Review of Skeleton Crew, Westport Country Playhouse

Skeleton Crew is the third play from Dominique Morisseau’s The Detroit Project to be staged in Connecticut this season; it’s also the most recently written and the best of the three. Like Paradise Blue (at Long Wharf in the fall), and Detroit ’67 (at Hartford Stage in the winter), this four-person play is set in a very particular place—Detroit, of course—and time: in this case, the years of the Great Recession of the twenty-first century. That was the “too big to fail” era when the big automakers in Detroit declared bankruptcy, followed by the city itself shortly after.

Set entirely in an automotive plant’s very realistic breakroom (by Caite Hevner), Skeleton Crew lets us into the situation with a fly-on-the-wall access. We see how those who turn up for work each day have their frictions, their flirtations, their agreements and disagreements. And bit by bit we gain insight into what’s at stake in these lives, even as the characters themselves begin to realize how tied they are to a certain way of life, now under threat, and to each other.

Shanita (Toni Martin), Dez (Leland Fowler), Faye (Perri Gaffney) in Westport Country Playhouse’s production of Skeleton Crew (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Faye (Perri Gaffney) is the wise elder who has put in twenty-nine years on the factory floor—but not thirty. The remaining year is necessary for full benefits at retirement. She’s canny, at times jokey towards the others, and opens the play lighting up a cigarette in front of a No Smoking sign. The sign is an indication of how things are changing: more and more effort is being made to make workers behave by the rules, so that those with infractions—for smoking on site, lateness, gambling—can be dismissed. Faye knows times are tough—soon we learn just how tough—and is barely hanging on. Gaffney plays Faye without overt sentimentality, letting us admire her and her philosophic grasp of realities.

The most likely candidate for downsizing is Dez (Leland Fowler) who is too young to kowtow easily to authority and who has dreams of starting his own business—he needs to hang on until he’s got the start-up money. Shanita (Toni Martin), the star of the assembly line, is pregnant, very particular about her salad dressing, and apt to blame her mood swings on her hormones. She fields what might be pro forma come-ons from Dez with grudging patience. The arc of these two actually taking an interest in each other is developed slowly and without coy pretense. The two actors’ command of Morisseau’s language, which captures very subtle registers of emotion with skill, is fully engaging. A joy of the show is how naturally the dialogue flows, letting talk be the medium by which the characters move from rote reactions to something deeper.

Shanita (Toni Martin), Dez (Leland Fowler) (photo by Carol Rosegg)

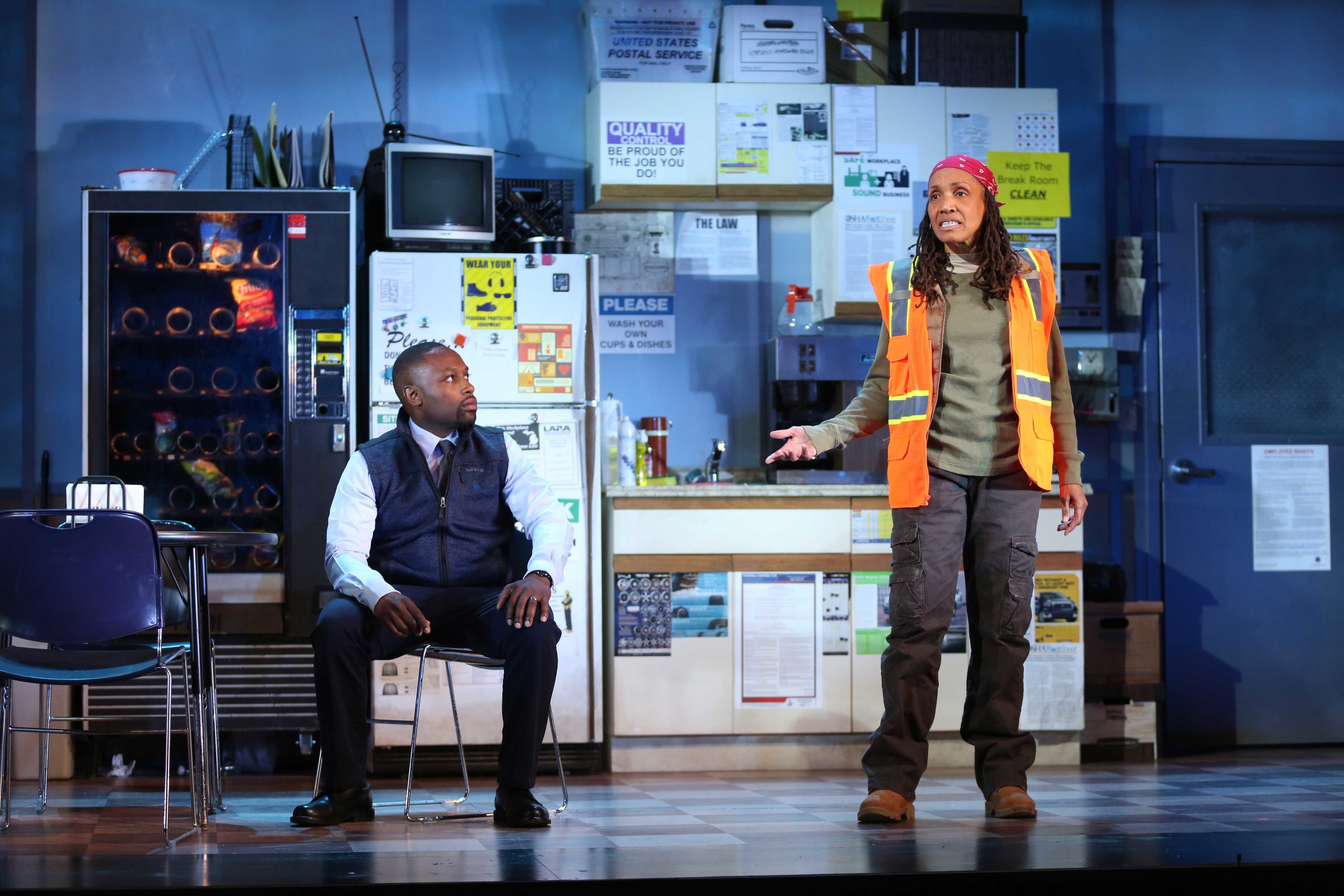

Finally, there’s Reggie, the middle-management guy in a tie who has to figure out how to remain loyal to his workers without ruffling his bosses. Faye is a friend of his late mother’s who got him a job at the plant in the first place and she’s also the shop’s union representative. The tensions that come with being friends—almost family—and co-workers at different paygrades play out as the play goes on. Sean Nelson’s performance is pitch perfect, particularly when he must confess to Faye an angry misstep that may have dire consequences. Nelson lets us see the fire that Reggie represses to walk the line he does.

Reggie (Sean Nelson), Faye (Perri Gaffney) (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Skeleton Crew isn’t a gimmicky play; there are a few key props that add extra drama, but the story is conveyed entirely by the interactions of these four vivid characters. In LA Williams’ tight direction, the pacing and transitions are deliberately naturalistic—most scenes open with the workers arriving for their shift, though a few scenes also take place at the end of breaks or, in one key instance, after working hours. Particular problems may differentiate these characters, but we’re always aware that they’re experiencing—to alter the old adage—“same shit, different person.” Each has their individual griefs, but the threat of a shutdown impacts them all.

The crap that’s coming down on this particular outmoded form of capitalist excess is apt to bury them, but Morisseau has the instincts of a popular writer and that keeps the mood from becoming too grim. There are moments of real human caring and sharing and that’s what keeps the drama buoyant. As a slice-of-life play, Skeleton Crew might feel as outdated as the way of life that Motor City once sustained. And that’s part of the play’s charm, letting us settle in to an American story of work that will be familiar to many, and then unsettling us with the fears besetting those with no safety nets as the public good becomes a casualty of private interests.

Reggie (Sean Nelson), Faye (Perri Gaffney), Shanita (Toni Martin), Dez (Leland Fowler) (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Unlike the other two entries in Morisseau’s trilogy, Skeleton Crew doesn’t need to work through historical references to expand the story’s dimensions. The reality of big business in flight from the U.S. has been with us since the 1970s and, though specific here to Detroit, is common enough throughout the northeast where this play should resonate with audiences who’d like to meet everyday heroes.

Skeleton Crew

By Dominique Morisseau

Directed by LA Williams

Scenic Design: Caite Hevner; Costume Design: Asa Benally; Lighting Design: Xavier Pierce; Sound Design: Chris Lane; Dramaturg: Sandra Daley; Props Supervisor: Samantha Shoffner; Dialect Coach: Ron Carlos; Production Stage Manager: Bryan Bauer; Original Music by James Keys

Cast: Leland Fowler, Perri Gaffney, Toni Martin, Sean Nelson

Westport Country Playhouse

June 4-22, 2019