Review of Kennedy: Bobby’s Last Crusade, Playhouse on Park

This election season, fraught as it is with peril—in the form of a pandemic the U.S. has handled badly—chaos—in the form of showdowns between heavily armed squads and protesters enraged by unconscionable and racialized acts of police violence—and a do-or-die aura for our beleaguered electoral system, why not return to a period just as anxious and portentous? Well, except there was no internet then.

In 1968, the Democratic party had a sitting president, Lyndon Johnson, who was becoming increasingly unpopular with many of his constituents, particularly those who wanted the undeclared war in Vietnam to end. That led to divisions within the party that, to a certain extent, never got completely healed. Senator Eugene McCarthy was running against the president on a ticket mainly aimed at young voters who had the most to lose by the war dragging on and who were becoming increasingly vocal. 1968 was the year student unrest closed many campuses during spring session, and May ’68 is well known as the fulcrum moment when protests by French students and workers shut down Paris. It was also the year of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China.

Goaded into running by a sense that history was passing him by, Robert Francis Kennedy, brother of assassinated and much mourned president John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and former attorney general in his brother’s administration, entered the race for the Democratic nomination in March. In June, two months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Kennedy was assassinated, having just won the California primary.

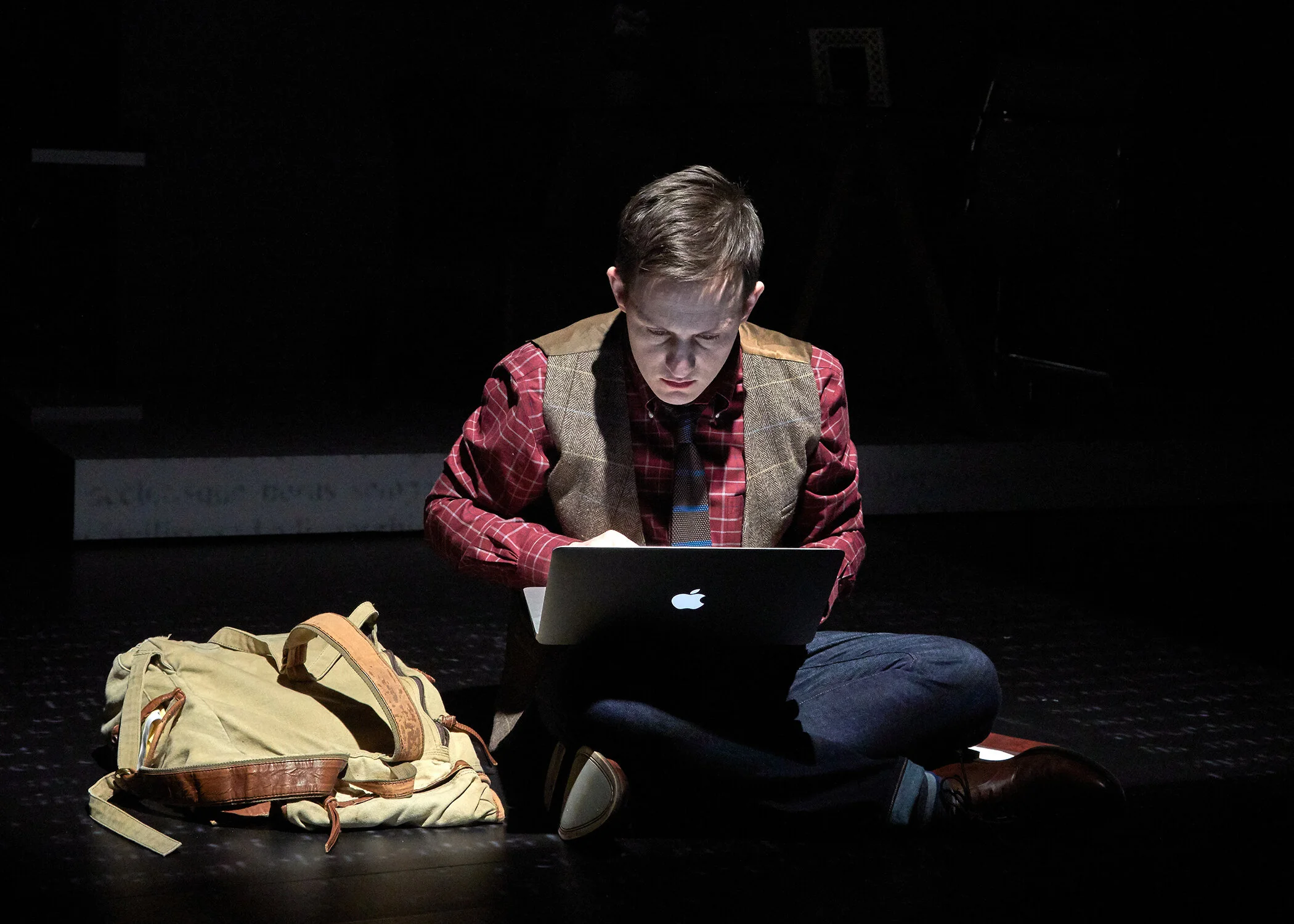

David Arrow (Bobby Kennedy) in KENNEDY: BOBBY‘S LAST CRUSADE, filmed for Playhouse on Park. Photos by Russ Rowland

Kennedy: Bobby’s Last Crusade by David Arrow, who plays Kennedy, directed by Eric Nightengale, tours the series of stump speeches Kennedy made in those heady times. Much of the power of the play comes from hearing literate, compassionate speeches that don’t sound like mere rhetoric or designed merely to score points off opponents. We see Kennedy is fond of quoting “his favorite poet” Aeschylus (well, a Kennedy probably should have a tragic view of life), and that he has taken up the war on poverty that was one of the better aspects of the Johnson administration. We hear some of his candid asides on his own performance, see his personable sense of his developing public persona, and live through some touching and, now and then, light-hearted moments. The play documents how in the course of those three months Kennedy, an inheritor of incredible privilege thanks to his father’s wealth and power, transformed himself into a man of the people. It wasn’t an act, and that, if nothing else, is why people still get misty when they talk about “Bobby.”

And that’s mostly the tone of the play, a kind of tempered hagiography, with each successive speech, most in the Midwest, a stop on a kind of Via Crucis. Whatever you may think about the Kennedys, the fact of their brutal and untimely deaths—for political reasons, no matter which account of guilt you believe—makes them at once more sinned-against than sinning. We don’t hear much about what made Kennedy a man with so many enemies, nor do we get much of a sense of Kennedy as the tough and shrewd politician he was. By which I mean to say that he was under no illusions about how nasty it all could get, yet the feeling of the man the play gives us is a bit of a naïf. I don’t doubt he was overwhelmed by the Sinatra-like (or Beatles-like) hysteria he was often greeted with—remarking on how often someone in the crowd stole his shoe—but any chance he had for election meant stirring and feeding and riding just such a reaction. The five years of shock, mourning and disquiet since the death of his brother made the mere presence of a Kennedy an oracular and revelatory moment to his followers. The Kennedy phenomenon was in full swing.

David Arrow (Bobby Kennedy) in KENNEDY: BOBBY‘S LAST CRUSADE, filmed for Playhouse on Park. Photos by Russ Rowland

The two immediate targets of the excerpts we hear from Kennedy’s speeches—McCarthy and Johnson—are men Kennedy respects, though, having been in the JFK administration with Johnson, he has no illusions about the kind of hardball political animal he’s dealing with. Then, in a speech on the eve of April Fool’s Day, just days before King’s assassination, Johnson announced he would not seek or accept his party’s nomination. The ostensible reason (no, not to spend more time with his family) was to put all his efforts into ending the war. Thereby quenching, potentially, the fire of much of the McCarthy and now Kennedy campaigns. If you believed him. Eventually Vice President Hubert Humphrey would take up the mantel of running as the preferred DNC front-runner. And what we witness in the play, as history shows, is that Kennedy, in just three months, was mounting a formidable challenge. Thus engendering one of the great “what-ifs” of party politics for that generation.

And that’s the main effect of the play: inspiring—besides admiration for the articulate, thoughtful, driven Kennedy, who never loses his sense of humor—thoughts of “what if.” And maybe, “what now?” Or “why not?,” recalling the famous tagline, stolen from George Bernard Shaw, with which Kennedy ended many of his speeches during the campaign: “Some men see things as they are and ask why? I dream things that never were and ask why not?”

As Kennedy, David Arrow does a remarkable job. He has the Kennedy quaver at times, and he can drawl out certain Boston inflections well enough to bring back those familiar voices. More keenly, his Kennedy takes us into his confidence, giving a chummy backstage access to the events as he lives them. There’s an immediacy that no documentary portrayal could achieve and that makes the play riveting—which is amazing, considering that most of the time we’re listening to campaign speeches (generally one of the lowest forms of theater). There are videos to show us newspaper headlines, views of crowds, and some of the faces of key figures of the time. The set has the look of the shambles of campaign headquarters after a grueling night.

For those who remember RFK (I was eight when he died, and can still recall getting up for school on June fifth, my brother’s second birthday, with the television proclaiming the news from California of the shooting; Kennedy died in the morning of the sixth), the play helps jog the memory—like the very real unease with the length of Kennedy’s hair in those days when such things were emblems of embracing the dangerous youth culture. For those who didn’t live through those times, the play is bound to feel a bit remote—Kennedy was dead before current presidential candidate Joe Biden was elected to his first term as senator—but it may be just the thing to stir youthful belief in the power of change.

The play is apropos in the way that some of Kennedy’s characterizations of current events describe our own times, but more importantly it reminds us that political leaders can sometimes galvanize the best and brightest hopes. As Kennedy said in his early campaign speech at the University of Kansas: “…hundreds of communities and millions of citizens are looking for their answers, to force and repression and private gun stocks - so that we confront our fellow citizen across impossible barriers of hostility and mistrust and again, I don't believe that we have to accept that. I don't believe that it's necessary in the United States of America. I think that we can work together - I don't think that we have to shoot at each other, to beat each other, to curse each other and criticize each other, I think that we can do better in this country. And that is why I run for President of the United States.”

David Arrow (Bobby Kennedy) in KENNEDY: BOBBY‘S LAST CRUSADE, filmed for Playhouse on Park. Photos by Russ Rowland

The heartbreak of the story—which wouldn’t surprise Aeschylus—is that the gods are cruel.

Notes from Playhouse on Park:

This is a film of the play. This play was originally scheduled to be produced by Playhouse Theatre Group, Inc. live at Playhouse on Park. As a result of guidelines put forth by both Governor Ned Lamont and Actors Equity Association, the play could not be produced in front of a live audience, nor could it be filmed in CT. The play was filmed for Playhouse on Park audiences at the Theatre of St. Clements in NYC. This is the same place it had its world premiere in 2018. The film is available to stream at home between September 16 - October 4 for $20; NOW EXTENDED TO OCTOBER 11.

On Saturday, October 10, Playhouse on Park is bringing the filmed play KENNEDY: BOBBY’S LAST CRUSADE to Edmond Town Hall for The Ingersoll Auto Pop-Up Drive-In. The film will start at 7:30pm (gates open at 7pm). $20 per car. Playwright/Actor David Arrow and Director Eric Nightengale will be in attendance. We are working on a creative way to conduct a Question and Answer Session! Please plan on joining us. For tickets: here

Kennedy: Bobby’s Last Crusade

By David Arrow

Directed by Eric Nightengale

Starring David Arrow as Bobby Kennedy

Filmed for Playhouse on Park

Available for streaming: September 16-October 11, 202