Review of Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein, Yale Repertory Theatre No Boundaries Series

It may be surprising to see Mary Shelley’s cautionary novel about the overweening hubris of those who would play God in a time of scientific advance altered to become a story of the importance of nurturing in a time of anxiety about the future, but that’s what Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein, at Yale’s University Theatre as part of the No Boundaries Series, offers. By linking the death of Clara, the child of Mary (Sarah Fornace) and Percy Shelley (Leah Casey), after weeks of life, with the reanimation of dead tissue undertaken by Mary’s famed hero, goggle-eyed Victor Frankenstein (Fornace), this version of the Gothic story becomes a sort of wish-fulfillment fantasy of bereavement.

That thematic interest, however, does get lost a bit in the trappings of the familiar horror-story genre that Manual Cinema, an experimental theater troupe from Chicago, also freely borrows from. “The Creature” created by Victor in his lab has become known popularly as “the Frankenstein monster” or simply Frankenstein, and that makes for an expectation of moody castles and grave-digging and callous crimes (all lovingly evoked). In Shelley’s version, the Creature does some horrible things to Victor’s family in revenge for how his “father” treated him; here, the Creature is more sinned-against than sinning and therein lies a key difference—though the fate of the family he encounters, including the requisite friendly blindman, is unclear to me, their house is torched.

Manual Cinema’s Creature, who is misshapen but childlike, is a puppet, a live actor (Kara Davidson) and a shadow puppet. That should indicate the range of what this incredibly inventive and entertainingly creative troupe manages to manifest to our wonderment. Their key technique is creating a film live, using shadow puppets, actual puppets, live actors, and a handful of musicians on the front of the stage playing the score of this silent film/theatrical event live. At one point, shadow puppets give way to actor-shadows in a subtle sleight-of-hand. Visually rich and complex, the show is a compelling hybrid of theater and film.

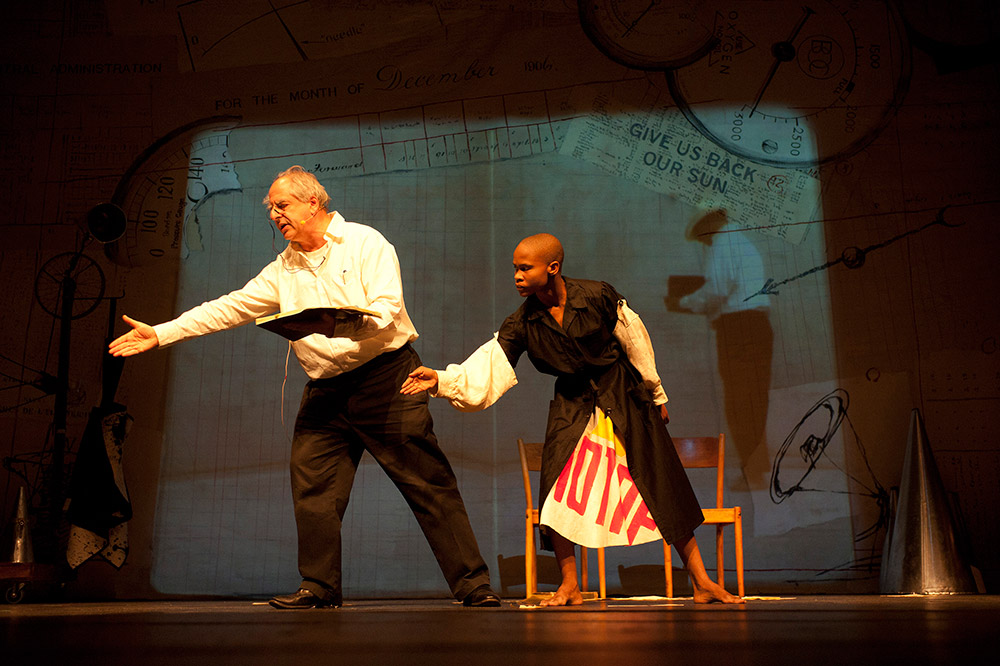

Leah Casey in Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein (photos by Elly White, Michael Brosilow at Court Theatre, Chicago, from Manual Cinema website)

The audience can concentrate on the projections (which is Rasean Davonte Johnson’s métier) while stealing glances at the group upstage who are making those visuals happen. Camera work can be astounding, with close-ups of the Creature both unsettling and full of pathos, and Furnace’s tendency to press close to the camera becomes an emotive crux much like certain stylized facial expressions in silent films. Indeed, the only language in the film comes from silent-movie placards containing Shelley’s text and the only voice heard is the lovely, ethereal vocals of Leah Casey.

The score, by Ben Kauffman and Kyle Vegter, uses percussion in a mood-creating way and all the musicians, led by Peter Ferry, make percussive sounds as well as playing flutes, clarinets, cello and piano. The texture of the sounds and the texture of the visuals make for a seamless, immersive experience and that, more than story per se, is the most fascinating aspect of the show. The sound design (by the composers) and the visual design (Johnson), including costumes and wigs by Mieka Van Der Ploeg and lighting by Claire Chrzan, with puppetry by Lizi Breit and props by Lara Musard, is remarkable throughout and almost preternatural in effect. To help satisfy your curiosity about how the 90+ minute multimedia epic you’ve just seen was done, the audience is invited up onto the stage after the show to tour the props, puppets, screens, cameras, costumes and instruments.

Peter Ferry in Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein (photos by Elly White, Michael Brosilow at Court Theatre, Chicago, from Manual Cinema website)

Does the show offer a fully satisfying realization of Shelley’s famed creation? The manner of the story is incredibly well-conveyed, with the dark atmosphere and great backgrounds apropos to the Gothic imagination. The prologue—about the birth and loss of Clara and the storied summer in 1816 vacationing on Lake Geneva when the Shelleys, along with Lord Byron and his personal physician, were each challenged to create “a ghost story,” that led to Mary writing Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus—makes for a slow start, though it’s key to the concept by Drew Dir (and the depiction of Byron and Shelley as dudes of our day grabs laughs).

The insistence, in this all female cast, on Victor mirroring Mary makes for a refreshing spin, a way for Mary to appease the ghosts of her dead mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, who died shortly after Mary’s birth, and her own dead daughter (no mention is made of William, the child born to the Shelleys in 1816). The effort by Romantic studies to possess this material has led to all sorts of conjectures about Mary’s relation to her characters. Manual Cinema’s take seems much in-keeping with the notion of Mary Shelley as the hero of her own story, and thus akin to the mad genius who gave birth to one of the most enduring, mysterious and chilling figures in English literature.

Frankenstein

Adapted from the novel by Mary Shelley

Concept by Drew Dir

Devised by Drew Dir, Sarah Fornace, and Julia Miller

Original music by Ben Kauffman and Kyle Vegter

Storyboards: Drew Dir; Music and Sound Design: Ben Kauffman and Kyle Vegter; Shadow Puppet Design: Drew Dir and Lizi Breit; Projections and Scenic Design: Rasean Davonte Johnson; Costume and Wig Design: Mieka Van Der Ploeg; Lighting Design: Claire Chrzan; 3D Creature Puppet Design: Lizi Breit; Prop Design: Lara Musard; Stage Manager, Video Mixing, and Live Sound Effects: Shelby Glasgow; Assistant Stage Manager: Kate Hardiman; Sound Engineer: Mike Usrey

Cast: Leah Casey, Maren Celest, Kara Davidson, Sarah Fornace, Myra Su

Musicians: Peter Ferry, percussion; Michael Chen, clarinets, aux percussion; Rachael Dobosz: flutes, aux percussion, piano; Lia Kohl: cello, aux percussion, vocals

Yale Repertory Theatre

No Boundaries Series

November 7-9, 2019