Review of Broken Glass at Westport Country Playhouse

To celebrate the centennial of the birth of famed playwright Arthur Miller, Westport Country Playhouse has staged a late Miller play. Broken Glass, which was nominated for a Tony for 1994, debuted at the Long Wharf Theatre. The revival at Westport, directed by Artistic Director Mark Lamos, does the play proud, with some of the finest acting to have graced Connecticut stages this year. The entire cast is excellent and match their roles perfectly, while two actors familiar to Connecticut audiences—Steven Skybell and Felicity Jones—do some of their best work to date.

The play, like most of Miller’s best-known plays, is very intense and doesn’t offer much in the way of lighter moments. Set in the U.S. in 1938, the period of the play is historically significant as the time of “Kristallnacht,” or the night of broken glass, as Nazis came to power in Germany and took Austria, destroying Jewish shops, burning synagogues, beating-up Jews, and perpetrating other acts of thuggishness in their fascistic zeal. At this time, a Jewish couple in America, Phillip and Sylvia Gellberg, played by Skybell and Jones, are experiencing a mysterious kind of trauma. Sylvia suddenly finds herself unable to walk. As the play opens, Phillip is receiving word from cautious and thoughtful Dr. Hyman (Stephen Schnetzer) that the doctors can find nothing physically wrong with Sylvia. He believes the problem is psychosomatic, and that means delving below the surface in the Gellbergs’ marriage.

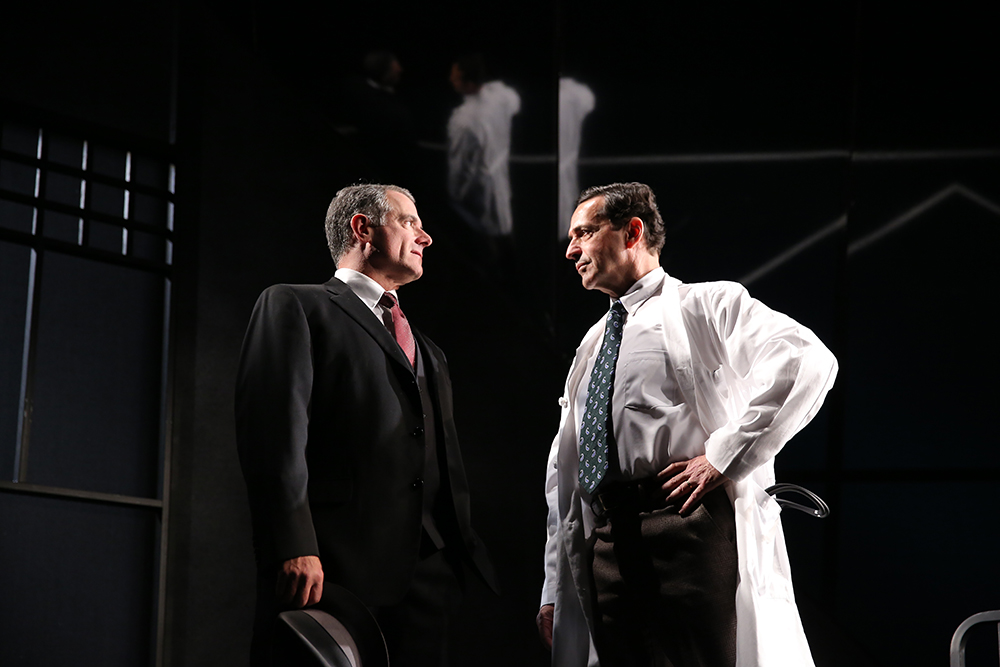

Steven Skybell (Phillip Gellburg), Stephen Schnetzer (Dr. Harry Hyman)

In that first scene, Skybell lets us learn much about Phillip: his reticence, his deep concern for his wife, his difficulties with her and with the marriage that has shaped him, his pride in his role as the only Jew employed by a Brooklyn trust company (he works in foreclosures) and in his son as a Jew rising in the armed forces, and his deep ambivalence toward other Jews and to “what is happening in Germany.” He’s mainly concerned that outright antisemitism there may inspire more aggressive forms of antisemitism here. Phillip is not really a sympathetic character and yet Skybell makes us care about him even though there’s a real threat here. He may crack up, he may become violent. Before the evening ends, we will see him weep, plead, suffer, accuse and attack, and drop to the floor with a heart attack. And through it all Skybell makes us consider what happens to a man when he is out of his depth, when the delicate détente of his marriage begins to fray in such a way that professional help becomes imperative.

It’s hard to believe the play was written in the Nineties, so steadfastly does it feel like a vision from an earlier time: the Thirties as seen by the Fifties, perhaps. Which is a way of saying that the writing feels like it must precede the Sixties and the Seventies with their greater laxity of locution. Dialogue in this play may feel prosy, on the page, but as delivered by this stellar cast, directed by Lamos, who has worked directly with Miller in the latter’s long career, the dialogue’s precision and nuance of character is exemplary. Even relatively minor roles, such as Phillip’s ultra-WASPy boss Stanton Case (John Hillner) and Harriet (Merrritt Janson), Sylvia’s sister, come across as actual people with actual lives.

Harriet, in particular, speaks with authority about her sister’s life in a way that seems informed by decades of observation and gossip. And Dr. Hyman’s wife, Margaret (Angela Reed), provides useful shading to the good doctor; her sense of how easily he becomes infatuated with his female patients makes us wary of his interest in the psychology of Sylvia’s case. Miller lets his minor characters play their parts and get out of the way; their contributions help us grasp the levels of the situation and add a deeper sense of the play’s “no man is an island” context. The Skybells, the Hymans, are in many ways unremarkable, and yet, once we begin to remark them, we will see subterfuge and shame and other issues, some long-buried, some still close to the surface, that must be confronted.

Stephen Schnetzer (Dr. Harry Hyman), Felicity Jones (Sylvia Gellburg)

The use of paralysis and impotence as figures for U.S. Jewry’s inability to do anything for their German counterparts is a bit too obvious as metaphor, we might say. But to treat ironically Miller’s figures for an international incapacity to help the persecuted (quite relevant to the moment with the question of Syrian refugees) would be to spoil the play horribly. Sylvia Gellburg’s reaction to such suffering is physical, and, in her marriage long ago, the failure of the physical, bodily aspect of love became the occasion for violence. Miller’s text seems true to the Thirties where Freud’s “Jewish cure” of talking about the past to find psychological truth comes up against the “Jewish question”—both are aspects of life not often talked about in polite society then. And so the drama of sadly unhappy people coming to grips with both resonates as catharsis-seeking theater.

Felicity Jones (Sylvia Gellburg)

Much of that level of feeling comes from Felicity Jones’ subtle enactment of Sylvia Gellburg. There are so many ways one might react to her predicament: aging woman’s last hope of attracting sensitive male attention; unhappy wife finding a way to pay back her husband, who doesn’t dominate so much as demand acceptance, for his treatment of her; sensitive woman driven to distraction and illness by the methodical brutality of the times; confused and lonely soul needing compassion, and finding, in Kristallnacht, a figure for mankind’s lack of compassion. Jones makes us see all this in Sylvia’s strength and weakness, her passion and her pathos. Even her tears come to us through a veil of attribution: is it self-pity, a play for sympathy, or a dawning grasp of a tragic sense of life? Key to Miller’s play is the notion that, if people can only find a way to speak of what ails them, much that is dark and disturbing to ourselves about ourselves might become less grievous and appalling. We might have to accept how much we need the views of others to see ourselves aright.

Michael Yeargan’s scenic design—including artfully manipulated bed and chairs and a reflective backdrop that, before the play begins, shows the audience to itself and later lets us see bedridden Sylvia from above—and the lighting by the impeccable Stephen Strawbridge, together with Candice Donelly’s costumes and David Budries’ sound design, add to the impressiveness of this fully realized production of a challenging and rewarding play.

Arthur Miller’s

Broken Glass

Directed by Mark Lamos

Scenic Design: Michael Yeargan; Costume Design: Candice Donnelly; Lighting Design: Stephen Strawbridge; Sound Design: David Budries; Props Master: Karin White; Movement Consultant: Michael Rossmy; Dialect Coach: Louis Colaianni; Casting: Tara Rubin Casting; Production Stage Manager: Matthew Melchiorre; Photographs: T. Charles Erikson

Cast: John Hillner; Merritt Janson; Felicity Jones; Angela Reed; Stephen Schnetzer; Steven Skybell

Westport Country Playhouse

October 6-24, 2015