Review of Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous, Hartford Stage

Hartford Stage has a stable tradition of offering literate plays handsomely mounted, and the current production, Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous by Atlanta-based playwright Pearl Cleage, directed by Susan V. Booth, lives up to that expectation. What’s more, as a plus for theater fans, the play’s story centers on feminine—and feminist—expression and generational rivalry in the theater. It opens with a deliberate quotation of a Bette Davis movie line (previously lifted by Edward Albee) and then kind of reverses the situation of All About Eve (one of Davis’ landmark roles) so that, here, the up-and-comer proves more sympathetic than the great actress. And the cast of four engaging African American women bring it—with laughs to spare.

Seated: Anna (Terry Burrell), “Pete” (Shakirah Demesier); standing: Betty (Marva Hicks), Kate (Cynthia D. Barker) in Hartford Stage’s production of Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous; photo by T. Charles Erickson

The basic situation: Anna Campbell (Terry Burrell) has become a grand dame of classic theater, noted for roles like Medea and Hedda Gabler, but she’s been living in Europe due to the outraged reception of her notorious one-woman show back in the ‘90s. Dubbed “Naked Wilson,” the show featured Campbell, in the nude, reciting famous speeches from August Wilson plays, speeches all written for African American male characters. The implied criticism: Wilson, for all his greatness, downplayed the importance of women in his dramas and in Af Am cultural life in general. Now, a theater festival in Atlanta, organized by Kate Hughes (Cynthia D. Barker), an energetic young producer, wants to revive “Naked Wilson” and give Campbell an honorary award.

All well and good—except Campbell assumes this is her chance to give a farewell performance of her signature play, while at the same time claiming nudity as something that doesn’t only encompass younger women. Hughes, however, has hired a young “performance artist” (actually more of a stripper and pornographic movie actress) “Pete” Watson (Shakirah Demesier) to perform “Naked Wilson” nude, though Watson isn’t exactly versed in dramatic monologues nor Wilson’s plays. A further key role in Cleage’s play, that of Betty Sampson, Campbell’s assistant and companion, is provided by Marva Hicks who is able to hang fire and comment, both verbally and silently, to great effect.

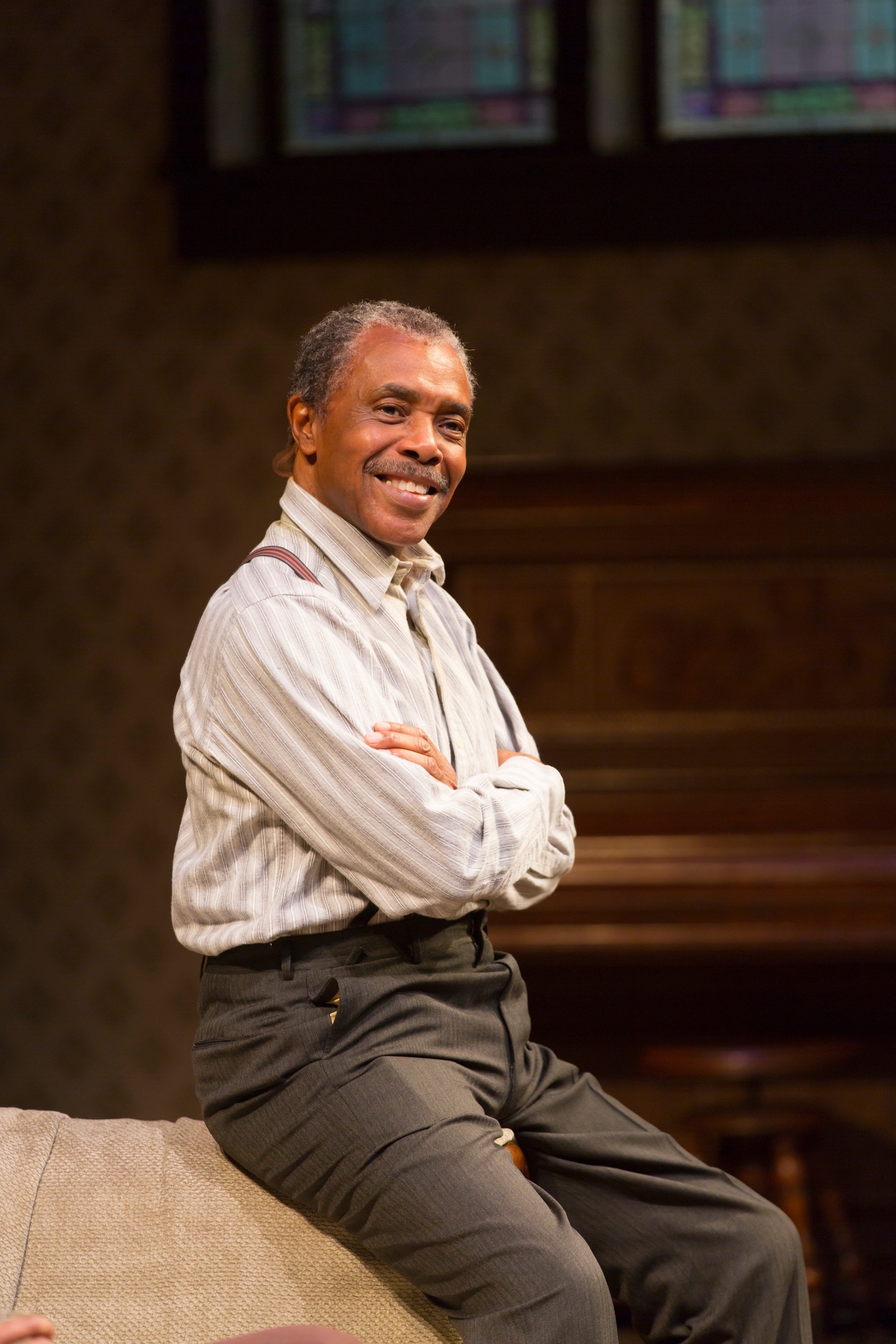

Marva Hicks as Betty Sampson in the Hartford Stage production of Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous; photo by T. Charles Erickson

The plot of Cleage’s play, then, is essentially a sit-com: how to disabuse Campbell of her mistake without alienating her, and how to finesse what is bound to be a culture-clash between a diva of the theater and a demoiselle of the skin trade. Cleage beefs up the basic comic premise with some very tangible issues, most having to do with how one generation copes with the next.

At the heart of the play is the question: “must we eat our young?” It’s a way of depicting the tendency of those now able to rest on their laurels to undermine the tastes, talents and prestige of those still trying to make a name. That situation, we might say, is perennial; no matter how much the up-and-coming generation resents the suppressions foisted on them by their elders, they will almost certainly behave similarly once they become elders.

By taking on the plays and reputation of August Wilson, even if with admiration tinged with a certain comic deflation, Cleage adds a further dimension to the play’s intergenerational struggle. Wilson was the dominant African American playwright of the 1990s and in some ways still is. In the past decade (during which I’ve reviewed theater in Connecticut), his plays have been on offer most seasons and I’ve seen them at Hartford Stage, Long Wharf Theatre, and of course, Yale Repertory Theatre, where a number of them had their debuts. He is a grand old man of American theater and yet—unlike some others, such as Tennessee Williams or Eugene O’Neill—his female roles tend to be much slighter. Thus Campbell’s protest play is a point well-taken, for not only do female actors get short-changed in Wilson’s plays, arguably, but—with strict gender distinctions in casting—female actors never get to deliver the speeches Campbell performed in her piece.

In choosing a performer such as “Pete” (her given name, Precious, already sounded like a stripper name, to her, so she went for something apposite), Hughes opens the door to performance beyond the bounds of classic theater. Certainly, such was implied in Campbell’s use of nudity as an avant-garde gesture intended to break through certain stodgy assumptions about theater, but, Campbell claims, the real point was hearing a very capable actress deliver Wilson’s lines. Hughes could’ve gotten a worshipful stage-actress understudy-type to take on “Naked Wilson” but chose instead a woman with some of the same “stop-at-nothing” fire Campbell once had. As Campbell, Burrell makes us believe in both the greatness of her skills and the wearying anxieties of having to carry on past her “day.” And Demesier’s Watson has the nonchalance of whatever is “now.”

Terry Burrell as Anna Campbell and Shakirah Demesier as Precious “Pete” Watson in The Hartford Stage production of Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous; photo by T. Charles Erickson

The best parts of the play come when Campbell and Watson are finally face-to-face. In fact, there’s a bit of a lull after the initial setup of the situation that could be mitigated by quicker pacing (but, given that the play comes in at about 100 minutes, it’s not as if it drags). Watson is the kind of performer who baulks at nothing and has the confidence that comes from “clicks” (or internet attention) rather than the traditional gatekeepers of artistic success. Campbell, increasingly insecure in this new world, still knows what she knows: great theater isn’t made by amateurs. A resolution, if it’s to come, will have to allow both sides of the generational divide to respect and appreciate the other. And the terms of that rapprochement are what make this play signify. What’s more, Hicks—as the true elder here—gets to steal the show with a concluding song and comment that’s “just showing off” very gamely indeed.

Warmly entertaining with some jabs and bristles, Angry, Raucous and Shamelessly Gorgeous is funny, not mawkish, and happily gorgeous: the $500-per-night suite where Campbell and Sampson hang out is quite a spread, in Collette Pollard’s design, and Kara Harmon’s costumes are all very becoming, especially the knock-out red number “Pete” sports during a believably “gone viral” moment late in the play. If, in the end, Cleage’s play plays to our classic theater preferences over the grittier, more showy aspects of today’s entertainment culture, well, that’s what Hartford Stage audiences are there for.

The cast of Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous at Hartford Stage; photo by T. Charles Erickson

Angry, Raucous & Shamelessly Gorgeous

By Pearl Cleage

Directed by Susan V. Booth

Scenic Design: Collette Pollard; Costume Design: Kara Harmon; Lighting Design: Michelle Habeck; Sound Design: Clay Benning; Wig Design: Lindsey Ewing; Production Stage Manager: Anna Baranski; Assistant Stage Manager: Samantha Honeycutt

Cast: Cynthia D. Barker, Terry Burrell, Shakirah Demesier, Marva Hicks

Hartford Stage

January 13-February 6, 2022