Review of The Moors at Yale Repertory Theatre

Jen Silverman’s The Moors, directed by Jackson Gay, at the Yale Repertory Theatre, is brilliant stuff. The play revisits the familiar tropes of Gothic fiction with a sharp sense of the absurd: the sweet and well-meaning governess summoned to a grand manor house on the desolate moors; the peremptory lady of the house, the mysterious master of the estate—her brother; another sister, who pines after literary fame; the surly menial who no doubt knows more than she says, and who may be “with child” or with typhus, or both. Into such a fraught setting, which might do well as the basis for campy comedy or a revisiting of melodrama, Silverman drops dialogue that feels bracingly contemporary, with traces of Beckett and Stoppard. Which is to say that the lines are acerbic, funny, and tend to ride the play’s quizzical rhythms like a moor-hen on a stiff breeze.

The cast of The Moors

One of the most successful conceits here is a philosophical dog, a morose Mastiff (Jeff Biehl) who eventually becomes fixated on a charming but flighty Moor-Hen (Jessica Love). Pet of the late parson, the sisters’ father, the Mastiff wants to encounter God and takes the Moor-Hen to be an emissary from the supreme being. Their exchanges have a kind of elemental purity that makes us aware of how queasy speech is as a means to arrive at any kind of understanding. As different species, the Mastiff and Moor-Hen cannot share a world view any more than they can mate. But Silverman makes them emblematic of the more alarming aspects of attachment, particularly the hopeless or domineering variety.

A Moor-Hen (Jessica Love), The Mastiff (Jeff Biehl)

The attachments on display among the humans also depend upon negotiations with certain possibilities in language, and it is attention to language that makes The Moors such a well-crafted delight. Cold and rigorous Agatha (Kelly McAndrew) might be called “manly” in terms of the times, but she’s also a woman who knows her own mind; she tells the simpering governess, Emilie (Miriam Silverman), “you have been handed limitations, which you accepted.” As unlikely as she may be as a mentor, Agatha manages to seduce the governess in part by means of the letters that brought Emilie to the manor, written as though in the hand of master Branwell, Agatha's brother. The two enact a mistress/maid relationship that makes manifest the kind of sexual dynamic that tends to lurk more latent in typical Gothic fiction.

Emilie (Miriam Silverman), Agatha (Kelly McAndrew)

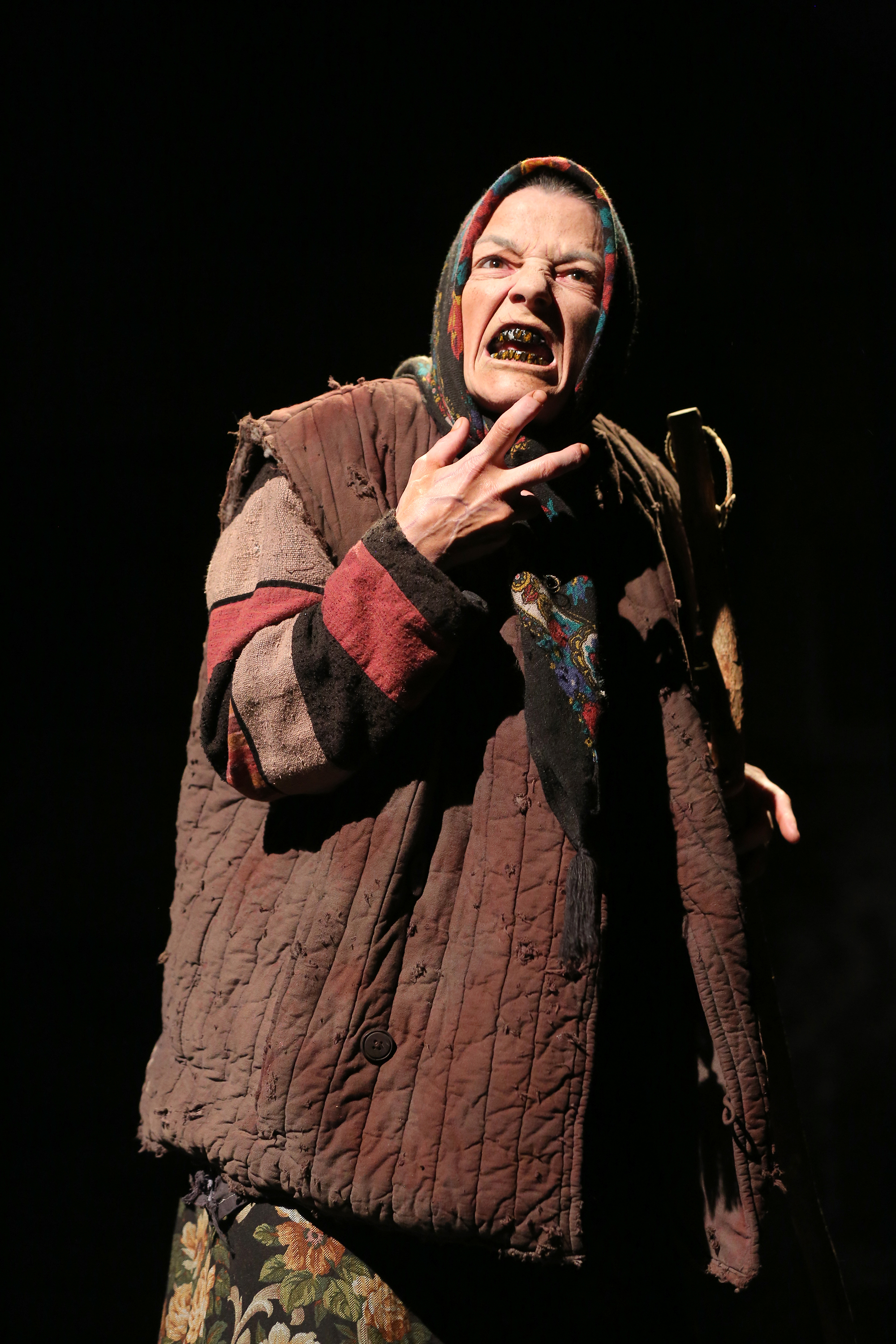

And once that note is sounded, the roles of the other two women become clearer as antagonists to Agatha’s erotic reign, which entails, in lurid Gothic fashion, a scheme of using Branwell as the means for an heir via Emilie, in a kind of incest by proxy. The other sister, Huldey (Birgit Huppuch), styles herself an author, and a famous one at that, because she keeps a journal full of her unimaginative unhappiness, and, in Agatha’s scheme of things, is decidedly de trop. The maid, Marjory (Hannah Cabell), has other designs and finds Huldey an apt enough dunce for her plans. In essence, then, there are two strong-willed characters, Agatha and Marjory, both played with subtle shadings, and two weaker characters, Huldey, a fulsome comic role, and Emilie, more or less our heroine and avatar in this uncertain situation.

Huldey (Birgit Huppuch), Marjory (Hannah Cabell)

Another nice touch is the character of Marjory. As parlor maid, she is called Mallory and is pregnant, due to the master’s inclinations we assume; as scullery maid, she is called Marjory and suffers from typhus. The blending of both in one, besides a recurring joke, is also a way of attesting to the slippery nature of roles—social, sexual, dramatic. Eventually we hear Marjory’s voice in her own journalizing only to realize that she is the most interesting of the four.

And what is our heroine’s role? In a brief exchange between the sisters early on, Huldey asks why a governess is needed when “there is nothing to govern,” an assertion that Agatha gently mocks. Is Emilie to be Agatha’s creature, surrogate mother to the heir, a confidante for lonely Huldey, as the latter hopes, or the eventual mistress of the moors?

Along the way, there is the insipidity of Huldey for amusement, the oddly touching amour between Mastiff and Moor-Hen, sudden violence, and a show-stopping murder ballad. There’s also Alexander Woodward’s wonderful set that gives us both a creepy manor house, complete with secret door, and the moody moors, and eventually a half-and-half of the two that creates a visual commentary on how much the effect of the outside is coming inside. Lighting, costumes and sound design and excellent casting all contribute to making the show’s mix of the comic and the creepy work so well.

With its quizzical tone, The Moors establishes a world of shifting possibility—nothing is as it seems, and nothing will change, but everything will be different. Slyly fascinating, The Moors is first-rate entertainment.

The Moors

By Jen Silverman

Directed by Jackson Gay

Scenic Designer: Alexander Woodward; Costume Designer: Fabian Fidel Aguilar; Lighting Designer: Andrew F. Griffin; Sound Designer and Original Music: Daniel Kluger; Fight Director: Rick Sordelet; Production Dramaturg: Maria Inês Marques; Casting Director: Tara Rubin Casting; Stage Manager: Avery Trunko

Cast: Jeff Biehl, Hannah Cabell, Birgit Huppuch, Jessica Love, Kelly McAndrew, Miriam Silverman

Yale Repertory Theatre

January 29-February 20, 2016