Review of Other People’s Money, Long Wharf Theatre

The sign of a good play is that viewers can read different things into it at different times, and directors can find new relevance in it. Jerry Sterner’s Other People’s Money, at Long Wharf, directed with sharp transitions by Marc Bruni, could easily seem a trip back to the late 1980s when business liquidators were an up-and-coming breed, “mergers and acquisition” became practically a household phrase, and old production standbys like automobile manufacture became ailing dinosaurs of the corporate world. While the period aspect of the play is still very much prevalent, it’s hard to watch the play in 2016 and not think of the recent election. Allegory may be in the eye of the beholder, but I think not.

We’ve got Wire and Cable, an all-American company that cares about its employees and their families, owned by Mr. Jorgenson (Edward James Hyland), a conscientious and somewhat loquacious elder who admires Harry Truman and treats the business like family. He’s got a very loyal assistant, Bea (Karen Ziemba), who sees no divide between work and her personal life. Both are dedicated to “the American Dream” as a solvent business that makes a good product and provides decent lives for all involved, debt-free. They don’t even have any outstanding fines with Environmental Protection. The manager, Coles (Steve Routman), is a canny heir apparent, serving his time until the old man steps down and he can take over and modernize a bit.

Garfinkle (Jordan Lage), Kate (Liv Rooth) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Into their cozy little world comes crass, big league player Garfinkle (Jordan Lage), a self-satisfied man of business who exists to make money, legally. He’s rapacious, avaricious, and even charming in a cold-blooded way. He’s buying up shares not because he wants Wire and Cable to make him money as a satisfied stockholder, but because he wants to gut the still breathing carcass and make his money off its dismemberment. The only person who might figure out a way to stop him is a blonde female lawyer, Kate (Liv Rooth), Bea’s daughter, who dresses sharply and is tough-as-nails, and who is more than equal to any “grab ‘em by the pussy” innuendo that might come her way. In an amusing sequence, she gets Garfinkle to grab his own crotch and give it a stern talking to.

What’s at stake? Well, if you’ve been wondering what it means to put the fox in the henhouse, by democratic consent, then this play might be the kind of entertainment to light your day. It shows us how vulnerable are core values—like loyalty and dedication—in the face of the almighty buck and the historical inevitability. A world where naked self-interest makes the wheels go round, and the devil take the hindmost. And, though Wire and Cable is in Rhode Island, we’re watching the predatory tactics that helped destroy jobs in the dissatisfied Rust Belt.

In Bruni’s taut direction, the play is even better than the script, and that’s because his crackerjack cast has a sense of the pace of TV drama, say, The Good Wife. There are still speeches that fall a little short of crisp, and the second act has too many scenes and way too much speechifying, but this cast does all it can to sell it. And the set by Lee Savage makes it all feel real.

Bea (Karen Ziemba), Jorgenson (Edward James Hyland), Garfinkle (Jordan Lage) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

As Garfinkle, Lage is no doubt way better-looking than Sterner envisioned—the script seems to call for a bit of a donut-popping schlub, maybe even with a bad toupe—but he plays the part with a kind of greased ease that recalls, at times, Pacino as Roy Cohn. Garfinkle is never quite that foul, but he tries. And he gets to comment, in a winning, “get a load of this” way, on the other team’s efforts to undermine his intentions (it’s almost like he’s hacking their strategy). Lage plays large, but there are lots of nice touches, as when he first takes in and sums up in a glance the proud but unpretty site and Jorgenson’s sentimental grasp of business.

Hyland is quite good as Jorgenson, giving the head man a very lived-in feel. He seems sort of doddering but can lead when his back’s to the wall. It’s clear that Sterner wants us to feel something more is at stake than a “seen better days” business, and Hyland makes us feel the heat of the man who watches what little legacy he had go under.

Kate (Liv Rooth) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Best of all may be Rooth, who acts the hell out of Kate. It’s a role that requires considerable presence of mind as Kate plays the pressured go-between, trying to outsmart Garfinkle, while shamelessly flirting with him, and trying to get Jorgenson to fight for his life with strategy, even if it means going low when the other side goes low.

The scene where Kate gives the other three the what’s-what on how to survive—with “shark repellent” and “poison”—is a masterful riff on how the system can be worked to advantage. Typically, the good guys think of themselves as too good to think of even playing at bad. And then there’s the possibility that, good or not, some will sink the ship to save themselves.

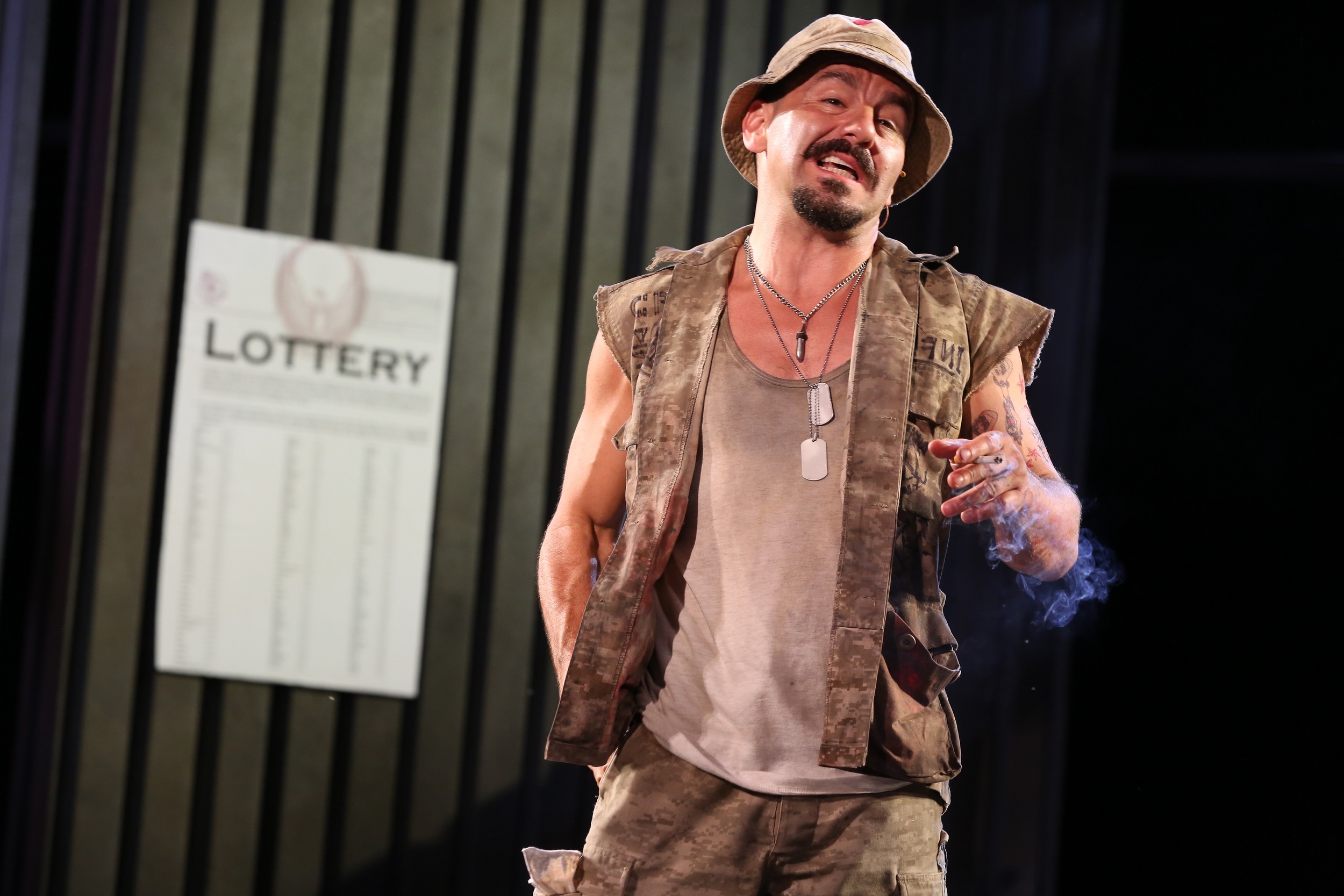

Garfinkle (Jordan Lage), Coles (Steve Routman) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Coles gets the first and last word, and Routman plays it with the clear sense of a man who never takes his eye off the balance sheet, managing to humanize the pro who supports a thing not because it’s right or better than another thing, but because he’s paid to. Ziemba’s Bea is the other side of the coin; she supports Jorgenson, not because he’s right, nor because she’s paid to, but because she loves him, giving a venerable veneer to the office romance.

Sterner draws the lines of attack and retaliate very carefully for all the characters and it’s a treat to see them treated to such well-crafted performances. Sure, it’s fun to spend other people’s money, and it’s also fun to spend time with Other People’s Money.

So, what d’ya think of that payoff?

Bea (Karen Ziemba), Jorgenson (Edward James Hyland) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Other People’s Money

By Jerry Sterner

Directed by Marc Bruni

Set Design: Lee Savage; Costume Design: Anita Yavich; Lighting Design: David Lander; Sound Design: Brian Ronan; Production Stage Manager: Peter Wolf; Assistant Stage Manager: Amy Patricia Stern; Casting by Calleri Casting; Assistant Director/Drama League Directing Fellow: Jesca Prudencio

Cast: Edward James Hyland; Jordan Lage; Liv Rooth; Steve Routman; Karen Ziemba

Long Wharf Theatre

November 23-December 18, 2016