Review of Re:Union, Yale Cabaret

The fraught sacrifice required by war is given an unusual spin in Sean Devine’s Re:Union. The war dead are in most cases those who fought and died, on either side. In the case of the story of Norman Morrison, the part of civilian casualty of war takes on a different dimension—not only of a personal sacrifice but also of public protest.

In 1965, as the war in Vietnam escalated, Morrison, a married Quaker teacher and father of three, staged a self-immolation outside the Pentagon window of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. The event was one of a few such protests on U.S. soil, perhaps spurred by the famous coverage from 1963—including photos and film footage—of a Vietnamese monk lighting himself on fire in Saigon in a call for religious equality after Buddhist monks were killed by government forces in South Vietnam. In the case of Morrison, the choice of location and the fact that his three-year-old daughter, Emily, was in his arms at least until he doused himself in kerosene, added not only more potential symbolism to his act but also more mystery and drama.

Emily Morrison (Louisa Jacobson), Robert McNamara (Charles O'Malley) (Photographs by Johnny Moreno)

Re:Union capitalizes on the degree to which Morrison’s act was likely meant as, and was certainly viewed as, an indictment of McNamara specifically, as the man who, at that time, argued most pervasively that the war could be won. The play’s main action takes place in 2001 when Emily (Louisa Jacobson), now in her thirties, confronts McNamara (Charles O’Malley) about the escalating war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. She’s seeking a means to protest the Patriot Act as sanctioning tyranny, but is also, as becomes clear, looking for a way to come to terms with the past.

The play, which has been shortened for the Yale Cabaret’s running time with the permission of the author, triangulates the action by showing us, 1) Norman teaching a lesson on Kierkegaard’s reading of the story of Abraham and Isaac, in 1965; 2) Emily, in 2001, addressing both McNamara and her father on video, as well as, eventually, McNamara in person, and 3) staged “clips” of McNamara, during his time in the Pentagon, addressing the press or TV in various contexts, and, eventually speaking with Emily.

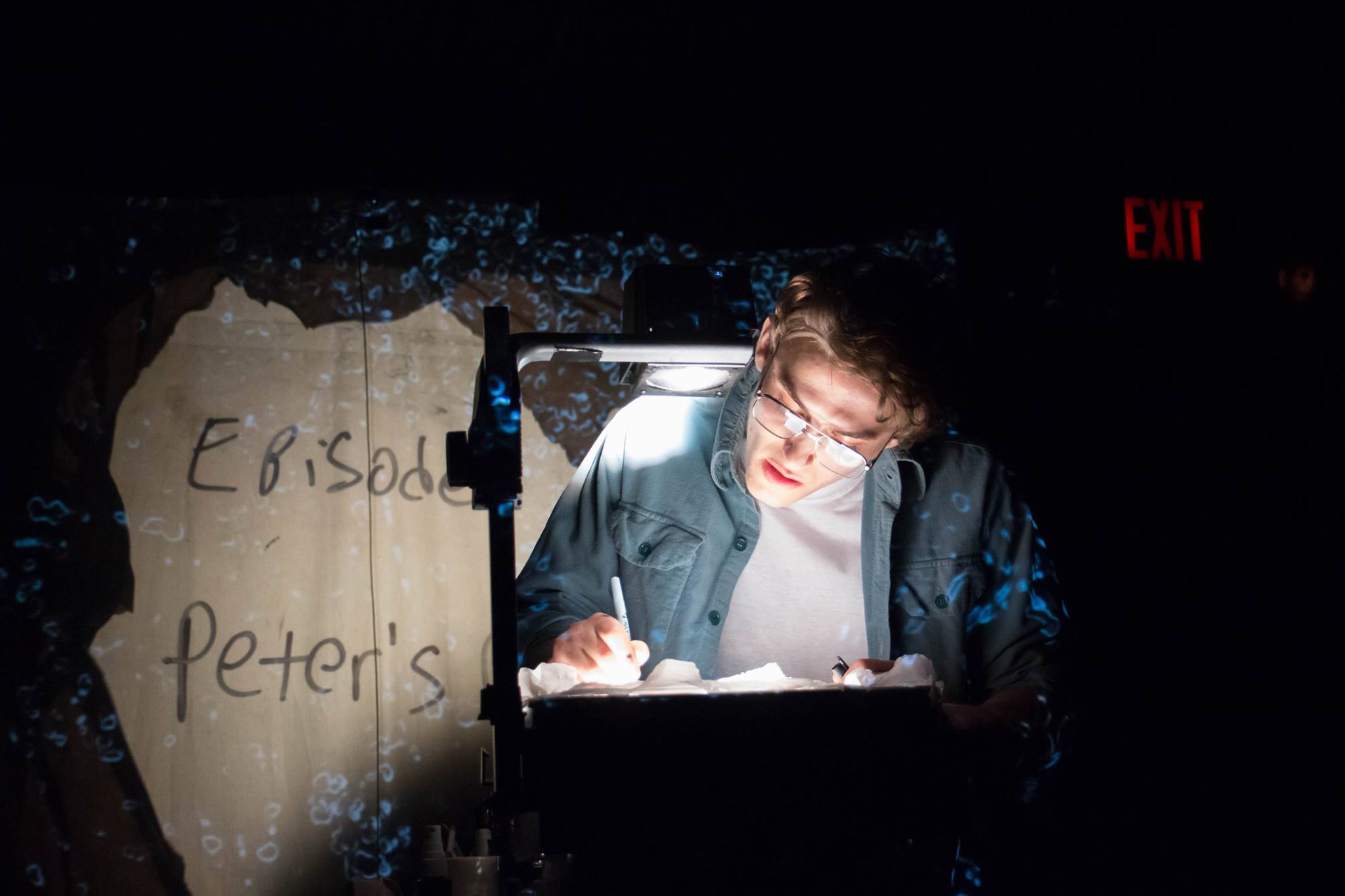

Director Jecamiah Ybañez and the production's proposer and projection designer Wladimiro A. Woyno R. evoke the varying levels of conscience through trenchant overlaps, so that the story and its ramifications seem to occupy a claustrophobic, obsessional mental space. Emily speaks into a camera which projects her image on screen, as she tries to find the words that would elicit a sense of complicity from McNamara; McNamara, always very poised and relentlessly dry, expounds his war strategy to unseen listeners or deflects criticisms with a lofty tone; Norman, with cute overhead projections, expounds on Abraham’s pact with God, then announces that God has shown him his purpose. As Norman, Jared Andrew Michaud, in a Cab debut, moves from a driven teacher to an eerily detached zealot with only one purpose.

Norman Morrison (Jared Andrew Michaud)

Emily wants closure on the Vietnam War, as a misguided sacrifice of U.S. lives and the destruction of the land and peoples of the belligerent regions of Vietnam, even as the U.S. embarks vaingloriously, and some would say cynically, upon another costly military enterprise. While still personally troubled by her father’s act, Emily, played with an involving sense of conviction by Jacobson, ponders the effects of inaction. She’s not opening old wounds but rather showing that there has never been a return to health in the U.S.

But the play also reflects somewhat the change of heart toward the war that McNamara displayed in works such as the film The Fog of War (2003), and in his comments to Emily’s mother as recorded in the latter’s memoir. O’Malley plays McNamara as a bit of a Vulcan, all about rationality and the logic of his strategy. His main emotion is a certain vindictiveness toward Morrison for fouling the air so abysmally and causing him great personal distress. He seems at best petulant about the event, only gradually, and grudgingly, allowing that Morrison’s conviction caused him, at least to some degree, to question his own beliefs.

What comes out most forcefully in the Cabaret’s gripping and effective staging of the play is the extent to which McNamara demanded sacrifices of his country to an unconscionable degree or at least for a cause he found himself doubting. That demand is set against the faith of Morrison’s uncompromising act, which lets the cost of his loss fall upon his family. Both men, whether acting for the sake of God or for their country or for the dying Vietnamese, are willing to cause great suffering. Of the two, only McNamara had to live with that.

Emily Morrison (Louisa Jacobson)

Re:Union

By Sean Devine

Directed by Jecamiah Ybañez

Proposed by Wladimiro A. Woyno R.

Dramaturgs: Patrick Young & Alex Vermillion; Set Designer: Gerardo Diaz Sanchez; Costume Designer: Cole McCarty; Lighting Designer: Erin Earle Fleming; Projection Designer: Wladimiro A. Woyno R.; Sound Designer/Composer: Frederick Kennedy; Producers: Kathy Li & Laurie OM; Stage Managers: Cate Worthington & Madeline Charne; Technical Director: LT Gourzong; Associate Projection Designer: Brittany Bland

Cast: Louisa Jacobson, Jared Andrew Michaud, Charles O’Malley

Yale Cabaret

October 5-7, 2017