RFK, Music Theatre of Connecticut

It’s interesting that this election season has featured two very similar plays at area theaters. First, Playhouse on Park in West Hartford offered Bobby’s Last Crusade; now, Music Theatre of Connecticut is staging Jack Holmes’ RFK, directed by Kevin Connors. Both plays heroize and humanize the one-term New York senator, former U.S. attorney general, and assassinated Democratic presidential contestant Robert Francis Kennedy, the seventh of nine children and the third of four sons in the celebrated Kennedy clan. RFK was a charismatic, thoughtful and youthful politician—he died at age 42—who fathered eleven children, served in the administration of his elder brother President John Fitzgerald Kennedy where he took on organized crime, in the person of Jimmy Hoffa, and clashed with the F.B.I.’s domineering head, J. Edgar Hoover, and became, for a brief period in 1968, a figure for the hope for change in the Democratic Party which, at that point, had controlled the presidency for seven years and the U.S. Congress for thirteen and was embroiled in an undeclared war in Vietnam.

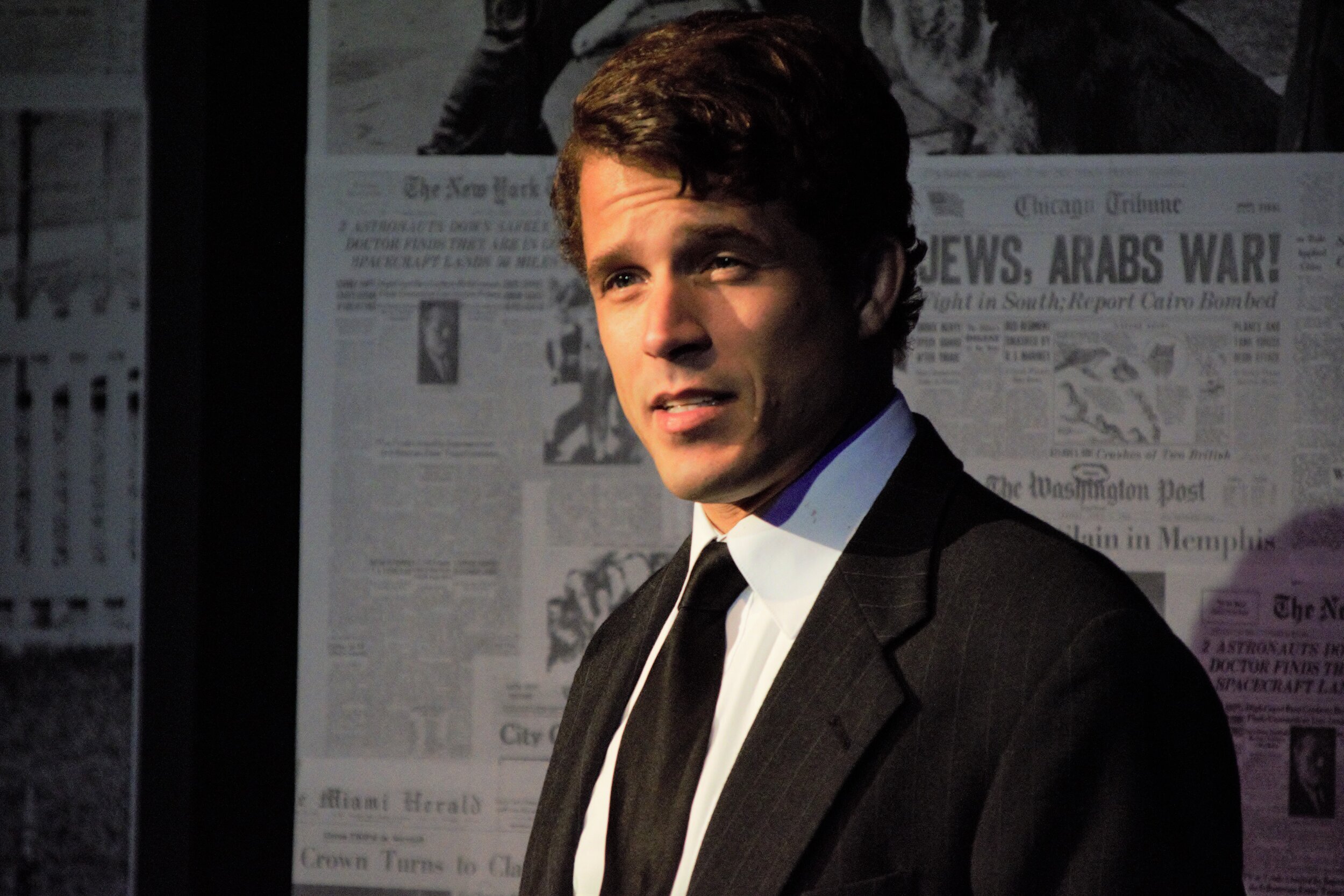

Chris Manuel as Robert Kennedy in RFK at Music Theatre of Connecticut, directed by Kevin Connors (photo by Alex Mongillo)

The dramatic core of RFK is only indirectly the legacy of Kennedy’s brother and former boss, President Kennedy. It’s a play about how Robert Kennedy found himself more and more convinced that he might be the man of the hour, and that the hour was getting late. His break with the policies of Lyndon Johnson, the sitting president and presumed candidate for reelection, was gradual and his decision to run against Johnson for the nomination came late in the election season. (One can’t help wondering if the return to 1968 in staging these two Kennedy plays is a way to remind us of how, once upon a time, members of the party in power took it upon themselves to run against sitting presidents when events warranted it.) At the end of March, Johnson announced his refusal to run for re-election and a surge of popularity for Kennedy indicated that perhaps a candidate other than one with “his pecker in [Johnson’s] pocket”—as the president put it—might carry the day. Then Kennedy was murdered early in June after winning the California primary.

As Kennedy, Chris Manuel—who has graced the stage in two previous excellent productions at MTC—is better at the more personable side of Kennedy, as when he talks about his reputation for making enemies as his brother’s campaign manager and then attorney general, or when he speaks of his relations with his family, including quips about “Teddy” (Senator Edward Kennedy who went on to serve over 45 years as a Massachusetts senator). The more rousing, public-speaking bits seemed to me lesser, but that may be only in comparison with the focus on the latter in Bobby’s Last Crusade and the way the candidate’s stump speeches were dramatized and contextualized in that play. At certain moments Manuel’s physical manner does recall the Kennedys—he most resembles RFK’s eldest son, Joseph, as a young man.

Chris Manuel as Robert Kennedy in RFK at Music Theatre of Connecticut, directed by Kevin Connors (photo by Alex Mongillo)

In any case, the strength of RFK is not the public Kennedy so much as the man behind the scenes. And here we get some well-chosen vignettes that go a long way to making us feel ourselves Kennedy’s confidantes. The play is staged on a nicely divided set by Jessie Lizotte: on the one side a desk, on the other a comfy chair. Holmes wants to register both the public and private man, but a scene of Kennedy in the armchair while being interviewed and interrupting himself to upbraid and beseech his obstreperous children makes the clash of the two sides more abrasive than amusing.

Most of the first part deals with Kennedy’s political career from 1964—when he found that Johnson would not offer him the VP spot in his bid for election as president—to 1966 and Kennedy’s inspired speech as a U.S. Senator visiting a South African university to give the Day of Affirmation Address. The speech, which closes Part 1, achieves the play’s rhetorical high-point, with its “ripples of hope” line, and with Kennedy saying:

“There is a Chinese curse which says, ‘May he live in interesting times.’ Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also the most creative of any time in the history of mankind. And everyone here will ultimately be judged—will ultimately judge himself—on the effort he has contributed to building a new world society and the extent to which his ideals and goals have shaped that effort.”

Challenging words to hear at this point in American political history, as they were then. And the second part of the play finds Kennedy trying to live up to the burden of that speech’s incentive.

Chris Manuel as Robert Kennedy in RFK at Music Theatre of Connecticut, directed by Kevin Connors (photo by Alex Mongillo)

In Part 2, Holmes chooses to juxtapose Kennedy’s imagined outbursts at “Johnny” (JFK) with Robert’s decision to run, making the announcement on the heels of a reflective recollection of his brother’s death and funeral. The words attributed to RFK have a groping quality, as if the situation—certainly unique to Kennedy—were being played simply for dramatic effect. The first half of the play, in its focus on Kennedy trying to decide what to do when no longer his brother’s attorney general, let us see Kennedy as a pragmatic political figure, and Bobby’s Last Crusade covers better the turn to becoming a presidential candidate. What RFK tries to give us, in Part Two, is the emotional underpinnings of that decision: we get a powerful story of Kennedy’s growing horror at the realities of poverty in the U.S. of the late 1960s, and stagey outbursts at JFK.

The details of Robert Kennedy’s death are narrated by Kennedy himself, though without directly addressing the fact of the assassination, much as he makes no comment about the cause of his brother’s death. In life, RFK spoke publicly about his belief in the findings of the Warren Commission’s report on the president’s assassination, but some who knew him denied that he accepted it or its methods. Holmes imagines RFK’s reaction to his brother’s death as a wail that it was he and not Jack who was the one “everyone hated.” Such comments, whatever their merit as off-the-cuff suggestions of character, downplay and undermine the drama of contested perspectives on the deaths of both men. There’s a huge area of uncertainty about those murders and it’s hard to say what the play RFK wants them to mean, offering us the drama of tragic loss rather than the drama that leads to tragic loss. The latter—as most great plays in the form show—is more telling.

Chris Manuel as Robert Kennedy in RFK at Music Theatre of Connecticut, directed by Kevin Connors (photo by Alex Mongillo)

What we have instead of a play about the Kennedys that might put their lives and deaths into perspective is a play ostensibly from Robert Kennedy’s perspective that speaks with immediacy of his decisions, his reactions, his losses and victories, and ultimately shapes the major loss—his death—as ours.

RFK

By Jack Holmes

Directed by Kevin Connors

Scenic/Prop Design: Jessie Lizotte; Lighting Design: RJ Romeo; Costume Design: Diane Vanderkroef; Sound Design: Will Atkin; Production Assistant: Jack Parrotta; Stage Managing: Jim Schilling

Cast: Chris Manuel

Music Theatre of Connecticut

October 23-November 8, 2020

Fridays at 8pm, Saturdays at 2pm & 8pm, Sundays at 2pm.

In person performances at MUSIC THEATRE OF CONNECTICUT

Live streamed performances will be shown online through a link provided to ticket holders an hour before their show time