Review of Orlando at Yale Summer Cabaret

Orlando, the final show of the Yale Summer Cabaret season, directed by artistic director Sara Holdren, presents the kind of frenetic, improvisatory work that has been a hallmark of the season. But this time, the only devised aspect is the staging. The script is by Sarah Ruhl, from Virginia Woolf’s novel, untampered with by the Rough Magic Company. Having seen the company have its way with Shakespeare and Marlowe, we might wonder if other takes on Woolf’s text might present themselves, which is a way of asking, I suppose: how successful is Orlando as a play? Prose stylists like Woolf might be said to be best in their own element: on the page.

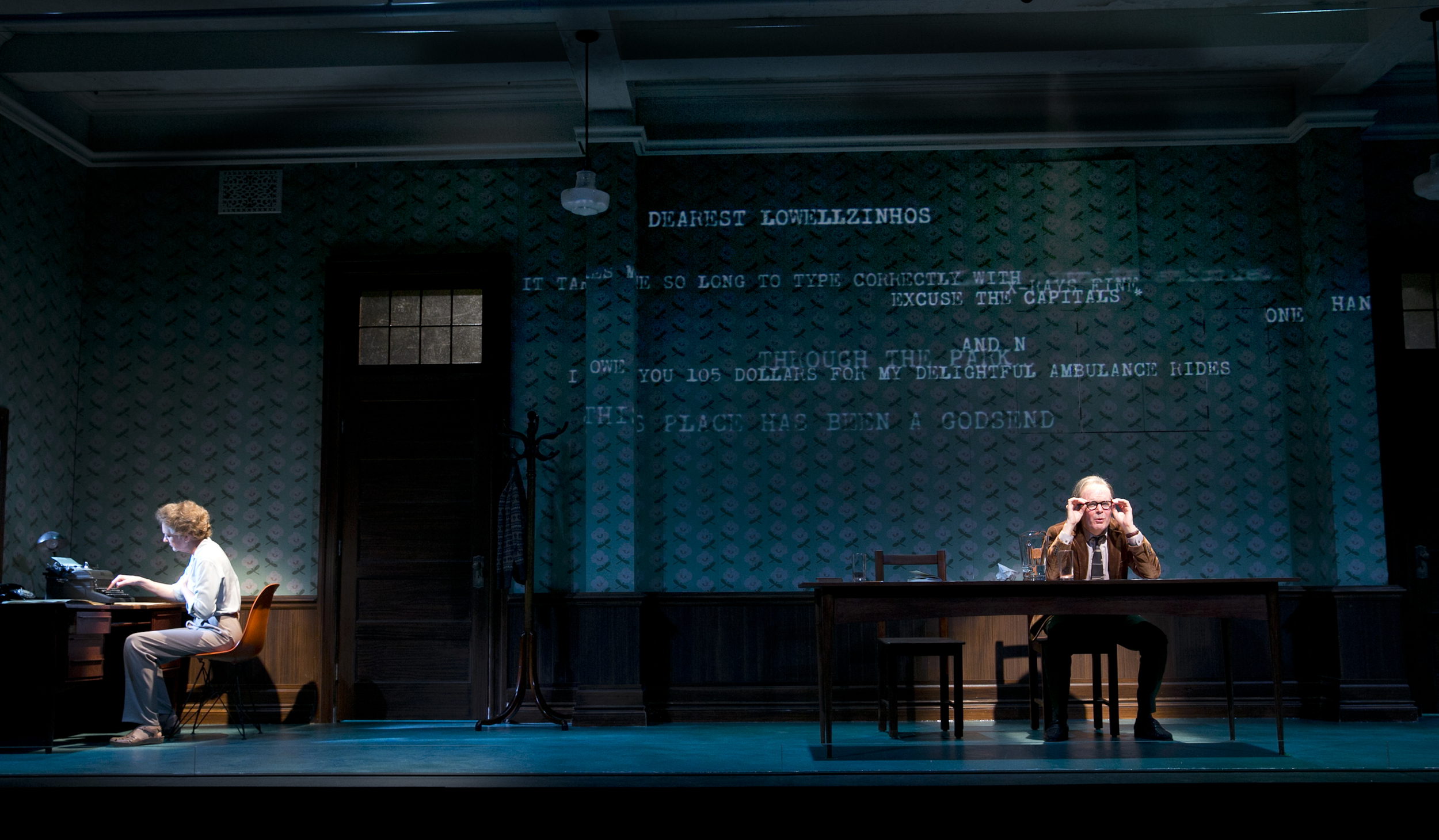

Joey Moro’s set takes note of that thought by offering us a long scroll upon which the players cavort as though, literally or literarily, on the page. And that’s as it should be since, as the play goes on, we find ourselves wondering what is “real” and what is merely the fantasy of a would-be poet—Orlando (Elizabeth Stahlmann)—an Elizabethan nobleman seated in the garden of his great estate and dreaming the world and the life to come. A life in which, at age 30 (and the dawn of the 19th century), he becomes a woman.

Much of the brio of Woolf’s novel is in the rendering of a fantasy of the English past from the present (the 1920s), viewing the past with the prescience of the future. The conceit makes for an interesting hybrid interplay—between the past we invent and the past as it was—that Ruhl’s play maintains effectively. The difficulty comes from the fact that Woolf never set herself to write “characters” per se (all are “charactered in the brain” of Orlando); Ruhl gets around this by creating a chorus who can alter as necessary, through the scenes and through the ages.

The cast of Orlando: Josephine Stewart, Shaunette Renee Wilson, Niall Powderly, Elizabeth Stahlmann, Chalia La Tour, Melanie Field, Leland Fowler

That makes for much of the fun here as the staging and costume work is comical, inventive, breathless. My favorite moment features Orlando in a kind of Elizabethan fetish costume (the ruff, the rosettes, the pantaloons) twirling about on a hanging hoop (viewers of Holdren’s fascinating thesis show will recall her work with gymnast-actors) with Sasha (Chalia La Tour, one of the most chameleonic actors currently at the Drama School) in a graceful white cape and white fur cap. Sasha is the best secondary character in the play, if only because La Tour makes her as real as Orlando is. She could easily take over the play, since Orlando sees that she’s way more fascinating than he.

The other characters that interact with Orlando seem more brainspun: Melanie Field has fun with a motorized Queen Elizabeth, a dowager who dotes on a fine leg in tights, and gives our hero a bawdy lesson in a courtier’s duties. Niall Powderly does all he can to make a cross-dressing Romanian count/countess as ridiculous as possible, including an outrageous accent that would do Tim Curry proud. Leland Fowler plays the Byronic Shelmerdine pretty much as written—which is to say that we begin to suspect that Woolf might be fantasizing life in an Emily Brontë novel or as Mary Shelley. Till then, the point has been made, it’s much more exciting—in Orlando’s view—to pursue a female than to be pursued as one. Unfortunately, Shelmerdine, though he receives the accolade of making Lady Orlando feel “a real woman,” might be any well-spoken, well-born hero of many a romance novel, though for Woolf, writing under the spell of Vita Sackville-West, the meeting of soul mates requires that both Orlando and Shelmerdine imagine they are in a same-sex relationship.

Front: Elizabeth Stahlmann, Niall Powderly; Back: Melanie Field, Chalia La Tour, Leland Fowler, Shaunette Renee Wilson

Ruhl and Woolf take delight in satirizing the ubiquity of marriage, a target that never seems to go out of date, though—in same sex, soulmate terms—it has taken on, in our time, more possibilities than it had for Woolf in the ‘20s. And that’s what helps make Orlando interesting as theater: even more than on the page, we feel the spin through the years (costumes by Fabian Aguilar and Haydee Zelideth are great aids in the fantasia), and we’re even more aware of how the all-important “present moment” infuses our viewing and our experience.

Ultimately, Ruhl’s Orlando “longs to be only one thing” while Holdren’s production, and the mutable Rough Magic company in general, suggests that playing only one character with one gender is a tired approach to theater. In Orlando, Holdren and company find an ideal text for the transformations they’ve played with all summer. And yet, Orlando strikes me as what used to be called “closet drama”—a play to be read and imagined. We become aware of how hard it is to playact Woolfian fictions. Nimble as the Rough Magic troupe is in bringing the play to life on stage, they can at best only approximate the unfettered flight of the poetical mind, as Ruhl’s Orlando only suggests Woolf’s.

Front: Elizabeth Stahlmann as Orlando; Back: Shaunette Renee Wilson, Josephine Stewart, Chalia La Tour, Leland Fowler

Casting only one actor as Orlando brings home the fact that a story, no matter how variously conceived, must always be the story of someone. Stahlmann plays Orlando as if each moment is a new thought, full of fresh insight into what life can offer. She achieves the gusto of the Keatsean ideal of the poetical character (“it is not itself - it has no self – it is everything and nothing – It has no character […] it lives in gusto”), but that makes for a passive hero always amazed at what is happening, much as we are in dreams.

Finally, though, to this production’s credit, Stahlmann makes us feel, more than fiction can, the cost of such flights from one’s time; her Orlando suffers before our eyes as only intensely imagined characters do. In the end, being one thing means being a thing that will end.

Orlando

By Virginia Woolf / Adapted by Sarah Ruhl

Directed by Sara Holdren

Scenic Design: Joey Moro; Costume Design: Haydee Zelideth & Fabian Aguilar; Lighting Design: Andrew Griffin; Sound Design: Kate Marvin; Projection Design: Joey Moro; Dramaturg: Rachel Carpman; Stage Manager: Emely Zepeda; Photographs: Andrea H. Berman

Ensemble: Orlando: Elizabeth Stahlmann; Chorus: Melanie Field, Leland Fowler, Chalia La Tour, Niall Powderly, Josephine Stewart, Shaunette Renée Wilson

Yale Summer Cabaret

August 6-15, 2015