For Sara Holdren, artistic director of the Yale Summer Cabaret, 2015, and director of its final show of the summer, opening tonight, Orlando, above all, requires fluidity. Adapted by Sarah Ruhl from Virginia Woolf’s novel, the play should feel like “a stopper was pulled and rushing waters are flowing like a river.” In thinking of the play during the course of the summer, Holdren says, she began “to really feel like the play is a dance.” In talks with her design team, she has come back again and again to a notion of how spare and simple the set and costuming should be. “Even the actors’ bodies should be like abstract elements.”

This summer’s Cabaret has been strong in physical theater, with varied and inventive improvisations worked upon Shakespeare’s plays, particularly A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus, while the second show of the season, love holds a lamp in this little room, was entirely devised by its cast and director Leora Morris. Orlando is the only play this season with a pre-existing script, and, while that might suggest something a bit more straight-forward, Holdren insists that “physical storytelling” is very much the goal. For inspiration, she gave the cast of seven—Melanie Field, Leland Fowler, Chalia La Tour, Niall Powderly, Elizabeth Stahlmann, Josephine Stewart, Shaunette Renée Wilson—“The Storyteller,” an essay by Walter Benjamin that stresses how the oral storytelling tradition, being lost in the era of print, was a matter of gesture, combining hand, eye, soul.

That view suits Ruhl’s play, Holdren says, because the script is all from Woolf’s novel, cut-up and arranged. For Holdren, “all along, a key attraction of the play is the fact that it is narrated.” While for some that very fact sins against the “show don’t tell” mantra that drives much storytelling, the challenge of dramatizing the telling is intrinsic to Holdren’s view of the play. It helps that Ruhl’s play is very unfixed in how it assigns text to character. That leads, in Holdren’s phrase, “to the strange and fortuitous assignment of parts,” based on what the actors do in rehearsal with the voices of the chorus. Much is a matter of gesture indeed.

“Rather than work with a facsimile of a depicted world, Orlando works with the world of telling,” Holdren says, and that world is one that moves from Elizabethan times to post-World War I as narrated by a seemingly ageless protagonist who also alters gender from male to female. The presence of the narrating Orlando, played by Stahlmann, might make the play seem like a tall tale, a story of magical changes and wonders that correspond to the character’s self-conceptions. Orlando is, after all, a poet, and his/her literary efforts are signified by a set shaped like a blank page. What Orlando is writing is, in a sense, both the novel and the play, but, at the same time, the events she experiences are shaping what will be written.

For Holdren and her Rough Magic company this summer, much wonderful theater has come from a similar approach: finding the play through enactment, where the experience of working on the play produces the play. As Holdren points out, even Stanislavski, best known in the U.S. as the theorist behind “the method” school of acting, valued improvisation and allowed that the work of theater could precede text. “Truth on stage,” Holdren says, needn’t be “character-based” in the sense of revealing a consistent psychological portrait. The shows at the Cabaret this summer have been strong in fluid characters changing before our eyes, and with that comes, in Holdren’s view, the possibility of transformation as key to the theatrical experience.

The season has looked at how magic and wonder can be expressed in the telling, in enacting—as with the bewitched actors in Midsummer, or the five enactments of “the Menken” in love holds a lamp in this little room, or the shifting roles of the tripartite Mephisto in Dr. Faustus—the multiplicity of identity. At the same time, all the plays this summer, even if not tragic like Faustus, have kept in touch with a darker side, what Holdren, in speaking of Orlando, calls “death moments.”

At the run-through rehearsal I attended, I could see what she meant. In the character of Woolf herself—as the author behind the narrator—there is a certain element of depression, of finding history and the rigors of either gender not to her liking. She is able to align that element of her own nature with the melancholy that has been fashionable for poetic souls at least since Elizabethan times, and Ruhl’s play and Holdren’s production pick up on that. But, as with all the plays this summer, there is also much fun with the “amorphous multiverse” of theatrical conceptions.

And yet, for all the playfulness of their theatrical conceits, the plays of the Rough Magic season have revealed—in dueling fairies casting spells in strife and in actors shocked by what their playacting reveals of themselves, in the subterfuges by which a consummate performer may divert her audience and deceive herself, in the quest for a kind of immortality that ends in a humbling of vanity—that the spell theater casts is not without its dangers and its discomforts. Orlando celebrates the wit required to endure through the ages, but at the cost, perhaps, of being equal to a particular age. Or as Orlando’s (initial) contemporary might say, “Lord, we know what we are, but not what we may be.”

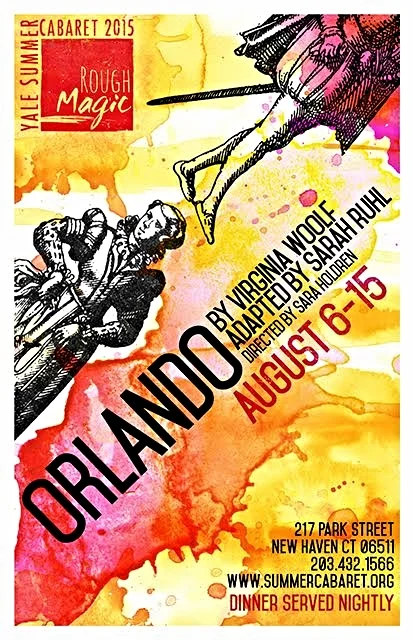

Orlando

By Sarah Ruhl, adapted from the novel by Viriginia Woolf

Directed by Sara Holdren

Yale Summer Cabaret, August 6-15, 2015