Review of Detroit ’67, Hartford Stage

In the summer of 1967, the city of Detroit exploded. There was looting and arson in black neighborhoods, where the racist treatment by the police incensed the residents into violence. The police, and eventually the National Guard and U.S. Army, retaliated. The rebellion played out over five days as the most destructive riot of the many that occurred that summer, and one of the worst in U.S. history.

Halfway through Dominque Morisseau’s Detroit ’67, playing through March 10 at Hartford Stage, directed by Jade King Carroll, the chaos in the streets starts and impinges on the story. At that point, the play, concerned with a drama of personalities, is set against a threatening background that will likely lead to death. If the role of the offstage violence in the play seems a bit convenient, its presence makes clear the kind of underground life these characters live, the risks they face, and the resentments below the surface.

Chelle (Myxolydia Tyler) in Hartford Stage’s production of Detroit ‘67 (photos by T. Charles Erickson)

Set entirely in the basement of the house Chelle (Myxolydia Tyler) and Lank (Johnny Ramey), short for Langston as in Hughes, grew up in, the action, initially, concerns the siblings’ efforts to earn money by hosting afterhours parties in the basement. To that end, Lank, contrary to his sister’s devotion to vinyl, has procured a new-fangled device: an 8-track player! Such details take us back to a different time, greatly aided by Dede M. Ayite’s period costumes and Leah J. Loukas’ hair and makeup design. The feeling of a bygone era is key to the play, recreating a world in which the greats of Motown—Martha & the Vandellas, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, the Temptations, the Four Tops—are at the top of their game. As a defining export from black Detroit also beloved of white America, Motown was an important cultural ambassador, a fact which makes the hostility in the streets all the more searing.

Bunny (Nyahale Allie)

The long shadow of that era in popular culture means we feel we know these characters and how they interact. They’re familiar, whether it’s the clash between the siblings over how to spend their inheritance from their deceased parents—Lank wants to invest in opening his own club, Chelle is skeptical—or Lank’s smooth-talking buddy and would-be business partner Sly (Will Cobbs), who may be sweet on Chelle, or Chelle’s sassy and brassy friend Bunny (Nyahale Allie) who has “a lot to go-around.” Into this mix, even before we get to the riots, enters Caroline (Ginna Le Vine), a white girl in a go-go outfit whom Lank can’t help helping when he finds her wandering dazed, bloodied, and bruised in traffic.

Caroline (Ginna Le Vine)

Now we’ve got the makings for interracial romance, and that might be enough of a vehicle for revisiting the way black and white cultures didn’t cross lines much during those times. That they might and did was part of the thrill and risk when the races mixed, and Le Vine and Ramey do a good job of playing with a fire set on a low heat. It could catch, but there are many complications, not least Chelle’s aversion to Caroline—though she lets her stay and help with serving in the basement club—and Lank’s unease about going behind his sister’s back to buy a real club that’s up for sale.

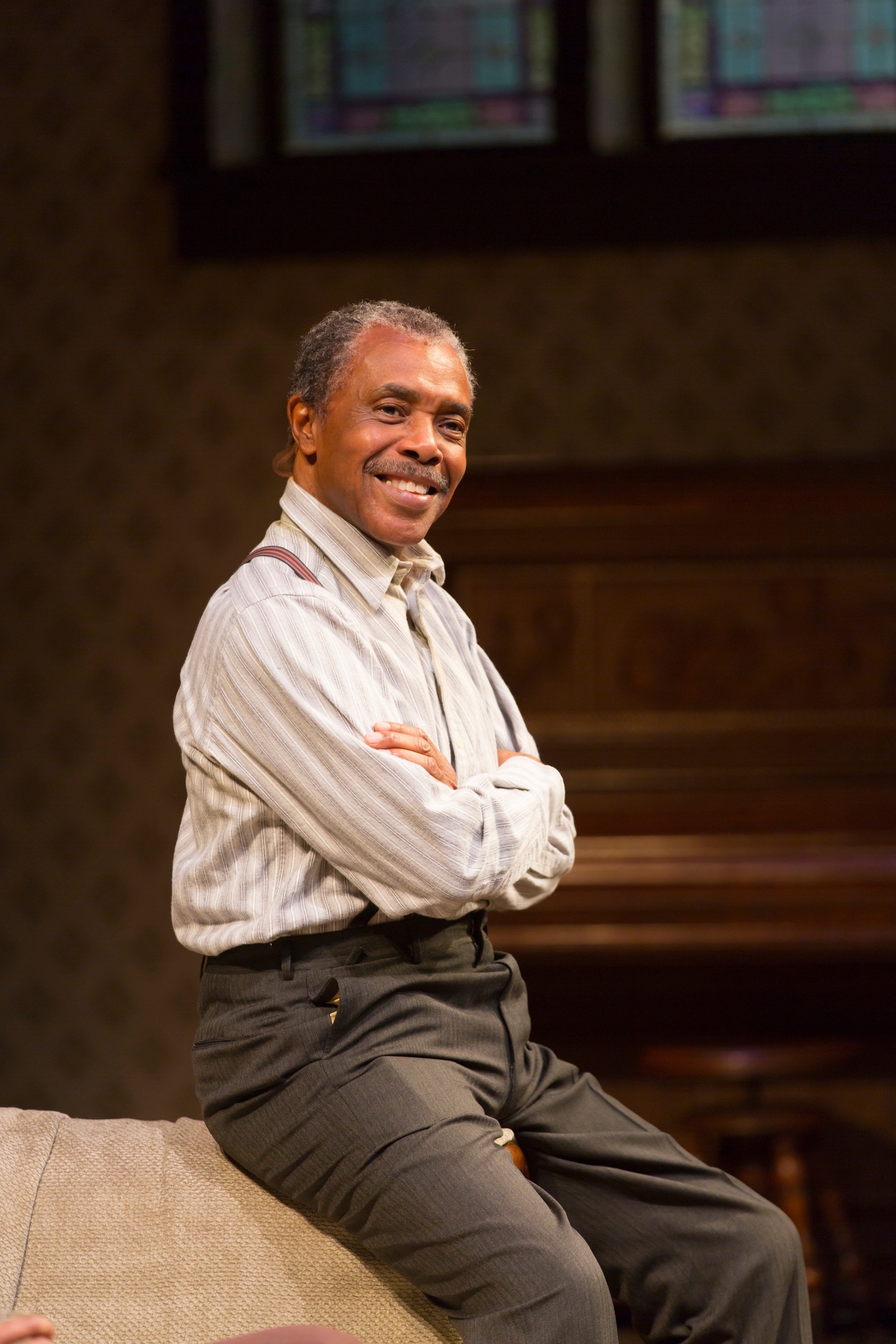

Sly (Will Cobb), Lank (Johnny Ramey)

Director Carroll is skilled with a play that has a lot of episodic encounters, its characters chatting and sometimes grooving to the tunes, while having little moments of discontent or disagreement. The pacing, for a play that runs to two and a half hours, is nearly flawless. And, while we can feel the plot like a net closing in, there are many nice touches that keep our disbelief suspended. Not least is what strikes me as the heart of what Morisseau is getting at: a plaintive grievance that Chelle sounds to Bunny about what she sees as a kind of betrayal in Lank’s interest in Caroline. And that means that Lank is apt to fail his sister where it counts.

Chelle (Myxolydia Tyler), Lank (Johnny Ramey)

At the heart of the play, then, is Chelle, and Myxolydia Tyler lets us hear her, not least in a gripping moment when the seductive power of “Reach Out I’ll Be There” reaches catharsis. Cobbs, groomed to look perfectly the part, is suitably sly and sexy as Sly, and Allie’s Bunny offers both comic relief and canny appraisal of the others, the kind of friend you want on your side.

Chelle (Myxolydia Tyler), Sly (Will Cobbs)

The further plot elements—the vulnerability of the club during the disturbances, Caroline’s ties to corrupt cops, the doomed love aspects—begin to pile up as though Morisseau can’t resist reaching out, trying to bring in all the possible obstacles and upsets the time and place afford. If there were less story, there might be more time for the characters to complicate the roles they’ve been written into.

Bunny (Nyahale Allie), Chelle (Myxolydia Tyler)

An ambitious, at times meandering play, Detroit ’67 works at Hartford Stage in Carroll’s capable way with a capable cast, each contributing to an engaging ensemble. Like the five-part vocals of a song by The Temptations, Detroit ’67 gives each voice its space.

Detroit ‘67

By Dominique Morisseau

Directed by Jade King Carroll

Scenic Design: Riccardo Hernandez; Costume Design: Dede M. Ayite; Lighting Design: Nicole Pearce; Sound Design: Karin Graybash; Hair & Makeup Design: Leah J. Loukas; Fight Director: Greg Webster; Vocal Coach: Robert H. Davis; Production Stage Manager: Heather Klein; Assistant Stage Manager: Nicole Wiegert; Production Manager: Bryan T. Holcombe; General Manager: Emily Van Scoy; Associate Artistic Director: Elizabeth Williamson

Cast: Nyahale Allie, Will Cobbs, Ginna Le Vine, Johnny Ramey, Myxolydia Tyler

Hartford Stage

February 14-March 10, 2019