Since the start of the current semester, the Yale Cabaret has been on a roll. Each week has given audiences another provocative offering. This weekend the play is Yaël Farber’s He Left Quietly, which dramatizes the ordeal of Duma Kumalo, an inmate condemned to death row in apartheid South Africa for an act of mob violence in which he did not participate. Rather, he was arrested and condemned for political rather than criminal reasons. Kumalo served three years, awaiting death and enduring the dehumanizing and humiliating treatment of his captors, only to be reprieved, due to public pressure, from hanging (he had already been measured for the noose and his coffin) less than 24 hours before his time. After another four years he was released, only to experience the stigma of being a former prisoner who was never cleared of the crime. As originally staged, from 2002 until Kumalo’s death in 2006, He Left Quietly featured Kumalo himself. The play was produced as a docu-drama, with Kumalo telling his own scripted story while a professional actor would play “Young Duma,” acting out, mostly in mime, the events Kumalo describes, and a female actor would play “Woman”—a part that at times represents Farber herself, at other times the agents of the government, or a narrative voice. As staged at the Cabaret, directed by Leora Morris, all three parts are played by second-year actors at YSD.

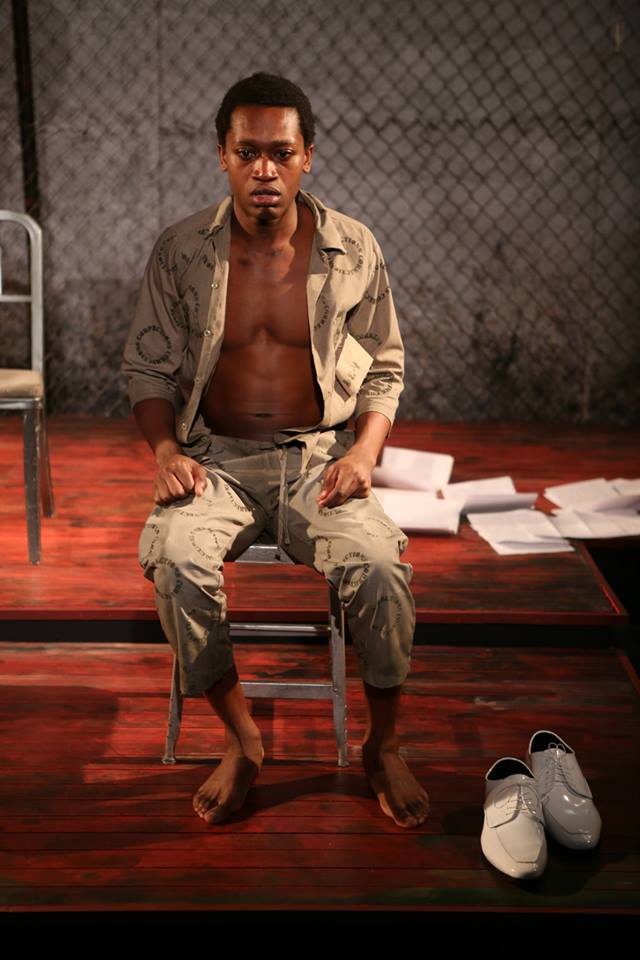

Playing Duma, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II creates a sense of a man who has come through a harrowing ordeal both wiser and humbler. He begins by asking “how many times can a man die” and when the actual moment of death occurs. The main thrust of the show is not, as we might assume, indignity and political outrage, but rather the kind of insight that comes from having faced death and lived. In presenting his experiences as theater, Duma seems to have gained a philosophical detachment that makes him a benign narrative presence recounting what comes to seem a ritual cleansing: stripping away the accoutrements of the everyday—a scene in which Young Duma buys a pair of stylish shoes that, unknown to him at the time, he would wear only once: to be sentenced to death, establishes an “all is vanity” tone that Duma chuckles about; then the humiliations—such as a prison uniform deliberately too small—and the existential reminders, as current inmates wear the uniforms and sleep in the bedclothes, unlaundered, of those already killed; finally, the surrendering even of one’s attachment to life, as Duma says his goodbyes to his father and other loved ones and accepts the unique date with death we all inevitably face. The reprieve comes as almost a taunt, a way of showing that he is indeed a puppet on the strings of the State. Abdul-Mateen maintains such a dignified and knowing air that we see not a man consumed by suffering but rather one ennobled by it.

On a plain wooden stage set with a couple chairs, a primitive toilet, and a pile of shoes, backed with a chain-link face, He Left Quietly makes the most of its ritualistic overtones, even as it gives full drama to Duma’s individual plight. Enacting the range of emotions Duma endures—such as rage at his former lover, wracking sobs at his own fate, and, very movingly, teary solidarity in song for Lucky, a comrade gone to the gallows—Ato Blankson-Wood continues to impress viewers. The final tableau of Blankson-Wood silhouetted against the wall/fence, looking off, acts as a comment on the entire story of Kumalo, as a man who, once imprisoned unjustly then returned to the world of apartheid, must endure years under the shadow of the system that condemned him, while eventually taking control of his story as a tale to be told, and enacted again and again, for audiences. Without Kumalo’s own presence in the play, the play becomes more theater than document, so that we may find in it, as with any play, meanings that go beyond the actual events of Kumalo’s life.

From that point of view, the weakest aspect of the play is the role of Woman. Maura Hooper does a bravura job of playing sympathetic witness, indifferent judge, and other roles, but the part as written comes to seem a bit too contrived, a theatrical touch rather than a direct reflection of Kumalo’s experience—which is never true of Duma’s descriptions or Young Duma’s enactments.

Stark, unsettling, but ultimately redemptive, He Left Quietly makes its audience bear witness to the many unsung songs of political prisoners and unjust executions in our world. It is to Farber and Kumalo’s credit that they can convey both the extraordinary circumstances of Kumalo’s story as well as the more general existential condition we all face, and, most tellingly, the very real threat of political reprisals by the state’s arbitrary violence—never more fearsome and pitiless than when sanctioned by the law of the land.

He Left Quietly By Yaël Farber Directed by Leora Morris

Dramaturg: David Clauson; Set: Christopher Thompson; Lights: Andrew Griffin; Sound: Kate Marvin; Costumes: Fabian Aguilar; Projections: Reid Thompson; Technical Director: Mitchell Cramond, Mitch Massaro; Stage Manager: Sonja Thorson; Producer: Libby Peterson

Yale Cabaret February 27-March 1, 2014