Review of Pride and Prejudice, Hartford Stage

The 60th anniversary season of Hartford Stage is off to a crowd-pleasing start. Playwright and actress Kate Hamill specializes in lively, contemporary adaptations of classic novels. Her bright and fun take on Jane Austen’s beloved Pride and Prejudice is given a fully frenetic realization by director Tatyana-Marie Carlo. The cast is having so much fun it all feels quite infectious.

Lydia (Zoë Kim), Mary (Madeleine Barker, back), Mrs. Bennet (Lana Young), Lizzy (Renata Eastlick) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The plot, as you may already know, is about those Bennet sisters (here four instead of Austen’s five) residing in Regency era England. Not badly off, the young ladies are doomed to penury whenever their aloof, paper-reading pater (Anne Scurria) kicks off. A cousin—the daffy curate Mr. Collins (Sergio Mauritz Ang)—will inherit. And so Mrs. Bennet, played to the hilt and then some by Lana Young, urges upon her daughters any suitor likely to remain smitten long enough to reach the altar. Besides Collins, there’s also the very well-to-do Bingley (also Ang), and the perhaps not all he should be Wickham (also Ang), a mere lieutenant with whom Mr. Darcy (Carman Lacivita) has had disagreeable dealings. Darcy himself, the only potential suitor not played by the versatile and quite comic Ang, is given all the priggish airs you might expect in Lacivita’s icy performance. Watching him thaw despite himself is much of the fun.

Lizzy (Renata Eastlick), Jane (María Gabriela González) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

As the sisters, María Gabriela González is a lovely Jane, the one deemed a catch due to her looks, and she’s also able to twerk on beat; as Lizzy, the main heroine, Renata Eastlick is sensible and likeable, her intelligence and ease of manner making her the best Lizzy I’ve seen (this is the third version of Hamill’s play I’ve reviewed); as Lydia, the youngest, Zoë Kim somehow manages to be a credible fourteen year old, crazily spirited with a feisty naivete that Lydia would like to think precocious; then there’s Mary, whom Madeleine Barker plays as a cross between the Addams family’s Morticia and that girl that crawls out of the TV set in The Ring—a kind of funny, frightening and striking character that has to be seen to be believed (and enjoyed).

Miss Bingley (Madeleine Barker), Mr. Darcy (Carman Lacivita) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Other characters played by this energetic cast include: Madeleine Barker’s supercilious turn as turbaned Miss Bingley, sister of Bingley—who tends to approach romance as would an affectionate pet; Anne Scurria scurrying between wearing Mr. Bennet’s pants and neighboring would-be bride Charlotte Lucas’s skirts; Zoë Kim, moving effortlessly between Lydia pouting and preening to the imperious mien of Lady Catherine de Bourgh (deep fanfare!); and last but not least, María Gabriela González’s hilariously unearthly sounds as Miss de Bourgh, a neurasthenic shambles swaddled like a mummy and, in Lady Catherine’s view, the perfect match for perfectly detached and unattached Mr. Darcy.

Miss de Bourgh (María Gabriela González, back), Lady Catherine de Bourgh (Zoë Kim) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The show opens with one of those mannered dances dear to the period, a signal that Carlo’s take is not going to foreground the gamesmanship that Hamill herself underscores via Lizzy’s comments on marriage as a contest with winners and losers; rather, the Hartford Stage production seems rather to concern itself with ritual and theatrics, seeing in the mating game the setting for so much of our ideas of how to act, look, dress, speak, move and so forth. Watching the varied displays of this busy staging is to glimpse what it’s like to live in a culture where someone is always watching, where public events—like balls (and how Mrs. Bennet loves balls!)—are occasions as deliberate as putting on a play. It’s all show-biz? Yes, and then some.

Lizzy (Renata Eastlick) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Lizzy, famously, is having none of it, until . . . As her doting dad says on two occasions, “ask not for whom the bell tolls.” When Lizzy has to confront her own feelings she has to do so without the kinds of pretense that serve so well the game or ritual or manner of this comedy of manners. Did anyone ever get so great a reaction from setting a sheet of paper in front of a sodden suitor?

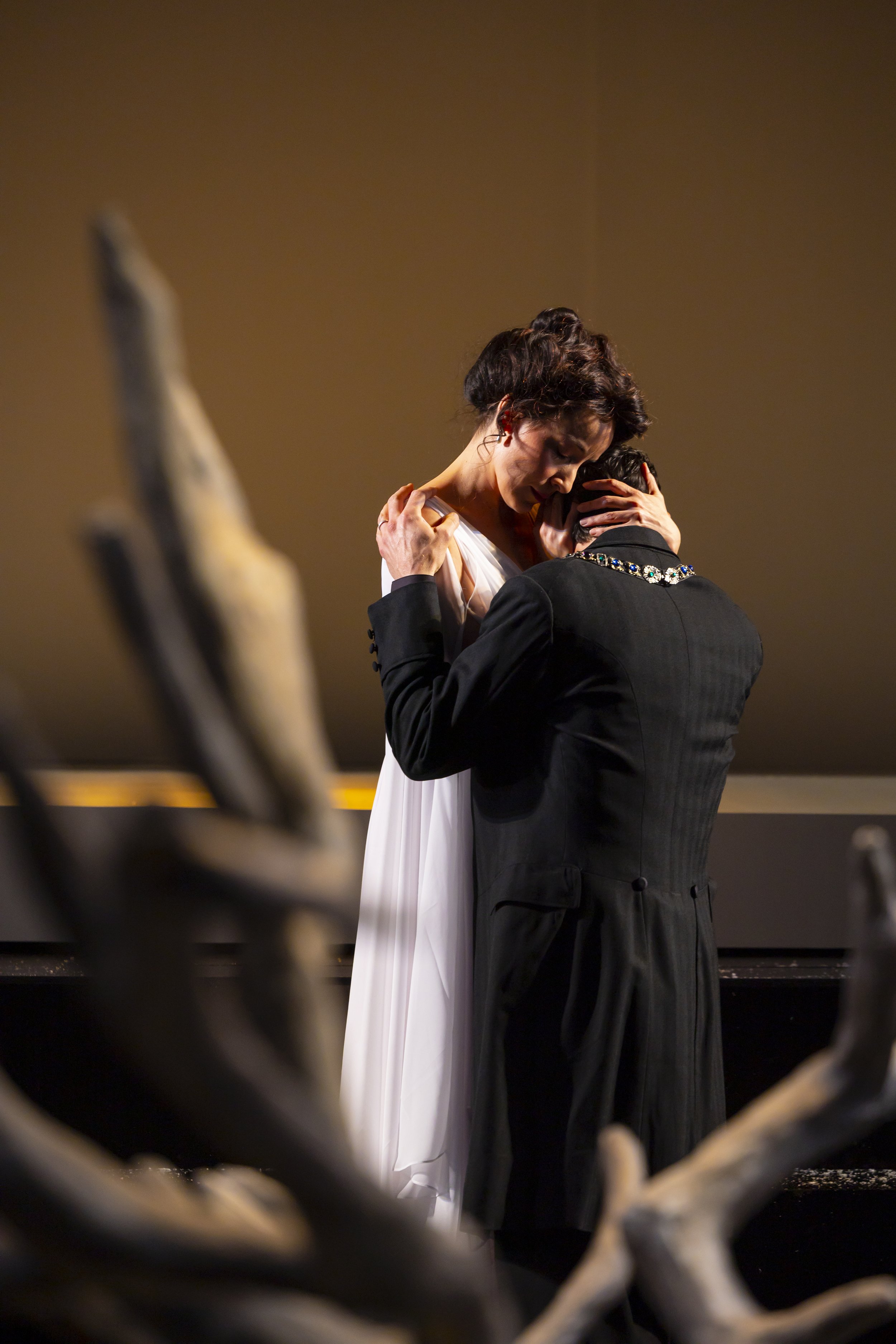

Mr. Darcy ( Carman Lacivita), Lizzy (Renata Eastlick) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Such are some of the many delights enacted here. Prepared to be tickled by things like Mr. Bennet brandishing a wig atop a stick draped with tatters of fabric to stand in for Mary (Barker then onstage as Miss Bingley), or the many times a little bell is rung to precede a visitor/suitor or other perhaps game-changing announcement, or the many times a cast member must react with surprise, shock or horror at the sudden appearance of Mary—as well as matters a bit more subtle, such as the way Lydia precipitates herself into wedlock not thinking that in “winning” (by being the first daughter married) she has lost something she might only begin to understand now; or the way Charlotte finds a way to live with Mr. Collins, as he crows offstage about his garden growths; or the way Mr. Bennet imagines it is just possible he may outlive his dutiful wife, who is always so concerned with how the family will manage without him.

The cast of Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Such matters used to be called “the war between the sexes,” but Austen and Hamill know it’s not an outright war so much as an ongoing negotiation that both sides engage in for the thrill of it all. Otherwise, what is there to do? That question can’t honestly be asked in a culture where women cannot inherit and must marry so as to survive, where work, as such, is beneath everyone at this level of society, and so ladies must hitch their star to a man who has property or who is likely to rise socially. Sinecures are nice as well. While Austen’s novels tread this terrain with a knowing wink or grimace at all the subterfuges needed to achieve secure ends, Hamill can let it all hang out, placing the skirmish front and center with a kind of “on your mark, get set, go” urgency.

The cast of Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The matches made are the same but the spectacle they make is the fun. Ably supported by Hartford Stage’s large open playing space—making a drawing room or garden or ballroom very much a playground—decorated with Scenic Designer Sara Brown’s sense of how to create visual interest (early on, there aren’t enough chairs to go around so Lizzy must push a cushion to center stage), the show also benefits from Shura Baryshnikov’s varied Choreography, Aja M. Jackson’s subtle Lighting Design, original music and sound design by Daniel Baker & Co (there are also a few popular songs that anachronistically surface for comic effect), and, particularly, Haydee Zelideth’s fantasies of era Costumes, the colors tend to be rich—like Lizzy’s true blue Plain Jane gown—and patterns abundant, and where, as was true to the time, the flouncier your skirt the higher you stood in status so that Lady Catherine wears clothes that might well swallow a lesser being. Meanwhile, Sergio Mauritz Ang gets to appear as curate, soldier, and affable love-smitten coxcomb by turns, switching costumes and mannerisms as needed. It’s dizzying.

Mr. Bennet (Anne Scurria, back), Mary Bennet (Madeleine Barker) in Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice at Hartford Stage (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Mary—ever ready to announce an apothegm scored from the manners on display around her—at one point points out the difference between pride and vanity. No one listens, but we hear her, and her comment serves well the entire production. To be vain is to be concerned with what others think of you; to be proud is to esteem yourself for your own virtues. Tatyana-Marie Carlo’s version of Kate Hamill’s Pride and Prejudice, from Jane Austen’s novel, at Hartford Stage through November 5, has much to be proud of.

Pride and Prejudice

By Kate Hamill

Adapted from the novel by Jane Austen

Directed by Tatyana-Marie Carlo

Choreographer: Shura Baryshnikov; Scenic Design: Sara Brown; Costume Design: Haydee Zelideth; Lighting Design: Aja M. Jackson; Original Music & Sound Design: Daniel Baker & Co.; Wig Design: Earon Nealey; Vocal & Dialect Coach: Jennifer Scapetis-Tycer; Fight Director: Teniece Divya Johnson; Casting: Alaine Alldaffer; Production Stage Manager: Anaïs Bustos; Assistant Stage Manager: Theresa Stark; Associate Artistic Director: Zoë Golub-Sass; Director of Production: Bryan T. Holcombe; General Manager: Emily Van Scoy

Cast: Sergio Mauritz Ang, Madeline Barker, Renata Eastlick, Maria Gabriela González, Zoë Kim, Carman Lacivita, Anne Scurria, Lana Young

Hartford Stage

October 12-November 5, 2023