Ryan Campbell, a second-year playwright in YSD, is a ballsy writer. A New Saint for a New World, now playing at the Yale Cabaret, begins with the premise of Joan of Arc returned to earth in 2010 to “have fun and hang out,” to make up for the bad shit that happened to her the first time, back in the 15th century, and it ends with a vision of God, in a cameo by the Big Man himself, confessing he’s a bit at loose ends. Campbell’s play, directed by second-year director Sara Holdren, is equal parts audacious comedy and earnest searching. The opening scene between Joan and her boyfriend, Bott (Aaron Bartz, suitably bemused), smacks of those sit-coms where “the wife” has to explain something, such as “I’m really a witch” (Bewitched) or a spy, or what-have-you. Here, the revelation that she’s really that Joan of Arc inspires comic understatement and characterizations of the French aristocracy and Churchmen that would feel natural in The Sopranos. As Joan, Maura Hooper has an appealing way of beseeching her boyfriend’s suspension of disbelief, in the character of her alias, while at the same time becoming more and more emphatically Joan. It’s a great tour de force of the off-hand casualness of today’s speech meeting the inspired dicta of the Age of Faith.

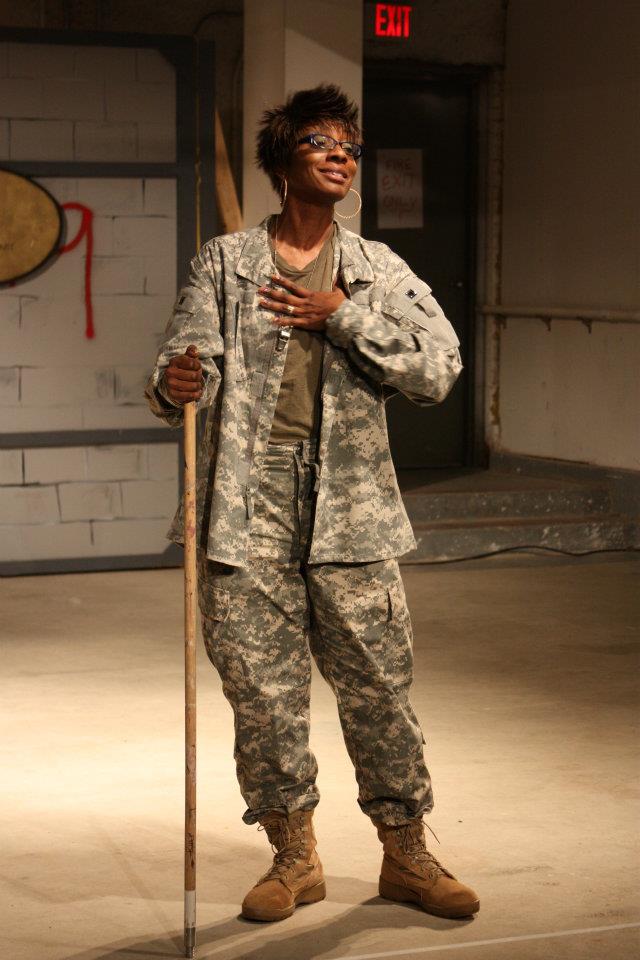

In some ways, the play never quite recovers from that outrageous opening gambit, but each of its scenes—black-out vignettes more than a continuous play, we might say—has something to offer that extends the story beyond that initial comic exploration. Joan, who got returned to earth on the condition that she not stir up any trouble, can’t help herself. Eventually she’s started another Civil War in these formerly United States. The actual terms of the battle go by a bit quickly, but the gist is that Joan, facing interrogation, has fought for the people against the kinds of power mongers who think they “represent God.” She’s being held in Arizona, so draw your own conclusions. Ariana Venturi does a great job as a chilling captor: it’s like facing capital charges at the hands of your Sunday School teacher. A steelier sense of self-righteousness, matched with meek “doing my duty” candor, would be hard to imagine.

That scene does go on a for a bit, but then there’s another explosion of comedy: Christopher Geary as a pissed-off Archangel forced to visit Joan in her holding cell, accompanied by his graphic-novel-reading sidekick (James Cusati-Moyer). Geary manages to spout exposition with the mounting ire of one who finds the situations he’s describing increasingly maddening, including the info that God has decided to go with a new start-up universe he’s just devised. Seems Earth won’t be his favorite toy for much longer.

Which leads to that new world, Kia, where Joan gets to pass some time in anything but bliss. Though we meet—in a very Dr. Who-ish vision and visitation—Okun (Annie Hägg and Elizabeth Mak), one of the oddly serene double-beings that inhabit this world, and who tries to placate Joan with offers of the goods on demand, once a warrior always a warrior, and our Joan is restless to be up to something more than “hanging out and having fun.”

Finally, looking like a coke-dusted film producer or some other Player, Jeremy Funke, in a special guest appearance, shows up to beseech Joan to play his game, offering intensity, sincerity, and a cosmic sense of detachment. It’s definitely a grand payoff.

Well-cast, well-played, with a versatile set (Jean Kim, Izmir Ickbal) that looks like bargain-basement Star Trek and costumes (Fabian Aguilar) of tacky splendor, New Saint is fun to look at as it jabs at our modern lack of belief and hope, giving us a gutsy heroine aching to achieve something in a universe that may be rather less hieratic than it was in the Middle Ages. And, like other after-worldly comedies we could mention, New Saint gets its laughs from the incongruity between our suppositions about the Grand Scheme and the way it actually tends to play out. More of that “we get the afterlife we deserve”—which now includes “after-earth” and other universes—which has been somewhere at the heart of the whole problem of how to live righteously, in principio.

An amusing, irreverent, and relevant little gem for the Easter season.

A New Saint for a New World By Ryan Campbell Directed by Sara Holdren

Dramaturg: Helen Jaksch; Set: Jean Kim, Izmir Ickbal; Lights: Oliver Wason, Caitlin Smith Rapoport; Sound: Sinan Zafar; Costumes: Fabian Aguilar; Projections: Joe Moro; Technical Director: Alix Reynolds; Stage Manager: Sally Shen; Producer: Sally Shen

Yale Cabaret April 17-19, 2014