Review of Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin, Westport Country Playhouse

He wrote “White Christmas” and “God Bless America” as well as an estimated 1500 other songs. Irving Berlin is one of the “household name” composers of the great American songbook. And one of the few who wrote both lyrics and melodies. Hershey Felder, who has formed a kind of theatrical cottage industry of one-man shows about famous composers—including Gershwin, Chopin and Beethoven—brings to his enactment of Berlin a warmth that makes this tour of the man’s life and music truly entertaining. The show, now playing at Westport Country Playhouse through August 3, manages to incorporate the heartbreaks in Berlin’s life without getting bogged down, creating a portrait of a unique talent who, no matter what life served up, could find his way to a tune—for a career that ran from the 1920s to the 1960s.

Berlin was born Israel Beilin, in what is now Belarus in 1898, of Jewish parents who came to this country after their town was burned down in a pogrom. The show is full of what Berlin would have known, in Yiddish, as schmaltz and chutzpah. And that’s to its credit. The story of Old World Jews making good in the new world of U.S. entertainment has a deep resonance in what people like to call “the American Dream.” That Berlin furnished two of the key theme songs of our great secular religion—in which we Americans like to worship ourselves—makes him a fitting hero in these times when pundits and politicians are so keen to assert what America really is. The chutzpah serves Berlin’s rags-to-riches climb; the schmaltz is the emotional mainstay of songs full of popular sentiment that manage not to pander, mostly.

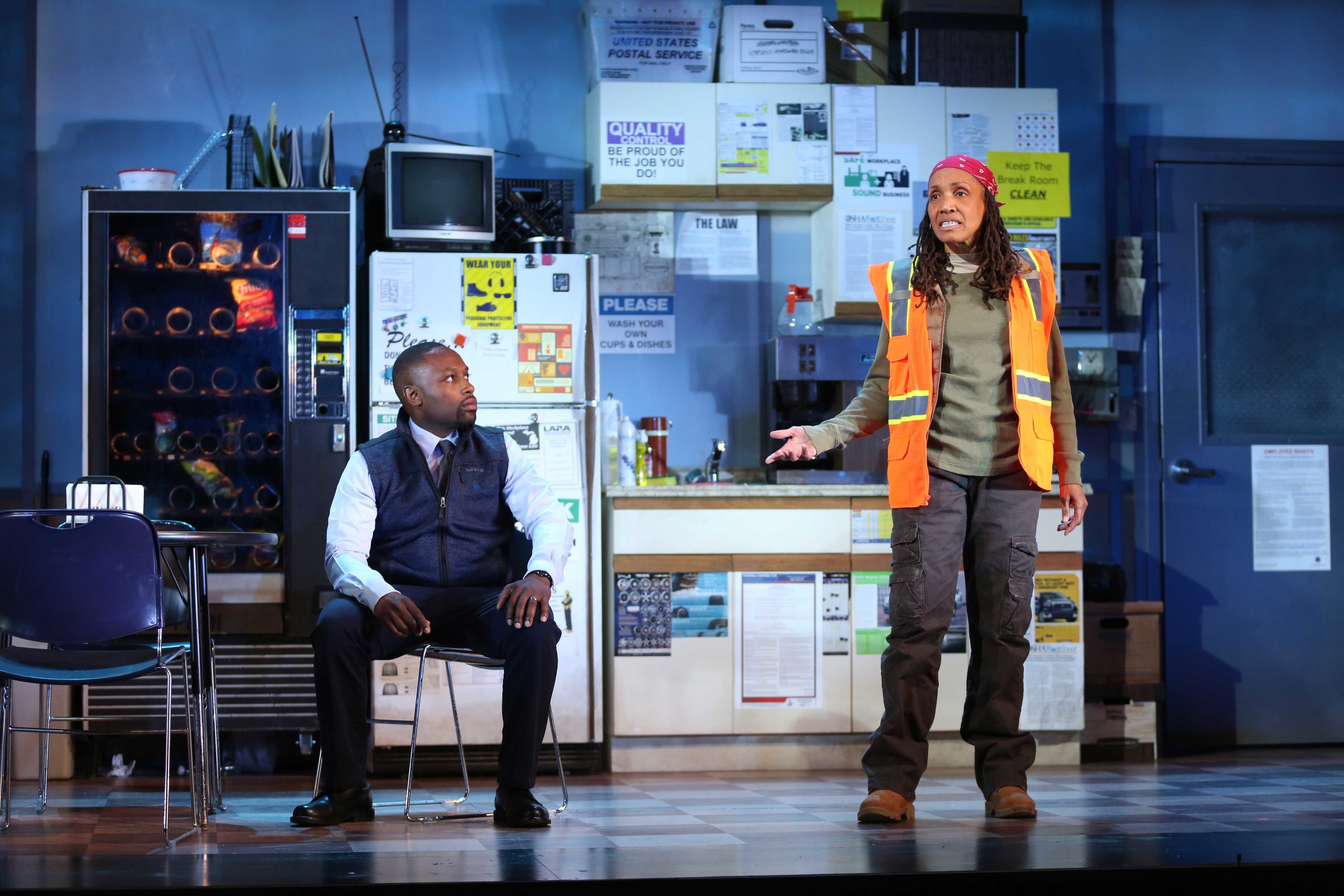

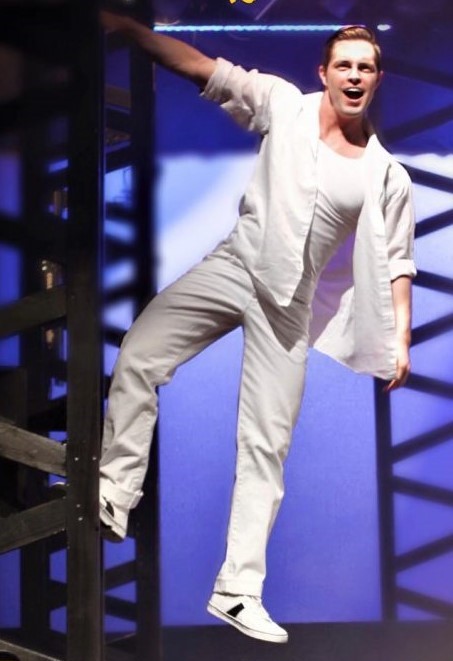

Irving Berlin (Hershey Felder) in Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin

Berlin’s story begins with the event that undermines those who would flout the part that immigration played in making twentieth-century America what it was. And he served in World War I—entertaining troops as an enlisted man—and entertained troops in World War II, as a celebrity. In other words, his immigrant origins and his patriotic bona fides can’t be denied. For both wars, Berlin wrote revues—the primary form for much of his career, a career based on his incredible knack of writing songs for any occasion. That knack began when, as a boy on the streets after his father—a trained cantor—died, he got work as a “singing waiter,” entertaining barflies with risqué lyrics to well-known songs. In the Twenties, he struck unprecedented gold with “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” a song that both tweaked the craze for ragtime and capitalized on it.

From there, as Felder shows, moving us through the years and the ups and downs, there are wonderful tunes—like “What’ll I Do” and “Always,” songs that seep nostalgia even for viewers who weren’t alive when they were hits—and there are peppy numbers that show off Berlin’s charm, like “Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” from World War 1, and, much later, “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” a song forever associated with Ethel Merman, whose ear-needling delivery Felder mimics.

Along the way there are also exemplary moments that instill in the audience the background to some familiar numbers. For instance, “God Bless America” was buried away in a drawer until its right moment came. And “White Christmas” was not only a holiday card to Berlin’s second wife, an Irish Catholic socialite, but also commemorates a personal loss. And, from As Thousands Cheer, a show in which the songs took inspiration from contemporary headlines, the great song “Suppertime” was sung by Ethel Waters as an African American wife’s lament for a lynched husband—in 1933. Felder-as-Berlin points out the times when he riled public opinion or made a bad decision—usually due to someone else’s advice.

Irving Berlin (Hershey Felder)

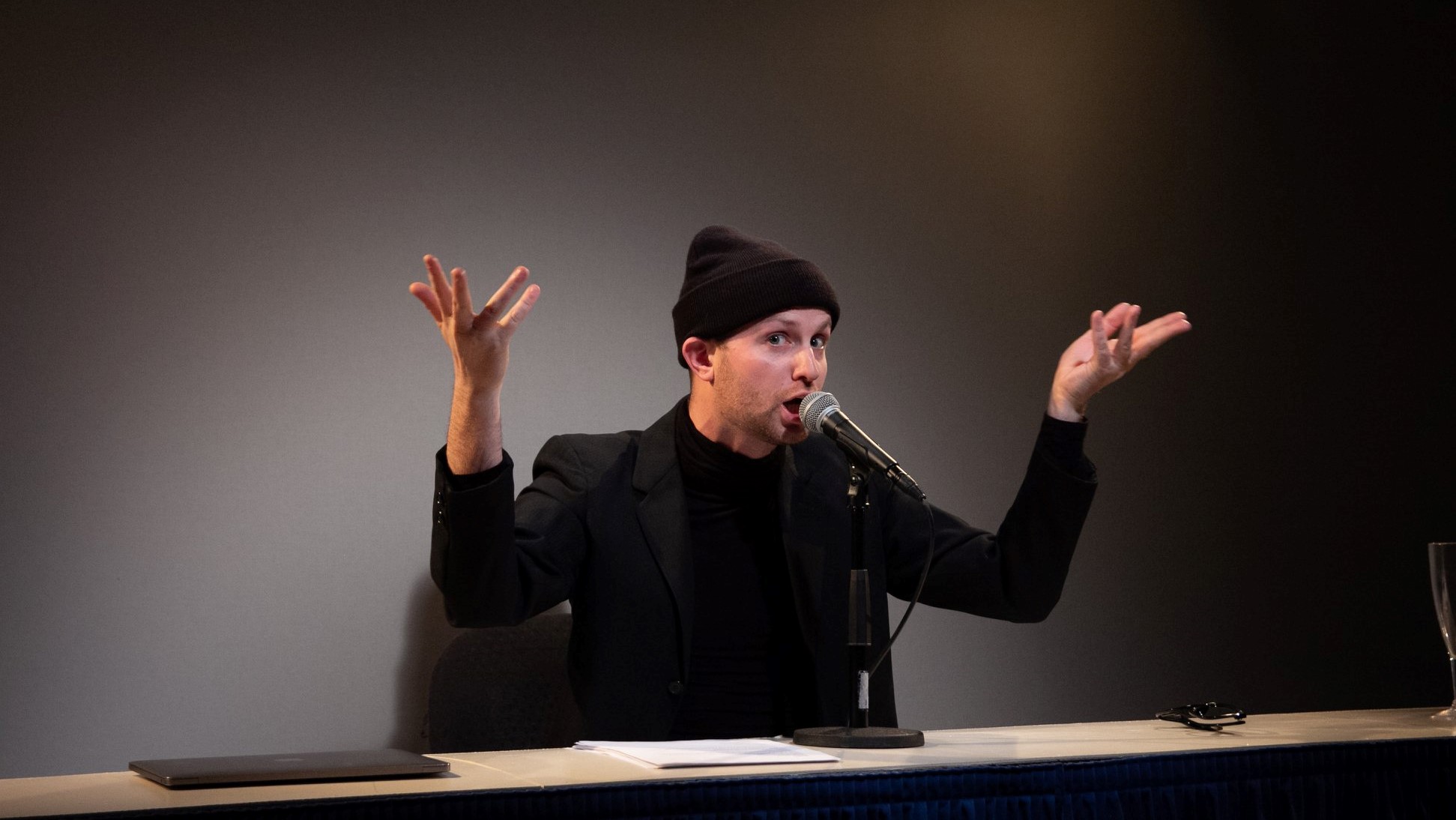

Throughout, there’s a becoming pedagogical element to the presentation, since Felder’s Berlin is all-too-aware that he’s an old fossil—the show’s opening conceit is that the audience to his 110-minute reminisce are carolers he invited into his elegant home on Beekman Place—and that understanding his career requires a history lesson. The fact that the show never quite loses momentum in the face of so much information is remarkable. Felder is well-practiced at the personable quality necessary to keep us listening, and the presentation is aided by evocative projections of photos and even footage of Al Jolson singing “Blue Skies” in The Jazz Singer, the first “talkie.”

Felder’s Berlin has the characteristic glasses, eyebrows, and hair, but Felder is a much more skilled musician than Berlin, and that lets him give a musical lesson as well, letting us see how Berlin’s sense of melody, while simple, is, at its best, distinctive. As a vocalist, Felder keeps to a delivery I assume is patterned on Berlin’s limited skills, to some extent, and as a style it serves to remind us of how dated the originals of these songs are. We hear none of the crooning that a singer like Bing Crosby brought to “White Christmas,” and one of the show’s more effective devices is using audience sing-along participation to demonstrate that not only are Berlin’s songs well known, they have been learned “by heart.”

Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin

As a quick intro to a formidable talent, the show has much to recommend it, and as a theatrical device that lets us consider the skill of wartime entertainments, the struggle in the lives of immigrants, the competitiveness of show biz and the luck and persistence, the personal resonance in any artist’s relation to his own work, and the sprawling effort, over the decades, to remain true to what America wants, Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin lets us feel the stirring identification that comes with being audience to a great career lovingly evoked.

Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin

Music and Lyrics by Irving Berlin

Book by Hershey Felder

Directed by Trevor Hay

Starring Hershey Felder

Consulting Producer: Joel Zwick; Lighting Design: Richard Norwood; Projection Co-Design: Christopher Ash; Projection Co-Design: Lawrence Siefert; Sound Designer/Production Manager: Erik Cartensen; Costume & Scenic Artist: Stacey Nezda; Historical and Biographical Research: Meghan Maiya; Producer: Eva Price

Westport Country Playhouse

July 16-August 3, 2019