Review of Tru, Music Theatre of Connecticut

In 1975, Truman Capote was a celebrity, someone—as he says in the play Tru now playing both live before audiences and on live streaming at Music Theatre of Connecticut in Norwalk, directed by Kevin Connors—“famous for being famous.” The basis for that fame began with Other Voices, Other Rooms in 1948, but really went mega with his groundbreaking study of a multiple homicide in 1959 Kansas in the best-selling “true crime novel” In Cold Blood (1966), subsequently made into a successful film. An earlier success was the novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958), made into a popular film by Blake Edwards.

His fame allowed Capote to maintain a jet-set lifestyle among the glitterati—aristocrats, celebrities, and the immensely rich. The immediate setting for Tru is Christmas of 1975, just after the publication in Esquire of excerpts from Answered Prayers, the unfinished manuscript intended to be his magnum opus. In the form now called autofiction, the stories were thinly veiled “fictional” and unflattering treatments of the high-rollers among whom Capote had been passing much of his time. The outrage was great, and Capote, as the play goes along, is still largely in denial of how bad the fallout will be.

All of which is just by way of background, as Capote, who died in 1984, is not quite the household name he used to be, back when his frequent appearance on talk shows, not least Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, kept him in the living rooms and bedrooms of America. The play, while it certainly goes over best for those with some prior awareness of Capote and some of the big names he drops, comes across regardless, due largely to Capote’s considerable charm and way with words (most of which are adapted from Capote’s interviews and writings). Actually, those with no previous opinion of Capote might find the play more entertaining than those for whom the sad fact of Capote’s deterioration as a writer and then as a social butterfly has more sting.

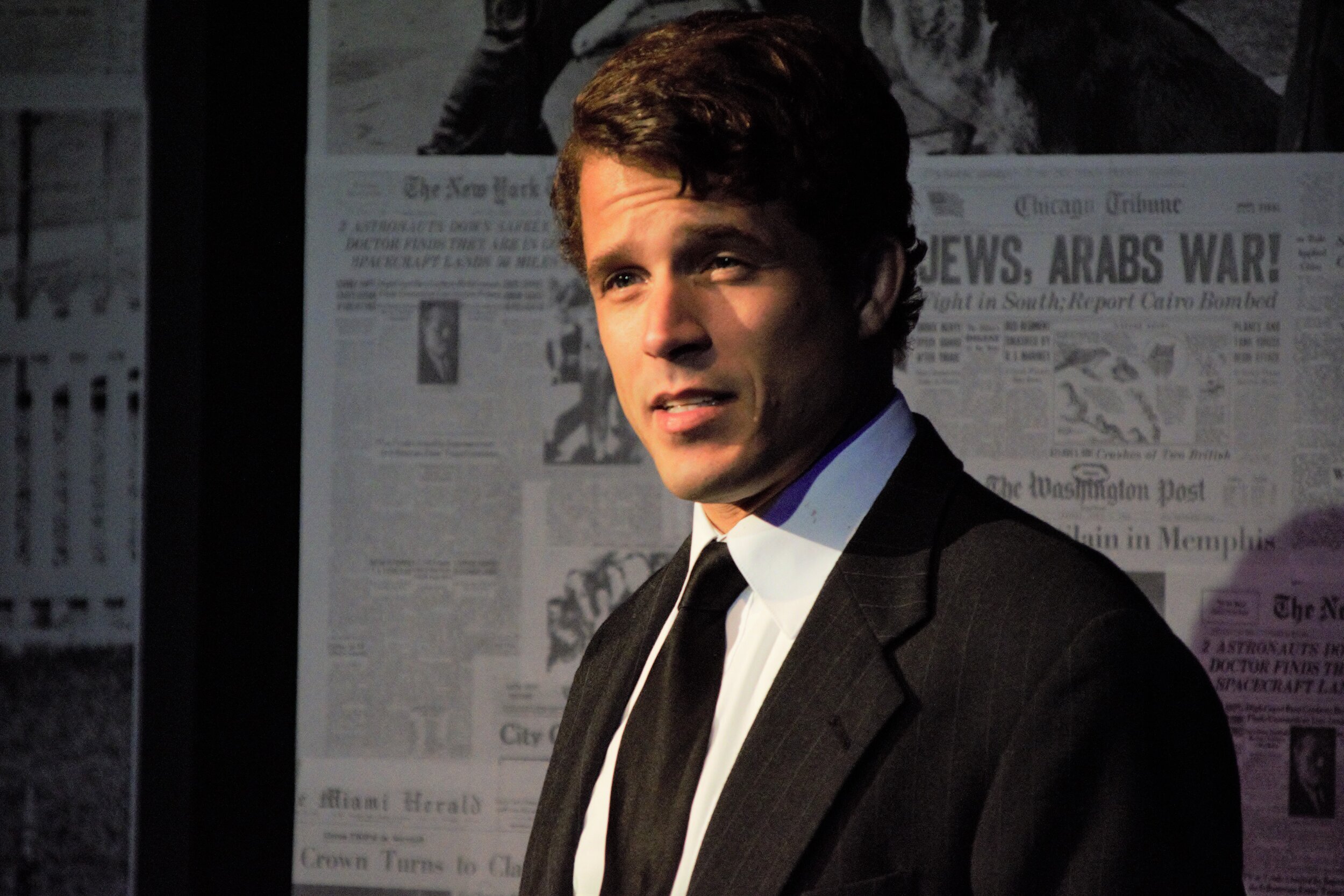

Jeff Gurner as Truman Capote in Tru, Music Theatre of Connecticut, 2021 (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Capote cut a singular figure, with an immediately recognizable voice, wispy, reedy. He was “out” before that was a generally recognized status, with long-term male partners and no effort to appear heterosexual. Capote’s affable and unflappable manner is rendered well by Jeff Gurner, who sounds like him, without parodying the manner, and, at a distance as dressed by Diane Vanderkroef, looks enough like the diminutive author to give us a facsimile of the man. The entire play takes place in Capote’s very tasteful living room in the Turtle Bay area of Manhattan (overlooking United Nations Plaza) as designed by Lindsay Fuori with prop design by Sean Sanford. Lighting design by RJ Romeo adds significant aura to moments of dramatic recollection.

Jeff Gurner as Truman Capote in Tru, Music Theatre of Connecticut, 2021 (photo by Alex Mongillo)

The play opens with Capote offended by the anonymous gift of a poinsettia and concludes when Capote, in his characteristic chapeau, dark shades, and overcoat, exits grandly for a holiday dinner with Ava Gardner and others who haven’t dropped him. Along the way, Gurner treats us to the pathos of a figure still giddy about his success and insecure about his reputation, so he must keep us enthralled by mannerism and self-quotation. At times, we feel like we’ve been summoned to an interview where we don’t get to pose the questions but must simply record the bon mots as they rain upon us.

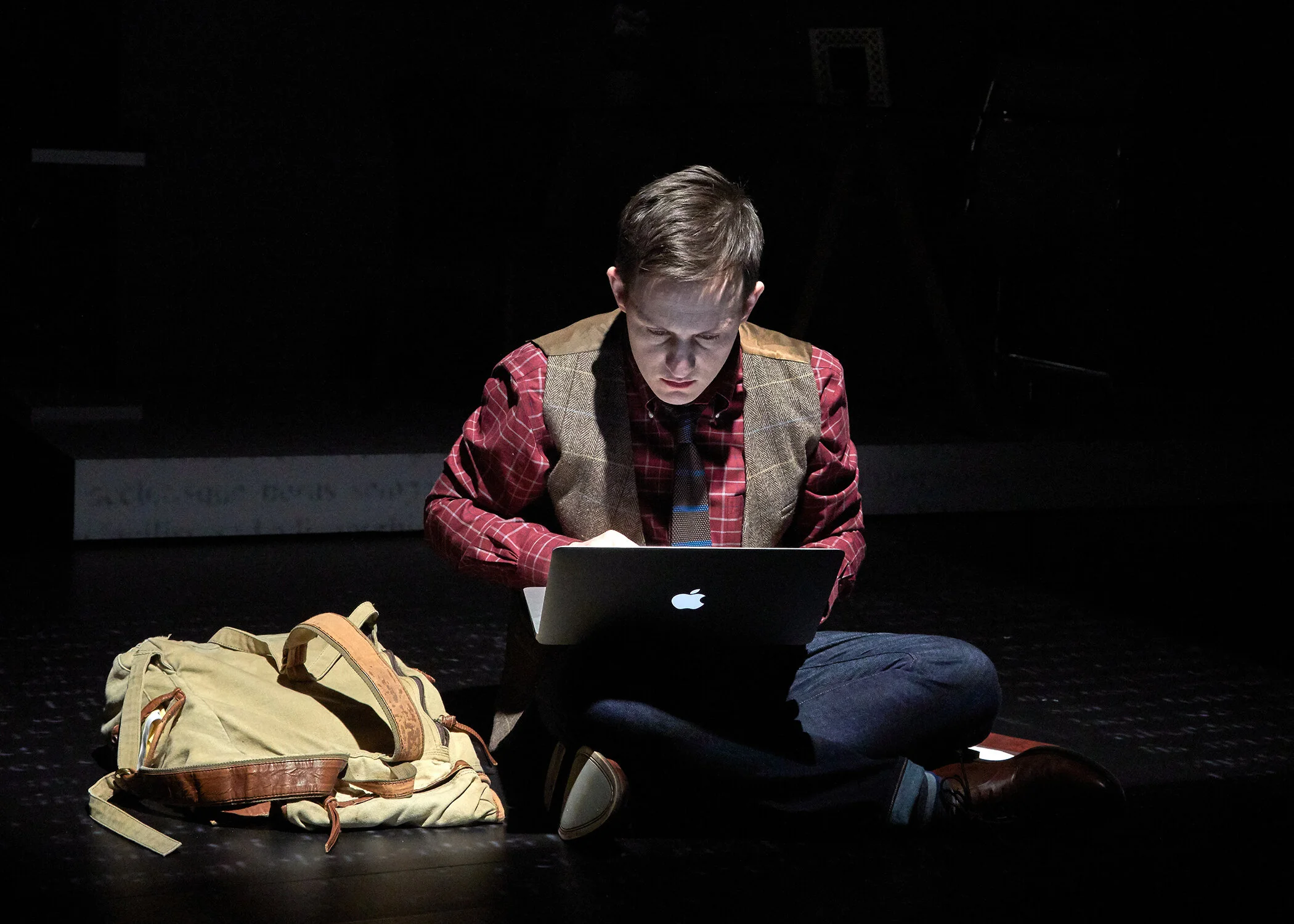

The monologue to which Capote subjects us includes moments such as his sending telegrams and engaging in telephone conversations. In these moments we sense the public Capote and that lets the tone he directs to the audience—whom he sometimes addresses as though all-too-aware that he is observed at all times—seem more private and off-the-cuff. It’s a nice distinction as Capote comes across as someone for whom life is only significant when it is shared—whether with readers, viewers, friends, hangers-on, reporters, lovers, family, enemies. The key point is that someone attends, and so, if Tru (as he’s generally known) gets bored talking to us, he can pick up a phone and let us overhear him talking to someone else.

Jeff Gurner as Truman Capote in Tru, Music Theatre of Connecticut, 2021 ( photo by Alex Mongillo)

Which of course means that Capote is a good subject for a one-person play as his manner is essentially theatrical. In the second half of the play he even does a dance routine—just to take us by surprise—and is constantly insistent on the fact that, even if he himself is not always appreciated as a performer, he has been in the presence of great performers all his life, including dancing as a child while Louis Armstrong performed and, of course, complimented him.

The point isn’t the truth, for Tru, it’s carrying off his version of things. And now he’s in hot water for not carrying off his portraits of socialites—a classic case of biting the hand that, if it doesn’t exactly feed one, at least feeds one’s vanity. And yet, for the moment, that’s all to the good because it means everyone is talking about those pieces in Esquire. And as Oscar Wilde might well remind him, “the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.” There may be something worse, though, as Capote will learn: not being spoken to. The silence that meets his efforts to reach out will drive him to more drink and drugs and more self-parodic stagings of his public persona.

Is there a moral? It’s hard to say, given that any sense of tragedy occurs, as it were, off-stage. In the play’s time-setting, Tru hasn’t yet declined. We might guess that such private theatricality, while tonic for anonymous onlookers, can be costly to the man forever in the spotlight. And yet—the play may convince us—that is Capote’s victory. He has become a character, forever larger than life and more interesting as fiction than as fact. Robert Morse earned a Tony for playing Capote in Tru on Broadway in 1990 and an Emmy for the same role in a televised version in 1992; Phillip Seymour Hoffman earned an Oscar for playing Capote in the film Capote (2005). Capote’s books have become classics and his persona a celebrated role. Perhaps nothing could be truer to Tru.

Jeff Gurner as Truman Capote in Tru, Music Theatre of Connecticut, 2021 (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Tru

Jay Presson Allen

Adapted from the works of Truman Capote

Directed by Kevin Connors

Starring Jeff Gurner as Truman Capote

Sound Design: Will Atkin; Scenic Design: Lindsay Fuori; Prop Design: Sean Sanford; Costume Design: Diane Vanderkroef; Lighting Design: RJ Romeo; Stage Manager: Jim Schilling

Music Theatre of Connecticut

April 23-May 9, 2021