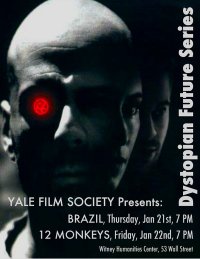

Terry Gilliam’s latest film, The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus, is currently playing at the Criterion Cinema in New Haven, but I haven’t seen it yet. However, two unique films directed by Gilliam (which I consider his best, or are at least the ones I remember best), Brazil (1985) and 12 Monkeys (1995), are showing tonight and tomorrow night, respectively, at the Whitney Humanities Center on Wall Street, at 7 p.m., courtesy of The Yale Film Society and Films at the Whitney. Not wanting to give anything away, if you haven’t seen these films, I’d say they’re well worth your attention if you like fables of the future with a quirky relation to the present. Do I mean the present when the films appeared or the current present? Both, I think.

Brazil is set in a kind of Orwellian future that knows itself to be Orwellian -- the way that Orwell’s 1984, ostensibly set in 1984 but written in 1948, has a relentless feel of the immediate post-WWII world. Brazil is like that too: it looks like a future that dates back to Orwell’s 1984 as homage (the film appeared in 1985, note) and as comment on the datedness of the kind of dystopia it re-imagines for us. A Ministry of Information “sometime in the 21st century” that uses pneumatic tubes for interoffice communication? Computer consoles that look like ham-radios with screens? Warrens of nameless workers who are only male and wearing suits that look like the ‘40s?

But there are elements that make it feel ‘80ish too: fashion statements such as a stunning hat that actually appears to be a ladies’ leopard-print high heel inverted on the wearer’s head; increasingly disastrous cosmetic surgery interventions; a female heroine with short spiky hair who is more butch than the willowy male hero (a twitchy, sadsack Jonathan Pryce); add to this the vast sets that recall, deliberately, Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and you have something like a retro-chic version of how the police state might morph before the millenium.

There’s plenty of Gilliam’s characteristic wide-angle and fish-eye camera work, lots of visual distortion, evocative uses of lighting and scale and, as usual with the former Monty Python animator, endless visual fun, including a Battleship Potemkin reference (in “the director’s cut,” at least) to give filmbuffs a laugh. And the story -- with threats of sabotage and terrorism against the state fleetingly evoked, and the Orwellian catchphrases posted in the background: “Truth is Information”; “Trust in Security” -- stills holds up and maybe resonates as much now, post-W., as it did shortly after Reagan’s re-election.

12 Monkeys is set in the future, but not so distantly. James Cole (Bruce Willis) was about 8 in 1997, the year when a viral plague wiped out most of the human race. Now he’s about 40, sent back to 1996 to try to gather information that will help scientists in the present day (when everyone is living underground) find an antidote to the plague. The basic situation of the film – time travel to the past to counteract the post-apocalyptic present, and the dramatic detail of the killing in the airport -- derives from Chris Marker’s film La Jetée (1962). But Gilliam brings to the material lots of fun, whacked-out stuff.

And keeps it interesting and mysterious. A first viewing really plays with your head, much as the various “endings” of Brazil do. And the visual palette is ramped up with chatter and crosstalk from TV sets (broadcasting the Marx Bros.’ Monkey Business, for instance), films (hiding out in a cinema while Vertigo is onscreen), music (one of my favorite moments is the look on Willis’ face when he hears, on his first trip back to‘96, Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” on the radio), and the kind of beat futurisitic clutter held over from Brazil.

Other pleasures include a desolate, post-apocalyptic Philadelphia (and a not-so pleasurable version of that city, c. mid ‘90s, that looks truly distressed); also, Brad Pitt, as a psychotic scion of a rich magnate of biochemical products, is all quirks, trippy chuckles and frenetic hand gestures and mismatched eyes, heading the political group 12 Monkeys, dedicated to animal and environmental rights, but which might be moving toward terrorist or guerilla acts -- again, a timeliness all-too-apparent for today’s viewers.

The apocalypse in Marker’s film was nuclear-based; in Gilliam’s it’s viral, but there’s enough environmental sentiment present, together with dismay at the human race -- and stunning shots of an array of African animals loose in the streets of Center City -- to fuel whatever global-warming apocalypse scenarios might be circulating in the brain of the 21st-century viewer.