Review of Ain’t Misbehavin’, Westport Country Playhouse

“We’re about to make a joyful noise,” said Mark Lamos, Artistic Director of Westport Country Playhouse, kicking off the opening night performance of Ain’t Misbehavin’, a showcase of Fats Waller’s music conceived by Richard Maltby Jr. and Murray Horwitz. The production was slated to appear pre-pandemic and is now having its moment, in a co-production with Barrington Stage and Geva Theatre Center. And the joy of finally staging this production of energetic and vibrant versions of some of the best from legendary pianist / performer / composer Waller’s songbook is this show’s main strength.

The cast and the band of Ain’t Misbehavin’ at Westport Country Playhouse, directed by Jeffrey L. Page (photo by Ron Heerkens, Jr.)

In 2022, director and choreographer Jeffrey L. Page reconceived the musical, first produced in 1978, so that it engages with aspects of Black American identity as both performance and protest. While the musical artistry of Waller’s songs are never in question—and hearing a live band play them is a delight that increases as the night goes on—the role of the singer of a Waller song, particularly on a dramatic stage, is more open to debate. Musical it must be, but the performance also has to enact both the song’s lyrics and something of its context. While the performances are enthusiastic, the show’s dramatic artistry registers more strongly in the second act. The first act primarily acquaints us with the performers, but since there is no overarching story to convey, each song is more or less it’s own thing, bound together by the delights of Waller’s stride piano. The choreography impresses most on the big numbers, like “The Jitterbug Waltz,” a highpoint of Act 1, with its overlapping vocals and dancing couples. In the early going the show’s ambiance would’ve benefited from a bit more saloon, less Broadway revue. The aura of a late night joint became more prevalent in the second half.

Judith Franklin, Paris Bennett, Miya Bass in Ain’t Misbehavin’ at Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Ron Heerkens, Jr.)

Throughout there are foot-tapping set pieces aplenty—from the big production numbers, like the opening title song, or “The Joint is Jumpin’,” where cast members imitate musical instruments, or, early in the second Act, the brightly arch “Lounging at the Waldorf,” where the cast sports a costume change that has them stepping out, dressed to the hilt.

The cast of Ain’t Misbehavin’ at Westport Country Playhouse, directed by Jeffrey L. Page (photo by Ron Heerkens, Jr.)

Another Act I set piece involves staging as if for a performance during World War 2, so that the antiquated songs—"Yacht Club Swing,” “When the Nylons Bloom Again,” “Cash for Your Trash”—all register as timely songs in which Waller invigorates the era, adding swing to the straitened circumstances (Waller himself died of pneumonia while traveling during wartime). The spirit of Waller as a showman, with his tongue-in-cheek grasp of how to proclaim the special status of his own particular blues, is well served by some of his best numbers: “Lookin’ Good But Feelin’ Bad,” “’T Ain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do,” “Handful of Keys,” while others showcase the tit for tat of difficult relations: “Mean to Me,” “That Ain’t Right,” “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now,” or, one of Waller’s best, the joys of the playful torch song, “Honeysuckle Rose”—here a duet between Paris Bennett and Will Stone.

Jay Copeland and Will Stone in Ain’t Misbehavin’, Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Ron Heerkens, Jr.)

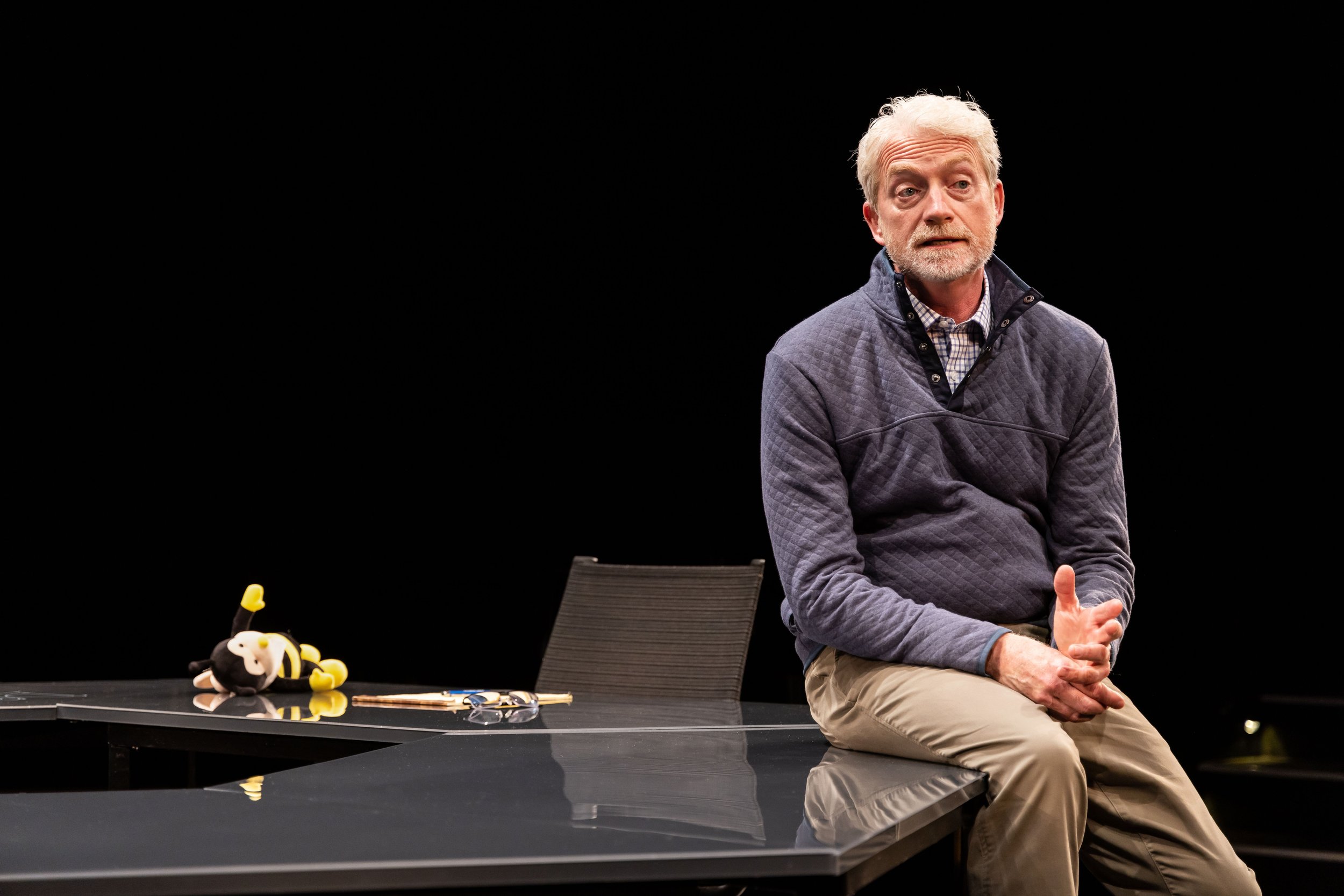

In the second act, the skills of Will Stone and Jay Copeland come to the fore. Copeland slinks his way through a bravura “The Viper’s Drag/The Reefer Song” that goes a long way to both instantiate and interrogate the subtext that Waller’s music is always winking at: how to be a harmless Black for the White folks and how to be a canny showman to his Black audiences. Waller, with his incredibly mobile face and comic timing, tended to clown it up—a tradition to which Stone does full justice with his drunken lout in “Your Feet’s Too Big,” and, with Copeland, as a minstrel duo in “Fat and Greasy.” The fun of the number fades when the duo freeze as though caught in problematic roles. The next number, featuring the entire cast, is “Black and Blue,” a rare, direct confrontation of racial difference in Waller’s work. And with that, the show finally arrives at its fullest statement.

The cast of Ain’t Misbehavin’ at Westport Country Playhouse, directed by Jeffrey L. Page (photo by Ron Heerkens, Jr.)

The final numbers take us back to Fats Waller as the kind of showman more apt to unite audiences than divide them, his talent, skill, love of performance and sheer musical genius keep these songs alive and end the evening with high spirits.

Ain’t Misbehavin’

The Fats Waller Musical Show

Conceived by Richard Maltby, Jr. and Murray Horwitz

Directed and Choreographed by Jeffrey L. Page

A Co-production with Barrington Stage and Geva Theatre Center

Scenic Design: Raul Abrego; Costume Design: Oana Botez; Lighting Design: Philip Rosenberg; Sound Design: Leon Rosenberg; Music Director: Terry Bogart; Associate Director/Choreographer: Fritzlyn Hector; Props Supervisor: Sean Sanford; Production Stage Manager: Alexis Nalbandian; Assistant Stage Manager: Tré Wheeler

Cast: Miya Bass, Paris Bennett, Jay Copeland, Judith Franklin, Will Stone

Musicians: Terry Bogart, piano/music director; Donavan Austin, trombone; Jason Clotter, bass; Bernell Jones II, reed 2 clarinet/tenor saxophone; Kevin Oliver, reed 1 clarinet/alto saxophone; Ryan Sands, drums; John Williams II, trumpet

Westport Country Playhouse

April 11-April 29, 2023