Review of Native Son, Yale Repertory Theatre

If he were white, Bigger Thomas, the main character in Richard Wright’s Native Son, would be called a classic anti-hero. He makes bad decisions, and he kills women, both accidentally and deliberately. In the hard scrabble streets of 1930s Chicago, Bigger schemes a heist he’s unable to pull off and, for much of the novel, runs from the law and then, arrested, finds a defender. But in making this character an African-American struggling with the harsh conditions furnished by endemic racism and the perpetuation of a hapless underclass, Wright’s great contribution to American literature was finding a way to make such a person become a figure for cathartic portrayal. Bigger’s struggle, while still making us uneasy as anti-heroes do, is a heroic confrontation with a criminal status quo.

Adapted for the stage by Nambi E. Kelley, first at Chicago’s Court Theatre and now playing at the Yale Repertory Theatre, Native Son presents Bigger Thomas (Jerod Haynes, reprising the role he has played in two previous productions) as a man rather passively accosted by harsh fate. Things start badly—we see him unwittingly kill his employer’s daughter out of fear of discovery before we even grasp the situation—and then get worse in a wrenching downward spiral that Kelley and director Seret Scott, who has helmed all three productions, make us ride with Bigger in a swift 90 minutes to an inevitable end.

The play’s most marked feature is its compression. The action on stage recreates the non-linearity of Bigger’s recollections and fantasies interleaved with the inexorable events that overtake him. Kelley’s text depends on lightning-fast changes, where a phrase ending one scene might be the start of the next, and where action overlaps and reactions can stretch between scenes. It’s incredibly compelling and mostly flawless in its execution by a cast that works hard to keep the different trains running.

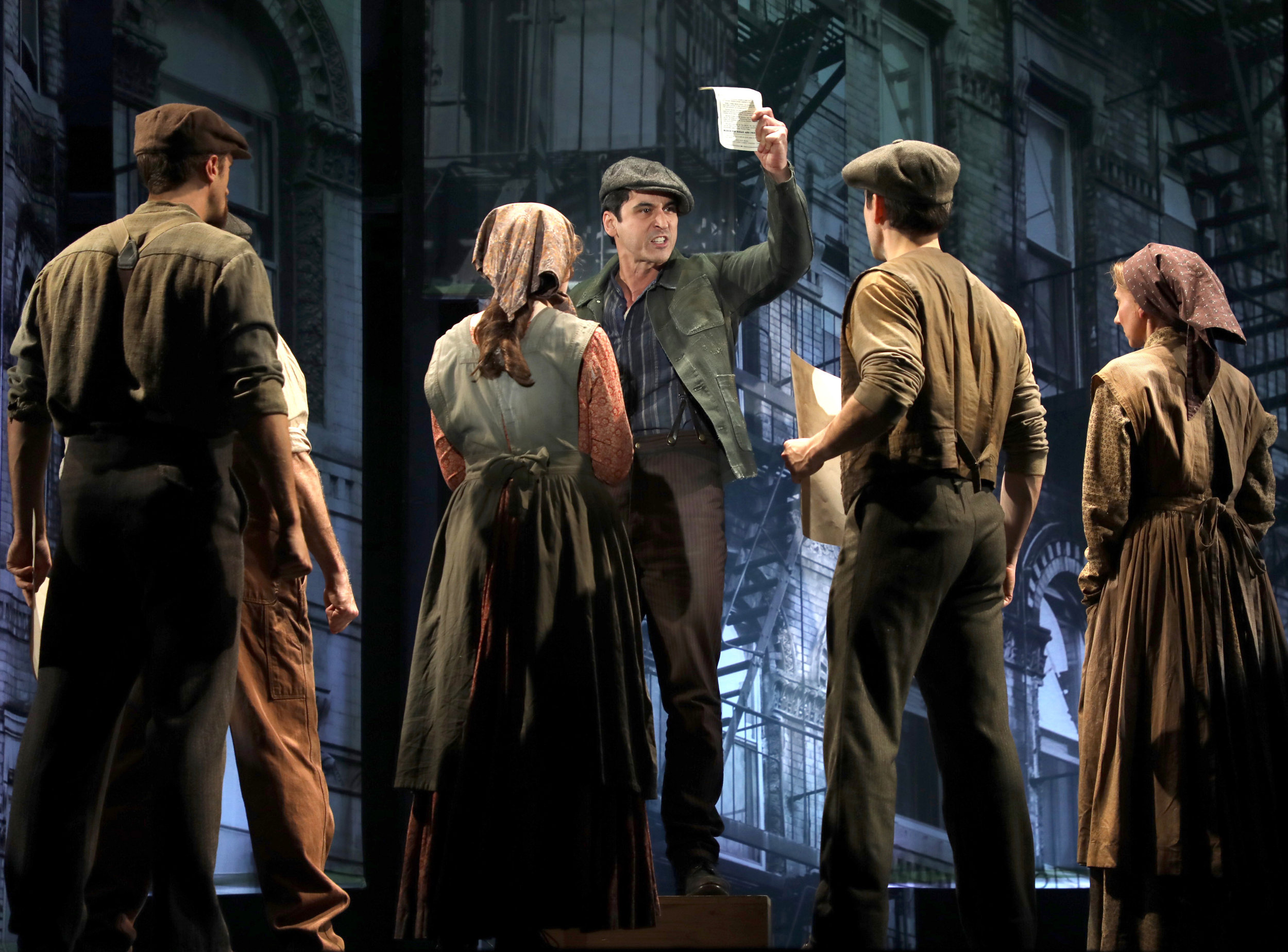

The cast of Native Son at Yale Repertory Theatre (photos: Joan Marcus)

Striking features of the show include Ryan Emen’s set, comprised of towering tenement buildings with fire escapes; Stephen Strawbridge’s lighting, a carefully calibrated mix of film noir, naturalism, and expressionism; and sound designer/composer Frederick Kennedy’s moody use of jazz music together with crucial sound effects—pool balls, car doors, a crunching skull. It’s a dark play and the Yale Rep production skillfully renders this particular hell.

The visual and aural features are key as the play’s action seems to inhabit a kind of internal theatrical space in Bigger’s mind. Bigger’s actions and memories are commented on by a double/foil called The Black Rat (Jason Bowen). The character takes his name from the scene of “how Bigger was born”: still a teen, Bigger has to kill a large black rat in the family’s substandard dwelling. The event, we might say, impresses on Bigger his abject conditions and a strong survivalist core, an “it’s them or me” outlook that returns, most drastically, when he faces a decision about his sometime lover Bessie (Jessica Frances Dukes, the play’s most sympathetic character)—“Can’t leave her, can’t take her with.”

The Black Rat (Jason Bowen), Bigger (Jerod Haynes)

The interplay of Bigger, who Haynes plays as a strong, brooding type, with The Black Rat, a cynical pragmatist, sustains the play’s development, as most of the other interactions are more emblematic than deliberated. For instance, Mrs. Dalton (Carmen Roman, another veteran of the play), is a blind rich lady who employs Bigger as a chauffeur. She tries to appear sympathetic to Bigger despite the fact that she’s complicit, through real estate holdings, with the harsh conditions of the Thomas family and their neighbors. She’s blind both literally and figuratively.

Mary Dalton (Louisa Jacobson), Bigger (Jerod Haynes), Jan (Joby Earle), background: The Black Rat (Jason Bowen)

Scott and Kelley let characters be the types Bigger sees them as. An awkward flashback shows Bigger driving Mary (Louisa Jacobson), flapper-ish heiress of the Daltons, and her well-intentioned but condescending Communist beau Jan (Joby Earle, earnest). The couple’s effort to affect camaraderie with their servant makes Bigger uncomfortable and earns the Black Rat’s scorn. Other characters are mostly used for stock antagonisms: Michael Pemberton plays Britten, a detective whose casual racism makes him assume that Bigger, even if guilty, must have had a white accomplice for such a complex crime, and also a police officer who visits a more violent racism upon the Thomas family. The scene’s brutality is echoed in many of Bigger’s actions, such as bullying his brother Buddy (Jasai Chase-Owens), and in his treatment of hapless Bessie, a woman who sees through his lies at her own peril.

Bessie (Jessica Frances Dukes), Bigger (Jerod Haynes)

The fantasy scenes, which might give us access to the world Bigger either feels himself to be a part of or would like to be a part of, can be arrestingly odd. In one, Jan importunes Bigger, trying to understand his crime, and invites him for a beer; in another, Bigger’s mother, Hannah (Rosalyn Coleman), grovels at the feet of a steely Mrs. Dalton; and, in the most satiric, which almost suggests a different direction for the play, the white folks sing a vicious spiritual that urges Bigger “to surrender to white Jesus.”

Such scenes seem to function as asides; the main tensions of the play are contained in Bigger’s guilt and flight. The scene in which Bigger tries to rid himself of Mary’s body is harrowing in its stark necessity but also grimly comic. Haynes, who generally maintains a tone of barely mastered panic, tries to brazen it out and we find ourselves wishing that, just once, things would go his way and let Bigger outsmart someone.

As a “native son,” Bigger is born to a condition that deprives him of much in the way of interiority and aspiration, leaving him to depend on whatever street smarts he’s able to muster. The Black Rat is a figment of that way of life, telling Bigger at the outset: “How they see you take over on the inside. And when you look in the mirror – You only see what they tell you you is. A black rat sonofabitch.”

The cast of Native Son, left to right: Michael Pemberton, Rosalyn Coleman, Jessica Frances Dukes, Jerod Haynes, Carmen Roman, Louisa Jacobson, Joby Earle, Jason Bowen

Theatrically varied and energetic in its approach, Native Son demands and repays the attention of audiences serious about theater and the need to tell difficult stories.

Native Son

By Nambi E. Kelley

Adapted from the novel by Richard Wright

Directed by Seret Scott

Scenic Designer: Ryan Emens; Costume Designer: Katie Touart; Lighting Designer: Stephen Strawbridge; Sound Designer and Original Music: Frederick Kennedy; Production Dramaturg: Molly FitzMaurice; Technical Director: Jen Seleznow; Vocal Coach: Ron Carlos; Fight Director: Rick Sordelet; Casting Director: Tara Rubin Casting: Laura Schutzel, CSA; Stage Manager: Caitlin O’Rourke

Cast: Jason Bowen, Jasai Chase-Owens, Rosalyn Coleman, Jessica Frances Dukes, Joby Earle, Jerod Haynes, Louisa Jacobson, Michael Pemberton, Carmen Roman

Yale Repertory Theatre

November 24-December 16, 2017