Review of Refuse the Hour at Yale University Theater

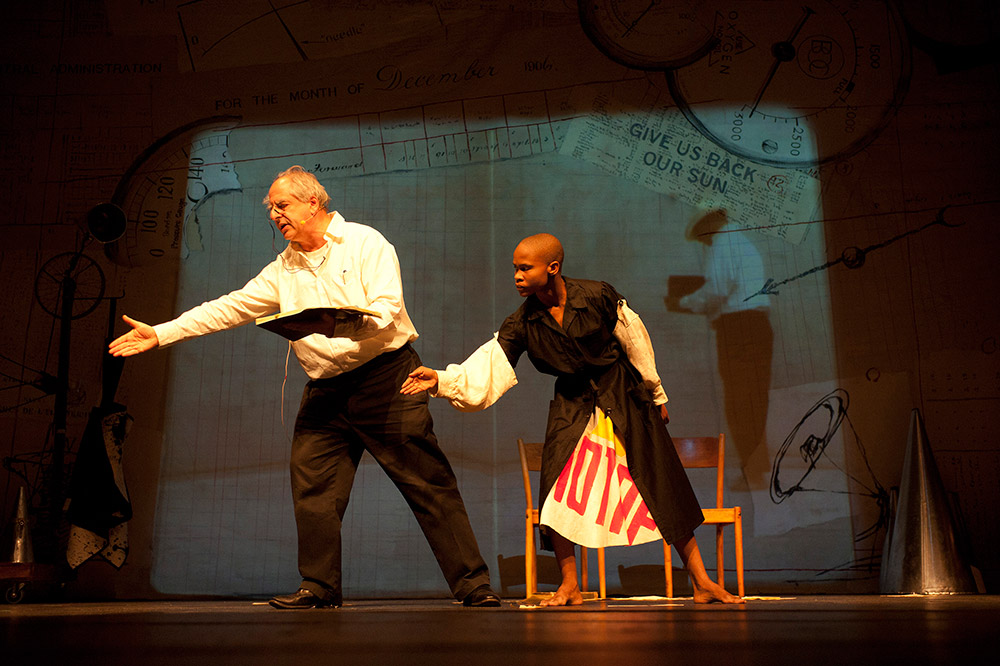

William Kentridge’s Refuse the Hour offers an overwhelming array of riches. A kind of traveling video and stage accessory to Kentridge’s five-channel video installation The Refusal of Time, the show has been brought to the Yale Repertory Theatre season as part of the No Boundaries series and staged at the University Theater for two performances only. As theater, the piece involves narration from Kentridge, onstage throughout, fascinating movement from Dada Masilo, an array of artistically achieved and fun to watch videos by Kentridge and Catherine Meyburgh, a varied score—including operatic arias, African chants and beats, and, often, singing backwards—composed by Philip Miller, and a wealth of other technical contributions, including interesting machines that seem to play music as grand wind-up toys and/or automata. So much is going on at once, at times, one really needs to see the piece more than once, or, given the show’s themes, maybe from two different vantage points at the same time.

Time is the main theme and it’s evoked through a range of fertile sketches, beginning with Kentridge, who grew up in South Africa, telling us of traveling, when he was eight, on a train with his father who read to him the story of Perseus. It’s not the famed slaying of the Gorgon, Medusa, that captures the boy’s imagination, rather it’s the way—deemed “intolerable” by the young Kentridge—that Perseus’ grandfather, Acrisius, fulfills the prophecy that he would be killed by his grandson. The confluence of Acrisius having to be, improbably, at the top of a viewing stand, in disguise, at the moment that Perseus flings a discus that will end his life becomes a symbol not only of the impossibility of fleeing one’s fate, but of the full implications of trying to determine consequences of a decision. Kentridge sums it up with the powerful line, “once thrown, the discus cannot be called back.”

from Refuse the Hour

One could say that the series of segments that comprise Refuse the Hour are forms of meditation on how we try to measure time and the effects we are having in time. At one point, giant metronomes are set in motion, at different rates. At another point, we see a video of Kentridge walking about his studio in an endless loop while animated objects and design elements interact at intervals with the main image. We see a video of a kind of African homecoming scene from which frames have been removed to create odd jumps and rhythmic effects. We see fluid dance movements from Masilo that make manifest the power and grace of the human body as matter alive in time.

Dada Masilo

To call the background of videos “background” is a misnomer as they provide much of the visual interest, though there are striking choreographed effects taking place onstage as well, sometimes with the video and live action interacting as though they shared time and place, which in a sense, but only in a sense, they do. And Kentridge’s animation process is itself a major artistic achievement, using both subtle technical effects and erasures and re-drawings that lend a wonderfully spontaneous handmade feel to the images. Indeed, the notion that works that are rehearsed and staged, arranged and taped, can be “spontaneous” plays into the show’s best conceits, which are about the effect of time and timing.

Kentridge and his dramatug Peter Galison have chosen to dramatize an array of temporal concepts—having to do with entropy, black holes, and the introduction of European clock-time into African colonies where the sun and not the clock had been the traditional arbiter of time. Throughout the show what we are seeing and hearing requires the utmost control of timing—particularly some wonderful effects of synchronous movement (involving numerous moving parts and sound-making people and instruments), and a vocal interplay between Joanna Dudley and Ann Masina, the one onstage, the other in the balcony, that is impressive not only for its artistry but also as an exemplary instance of music as the language of time.

As the show goes on, some elements and lines recur (such as variations on T.S. Eliot's line, “That is not what I meant at all”), and all seems to be in a flux that makes for almost trance-like viewing. Perhaps, in the end, the overall effect is of stretching time or inhabiting it in different ways, so that, at times, we feel part of a very busy but arrested movement, non-moving parts in a clockwork display. One of the ideas that Kentridge expounds at length—that every act we perform is “broadcast into space”—makes us aware that our time as audience is time spent at the mercy of the magicians on stage. It’s an hour and a half one should not refuse to grant.

William Kentridge, Dada Masilo

Refuse the Hour

Conception and Libretto by William Kentridge

Music composed by Philip Miller

Choreography: Dada Masilo; Dramaturgy: Peter Galison; Video Design: Catherine Meyburgh, William Kentridge; Scenic Design: Sabine Theunissen; Movement: Luc de Wit; Costume Design: Greta Goiris; Machine Design: Jonas Lundquist, Louis Olivier, Christoff Wolmarans; Lighting Design: Felice Ross; Sound Design: Gavan Eckhart; Video Orchestration: Kim Gunning; Music Direction: Adam Howard; Music Arrangements and Orchestrations: Philip Miller, Adam Howard

Performers: William Kentridge; Dancer: Dada Masilo; Vocalists: Joanna Dudley, Ann Masina; Actor Thato Motlhaolwa; Trumpet and Flugel Horn: Adam Howard; Percussion: Tlale Makhene; Violin: Waldo Alexander; Trombone: Dan Selsick; Piano: Vincenzo Pasquariello; Tuba: Thobeka Thukane

Yale Repertory Theatre

November 6-7, 2015