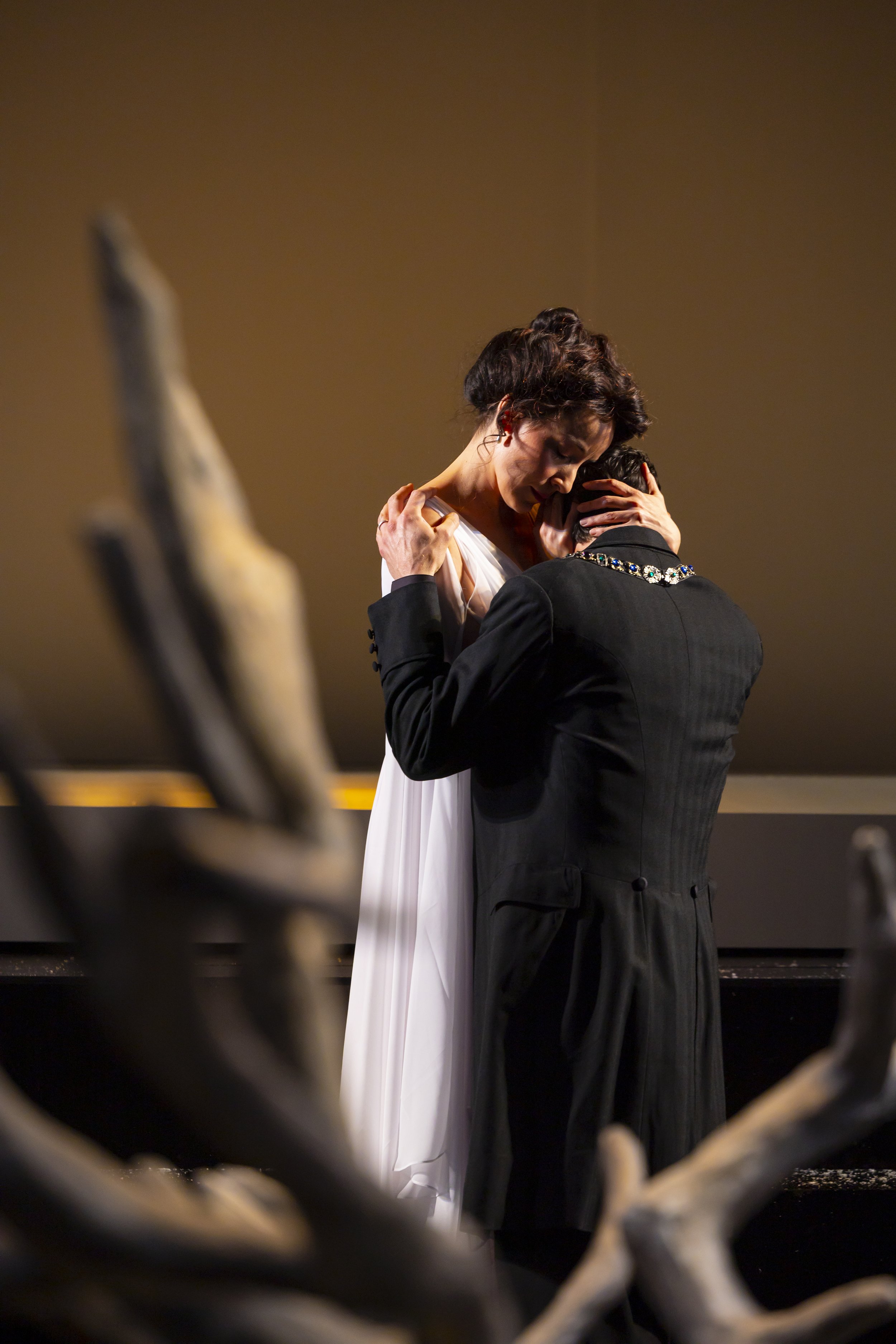

In other words, there are past, present, and future situations aplenty. In all the busyness of the various cross-purposes, the play loses some of the charm that got us interested in the first place. The two strong characters here are Mariana and Estella, both given fascinatingly varied readings by Stephanie Machado and Maggie Bofill, respectively. The mother-daughter dynamic is the most fully fleshed-out, and watching these two work through their pasts and presents is rewarding viewing. Bofill’s Estella is the more demanding and commanding, even when she tries to be humble, and her range of ways to work a room never runs dry. Late in the play she delivers a speech/monologue that left me a little uncertain of its relevance but never in doubt that it was fun to listen to and watch.

Estella (Maggie Bofill); Mariana (Stephanie Machado), foreground, in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

Machado’s Mariana can be breezy, ballsy, bitter, blithe—and believably girlish. She’s comes across as the kind of character that—if maybe not telenovela material—can be easily imagined as a sit-com heroine, cut from the Mary Tyler Moore Show mold (if that’s not too ancient a reference). This week, we see her deal with missing art, a school crush, and the fall-out from mom’s misdemeanors. Next week?

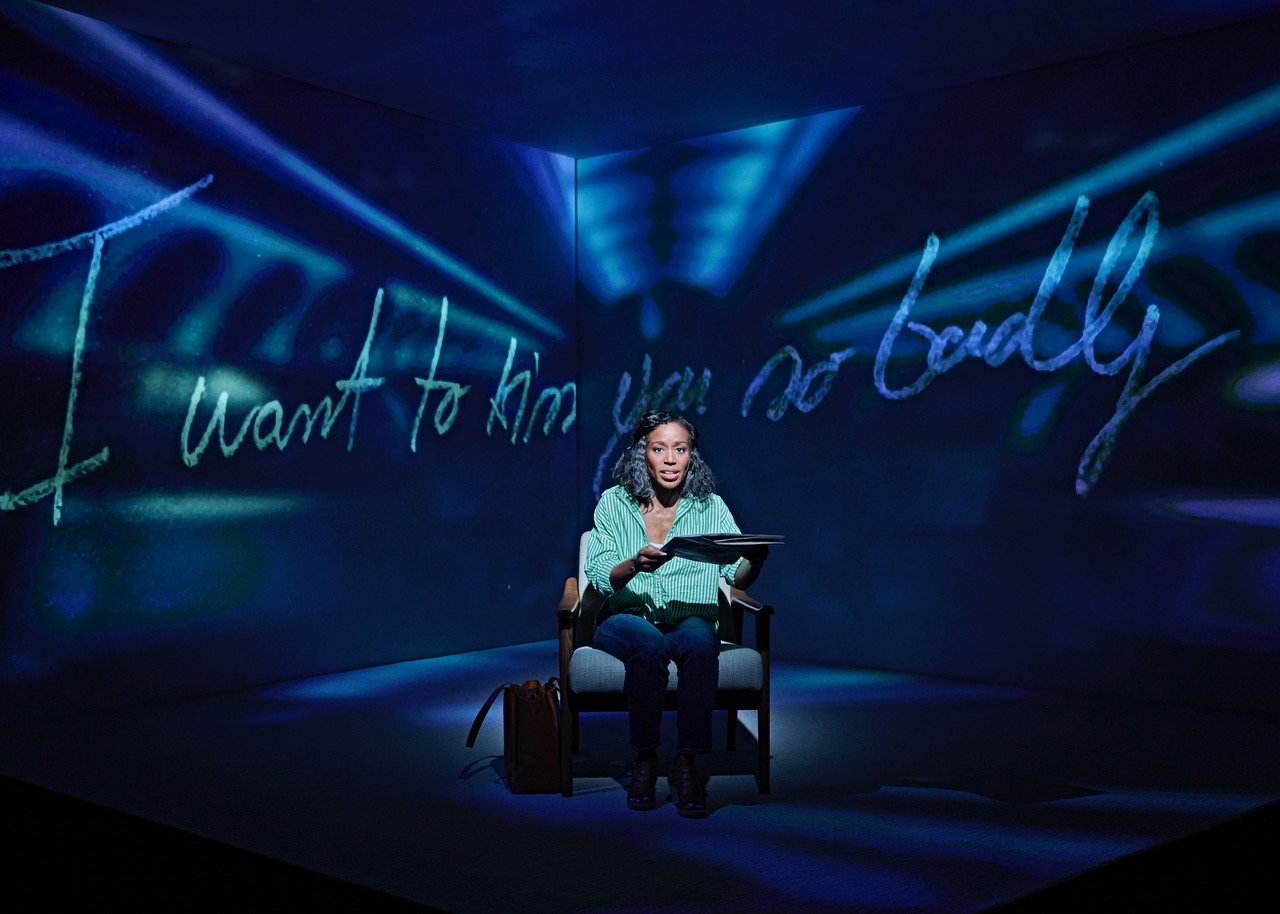

Jenny (Olivia Hebert), Mariana (Stephanie Machado) in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

The supporting cast all get to have spotlight moments too: the scene of Carolina and Juan in his car with siren and lights going works as contemporary comedy-romance; Jenny’s scene with Mariana lingers maybe a bit too long in the indirection of romantic buildup but is still sweet; and anyone’s scene with Estella upgrades the play’s humor. She’s a walking, talking comic melodrama.

Estella (Maggie Bofill) in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

Brian Sidney Bembridge’s scenic design is a bright open space that also shows off Hartford Stage’s spinning stage, so that we get a welcome scene change—twice—in the midst of the action. The street-art on a wall has the requisite Miami feel, I assume, and the forest of trees is foreboding and funky at once. Harry Nadal’s costumes are colorfully varied, and there are lively dance/movement routines to the original music by Daniela Hart/UptownWorks. Throughout, Lisa Portes shows a sharp sense of how to have her cast play to an appreciative audience. Most laughs land and some even simmer.

Carolina (Maria Victoria Martínez), Juan (Luis Vega) in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

Laughs in Spanish shows us a vividly turning wheel that presents each character functioning in more than one environment and in more than one capacity. The point of it all, ultimately, turns on which self each character is most comfortable as; or we might say, which identity is the most authentic. The strength of Scheer’s play is that it shows we are each authentically, truthfully, actually more than one thing. The best we can do is make our various selves align with those we care about most.

Mariana (Stephanie Machado), Estella (Maggie Bofill) in Laughs in Spanish at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

Laughs in Spanish

By Alexis Scheer

Directed by Lisa Portes

Scenic Design: Brian Sidney Bembridge; Costume Design: Harry Nadal; Lighting Design: Sherrice Mojgani; Original Music & Sound Design: Daniela Hart/UptownWorks; Dialect & Voice Coach: Cynthia Santos DeCure; Production Stage Manager: Theresa Stark; Assistant Stage Manager: Christina M. Woolard; Associate Artistic Director: Zoë Golub-Sass; Director of Production: Bryan T. Holcombe; General Manager: Emily Van Scoy

Cast: Maggie Bofill, Olivia Hebert, Stephanie Machado, Maria Victoria Martínez, Luis Vega

Hartford Stage

March 6-30, 2025