Review of Doubt: A Parable, Westport Country Playhouse

John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: A Parable, the second offering of Westport Country Playhouse’s two-show mini-season runs in-person until November 20, with a streaming version of the play available online from November 11 to November 21. This is the first live production at the venerable venue since the COVID shutdowns and the last until the playhouse’s next full season opens in April 2022 (for information on the latter, see below).

Directed by David Kennedy, WCP’s associate artistic director, the current production of Doubt—which won a Pulitzer and the Tony for Best Play 2005—provides an interesting example of how context can affect a play. Back in 2005, the play was a timely fictionalization of issues that arose out of the Boston Globe’s celebrated 2002 exposure of child-abuse among Catholic priests. The investigations did indeed reveal abuse and cover-ups dating back decades, and yet Shanley’s play, set in 1964, can still feel anachronistic in the way it portrays characters who seem to live with an open secret.

Now, almost twenty years later, Shanley’s “parable” gains by not riding the coattails of a major news story. The questions the play aims to raise—about doubt and certainty—move into a more parabolic realm less concerned with the times and more readily timeless. And that helps to foreground what has always been the play’s greatest strength: that it can be staged to have very different effects without changing a single word. The notion that the play’s final act takes place offstage—in the conversations of its audience members—still holds true. I’ve seen the play staged once before and can say that the take-aways from the two productions were markedly different.

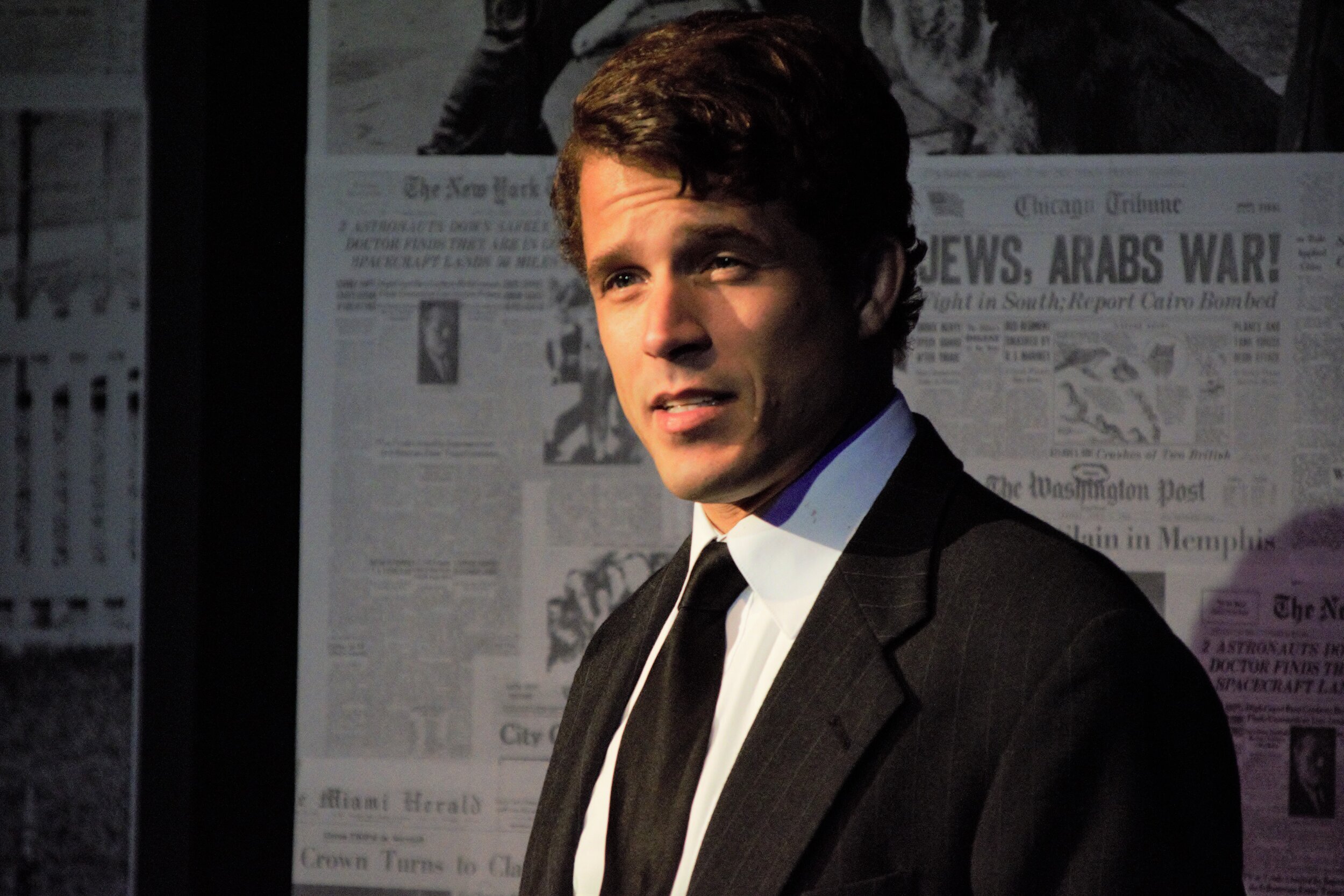

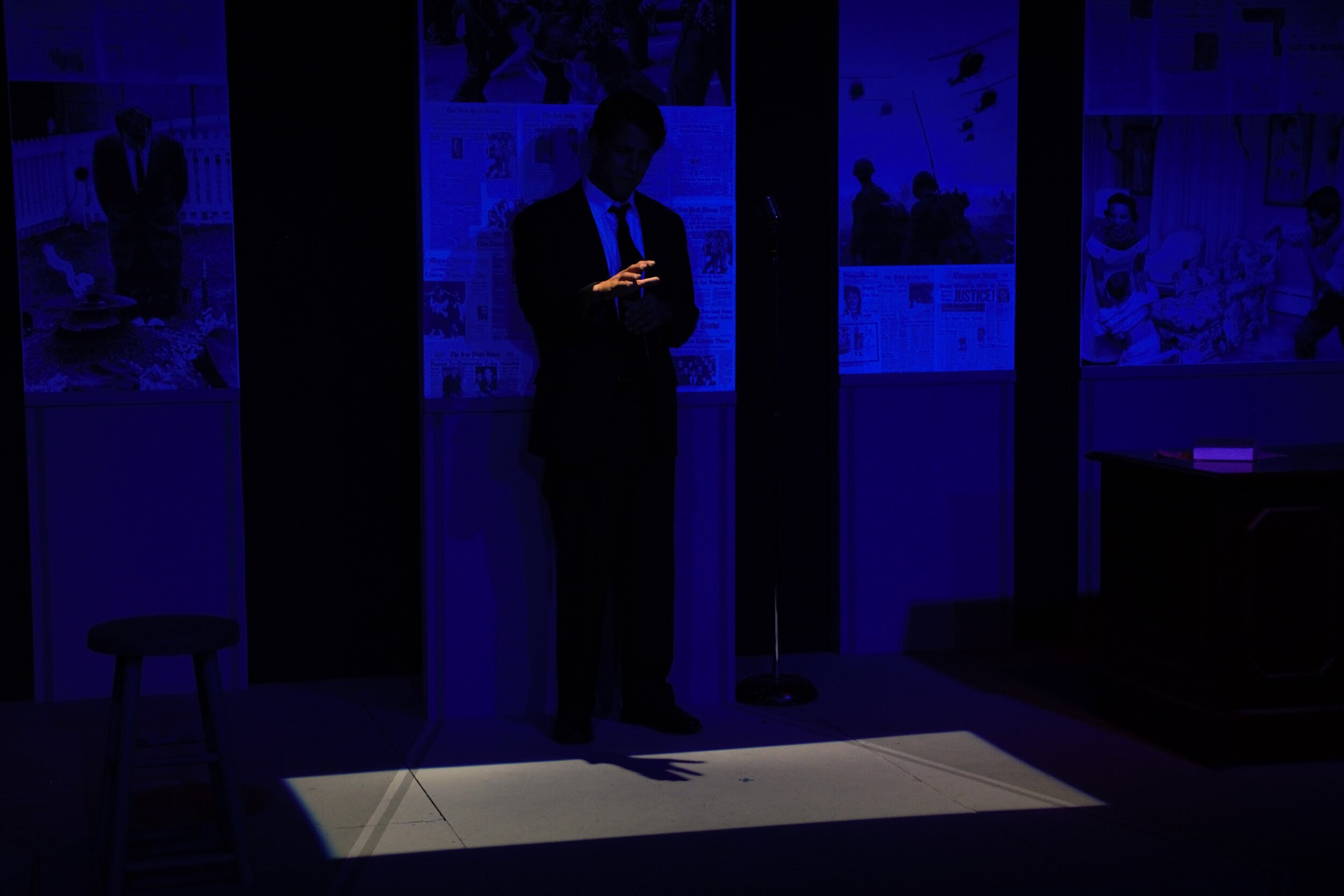

Sister Aloysius (Betsy Aidem) and Father Flynn (Erik Bryant) in the Westport Country Playhouse production of Doubt: A Parable; photo by Carol Rosegg

The story concerns the efforts of Sister Aloysius (Betsy Aidem), principal at a Catholic school in the Bronx, to remove Father Flynn (Eric Bryant) from his position in the parish due to her belief that he has seduced or is attempting to seduce a young boy, Donald Muller, the first and only African American child at the school. To this end, Sister Aloysius enlists the aid of Sister James (Kerstin Anderson) to help make a case to be taken to their superiors. Father Flynn, ambushed in a meeting with the two nuns, later turns to Sister James to give his view of the situation. But a surprising interview between Sister Aloysius and the boy’s mother (Sharina Martin) seems to strengthen the principal’s resolve.

Sister James (Kerstin Anderson) and Sister Aloysius (Betsy Aidem) in the Westport Country Playhouse production of Doubt: A Parable; photo by Carol Rosegg

Sister Aloysius is portrayed as rigidly old guard—down on secular songs in Christmas pageants, on ballpoint pens, on teachers as “friends” to their students, and certainly on the touchy-feely version of mentoring that Father Flynn prefers. There’s not a lot that can be done with her character as she’s not meant to be sympathetic even if we might grant her a certain steely charm. Betsy Aidem’s portrayal captures well the kind of personal authority that those with rigid parameters for what’s allowed and what’s not can steep themselves in. And Kerstin Anderson establishes well the conflicts in Sister James: by temperament, she is sympathetic to Father Flynn; by the hierarchy of her order, she should support Sister Aloysius. Particularly if the elder nun is correct in her assumptions. But if she’s wrong? That doubt makes Sister James somewhat our stand-in, trying to decide between these two opponents, both practiced at getting others to do what they want them to do. For their own good.

It’s in the character of Father Flynn that the play offers the most potential for varied interpretations. He could be more openly arrogant, feeling that he’s above any criticism, he could be genuinely aghast at the suspicions in Sister A’s mind, or he could be a serial abuser trying to cover his tracks. Bryant’s Flynn downplays the arrogance, trying hard for a bid for sympathy from his opponent. How much sympathy he earns from the viewer is for each to decide.

Aloysius is open about her dislike of Flynn and there’s little point in considering ulterior motives: she sees him and his tendencies as pastor—even if he is innocent of abuse—as inimical to her view of how the Church should present itself. But if she’s wrong about Flynn’s infractions, then she’s simply using suspicion to taint his reputation and to drive him out. The power-play aspects of Shanley’s script strike me as its most enduring element. The fact that we can’t really know is the core of what the play offers as its insight into human relations. How do we assess someone else’s character? By what they do, by what they say, but what about what they don’t openly say or do? The value of doubt is that it reminds us human behavior is mostly lacking in absolutes. There’s always a little wiggle room.

At Westport, Kennedy’s production highlights the emotions, with the two central characters breaking down and collapsing to the floor at different moments. While her outburst may make Sister Aloysius more sympathetic in the end, Father Flynn’s outburst has the opposite effect. Arguably, his attempt to play on emotions makes him seem more guilty, or at least seems to indicate he may be culpable even if only for his thoughts or intentions.

Mrs. Muller (Sharina Martin) and Sister Aloysius (Betsy Aidem) in The Westport Country Playhouse production of Doubt: A Parable; photo by Carol Rosegg

A key scene is the discussion of Donald’s situation between Sister Aloysius and Mrs. Muller. In a way, Mrs. Muller’s view—which Sharina Martin registers as a hard truth arrived at through experience—serves best to put the priest’s interest in the boy in a context not as dark as the one Sister Aloysius assumes; in any case, Flynn may help the boy, but, in Sister Aloysius’ view, only at great risk.

Once again director David Kennedy delivers a play in which complex issues and implications are presented through well-orchestrated dialogues. While not having quite the drama of others he’s directed—like The Invisible Hand or Appropriate—or the comedy of The Understudy, Doubt acquires great power from its perfect pacing and by demonstrating that doubt and certainty can be equally unnerving.

Doubt: A Parable

By John Patrick Shanley

Directed by David Kennedy

Scenic Designer: Charlie Corcoran; Costume Designer: Sarita Fellows; Lighting Designer: Carolina Ortiz Herrera; Sound Designer: Fred Kennedy; Production Dramaturg: Dana Tanner-Kennedy; Production Stage Manager: Shane Schnetzer

Cast: Betsy Aidem; Kerstin Anderson; Erik Bryant; Sharina Martin

Westport Country Playhouse

In person: November 2-20, 2021

Streaming: November 11-21, 2021

On sale now are ticket packages for the 2022 season:

Next to Normal

Music by Tom Kitt

Book and Lyrics by Brian Yorkey

Directed and choreographed by Marcos Santana

The 2009 Tony-winning musical and winner of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Drama: musical theater that looks at a family in crisis with introspective songs.

April 5-23, 2002

Straight White Men

By Young Jean Lee

Directed by Mark Lamos

A father and two grown sons “forced to face their own identities” in inventive playwright Young Jean Lee’s 2014 play.

May 24-June 11, 2022

Ain’t Misbehavin’

Conceived by Richard Maltby, Jr. and Murray Horwitz

Directed and choreographed by Camille A. Brown

The 1978 Tony winner—“a dance-filled and reimagined celebration of jazz great Fats Waller,” from Camille A. Brown, recently awarded and nominated for her work on for colored girls.

July 5-23, 2022

4000 Miles

By Amy Herzog

Directed by David Kennedy

An intergenerational comedy from Amy Herzog—in which a 21-year-old visits his 91-year-old grandmother; a wry and wise Pulitzer finalist from 2013.

August 23-September 10, 2022

From the Mississippi Delta

By Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland

An autobiographical play using story, song and memories to dramatize a harrowing and inspiring journey from a childhood in poverty in Mississippi to the civil rights movement and the life of a professor.

October 18-November 5, 2022