Review of Middletown, New Haven Theater Company

Will Eno opens Middletown with a speech of welcome delivered by a “Public Speaker.” As played by Megan Chenot, the speaker presents an earnest hope that we will all feel we belong, but her litany of who “we” might be, as audience members or townies, in seeking to be all-inclusive, begins to feel vaguely unreal, a kind of labelling without a sense of precise meanings. Eventually, it starts to sound like double-talk. And that’s how language works in Middletown: it’s ho-hum average, and yet. There’s something a little unsettling about how easily what gets said doesn’t quite equate with what’s intended.

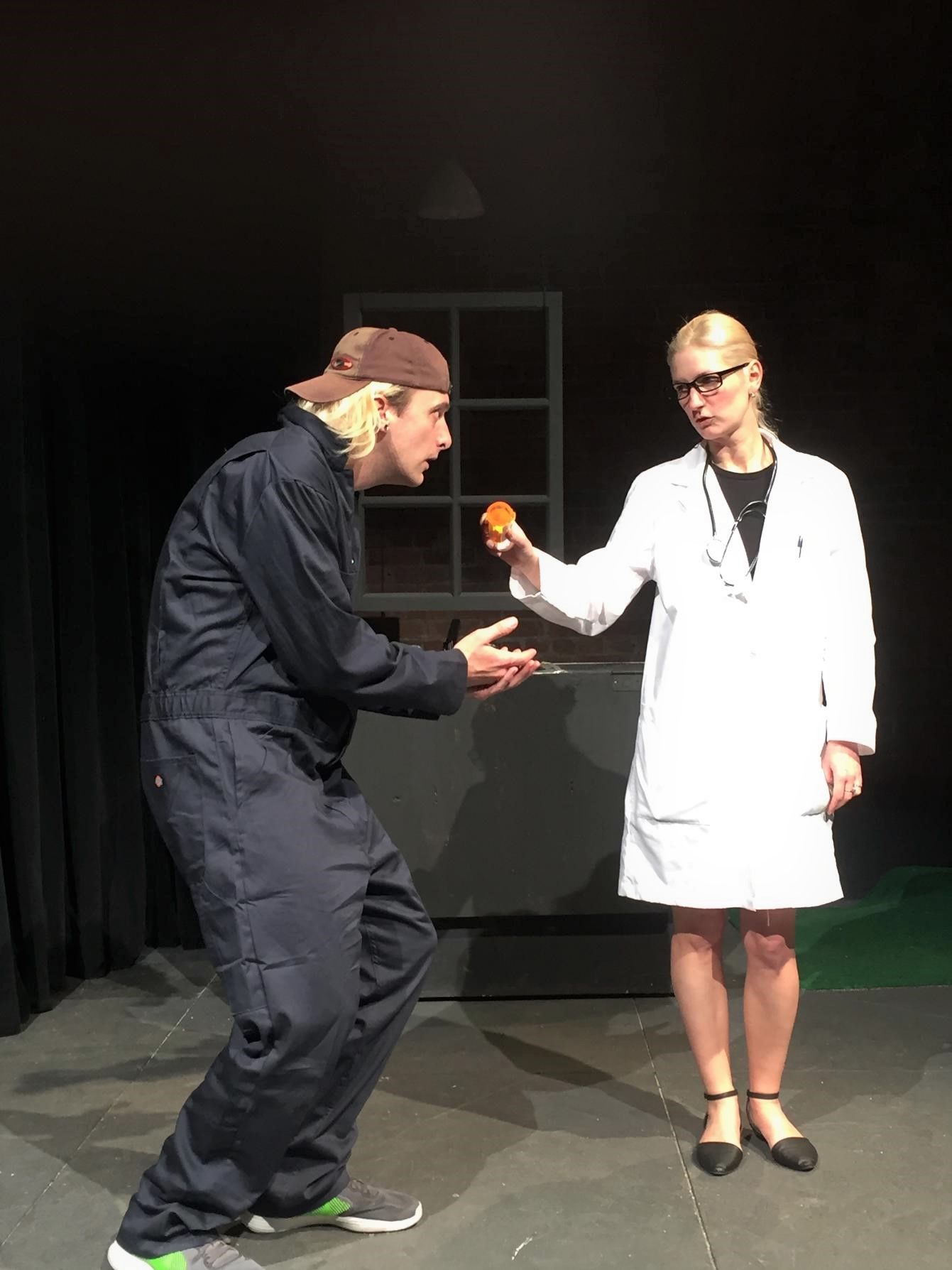

Mechanic (Trevor Williams), Doctor (Megan Chenot)

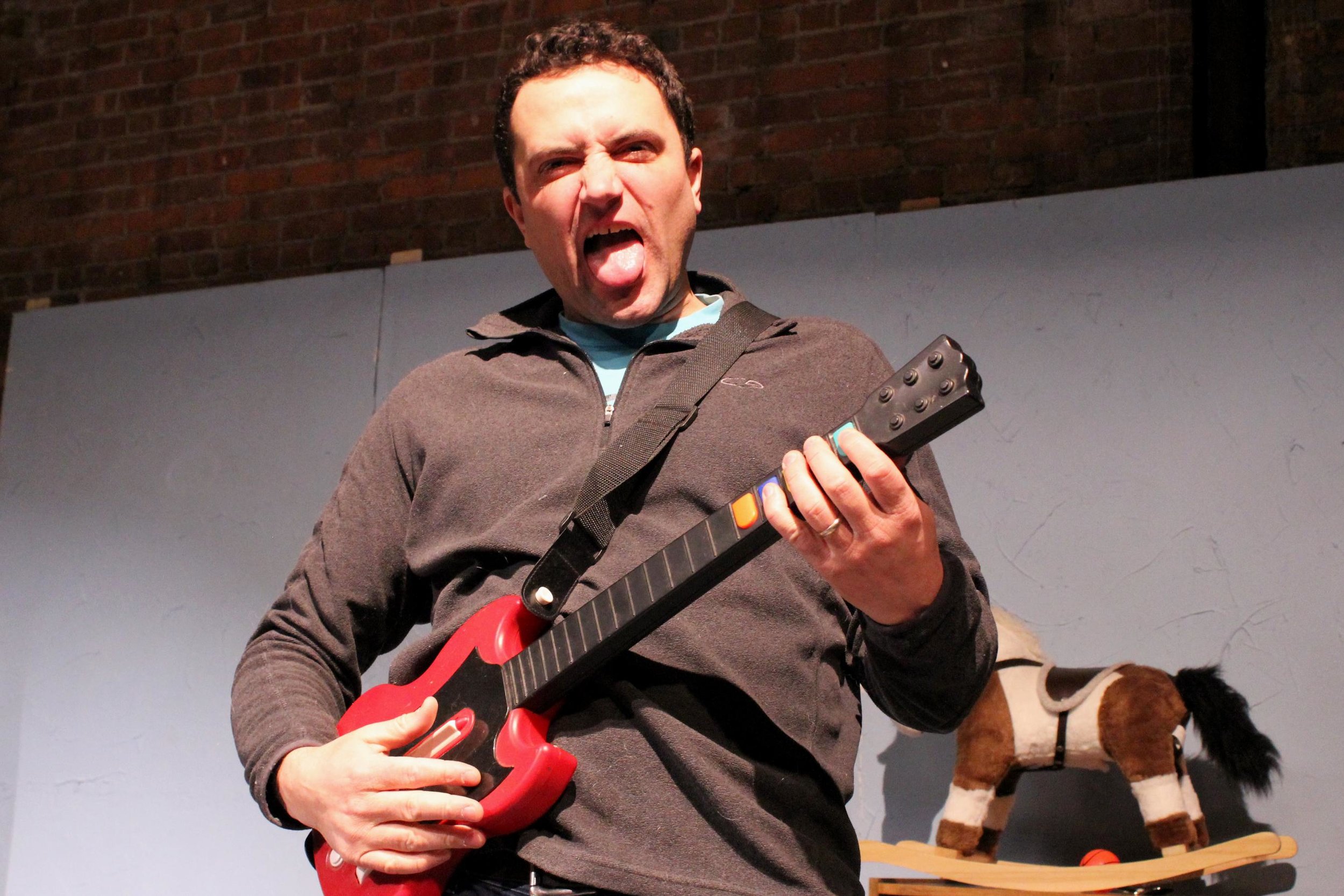

Everyone here is a job or role rather than a character. Everyone, that is, except Mary Swanson (Chrissy Gardner), a pregnant woman new to the town, whose absentee husband seems never to arrive, and John Dodge (Steve Scarpa), a local jack-of-all-trades, who reads up on gravity—“the silent killer”—and fixes things, and contemplates ending it all; whether from boredom or frustration or some more insidious malaise is hard to say. Together, these two almost put the town on the map, as it were, seeming to create a possible connection outside of assigned roles.

A key visual device is John and Mary each behind a separate window in separate houses, spied upon by the Cop (George Kulp) on his beat as if making sure they never inhabit the same place. They do, briefly, when John comes to fix the sink and their exchange is the stuff of a suburban Woody Allen where mixed signals are missed signals, and vice versa. It’s one of Scarpa’s best performances, and the promise of romance keeps us hoping, as it may for these two lonely people who would never admit their attraction.

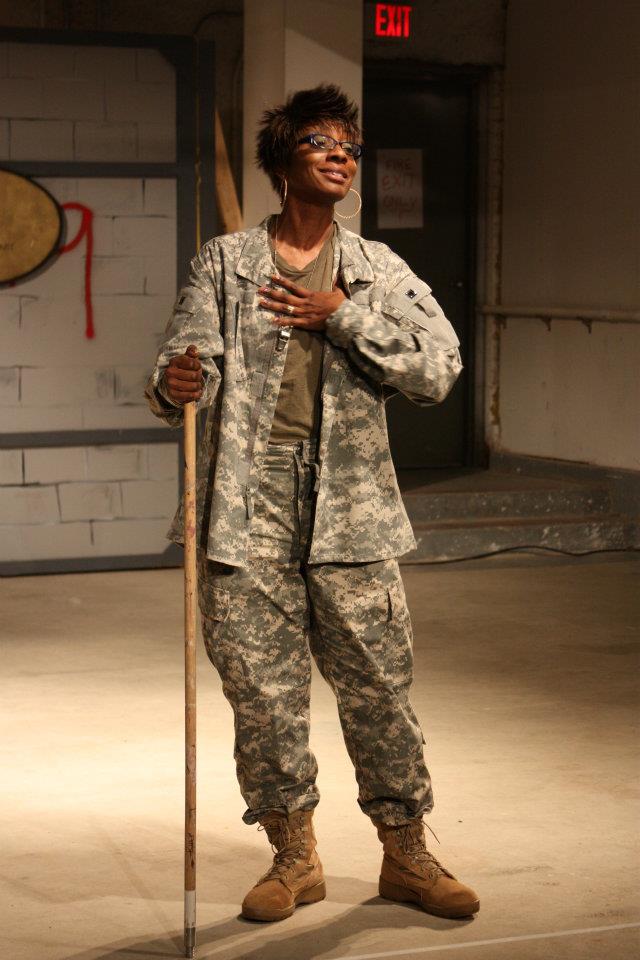

Other characters align in ways that suggest parallel purposes. A librarian (Margaret Mann) is also a kind of welcomer, as is a tour guide (Alynne Miller), characters who have a sense of belonging and an elusive sense of what makes the place itself. A tourist couple (Chaz Carmon and Erich Greene) are played for laughs as the kind of people who are content so long as there’s something to take a picture of, but they're also a version of the unhappy couple, John and Mary. More problematic is Mechanic (Trevor Williams), a ne’er-do-well who loiters on park benches—to the Cop’s irritation—and sulks in the library where his non sequitur are amusing asides, and vice versa. He’s also, sort of, our bridge to the one “famous” person from Middletown, Greg “Something,” who, as an astronaut in space, muses about his hometown and the time he had to tell some kid—the Mechanic, as a child—that his coveted rock was not a meteorite. The dashed hopes of Mechanic are, as it were, the thorn in the side of this complacent town, an indication that beneath the tepid bonhomie there might lurk harsher realities. Or at least nagging disappointment.

Just before the break, we get shown a row of folks watching the play, musing about what things mean and where they may be heading, while also making small talk. A child, Sweetheart (Alynne Miller), repeats words she’s heard, verbatim, which suggests that little insight will be gained by, as more than one character puts it, “moving your mouth and making different sounds.”

In the second half, Middletown becomes less fanciful and the effects of the encounters seem more scattershot. The parallel between John and Mary continues, in a different register, and trees and rocks still remind us that nature is more than us; the Mechanic can be surprisingly soulful, while birth and death are shown to be just stuff that happens. The general tone becomes more quizzical than whimsical, but still holds back from big emotions.

Throughout, director Peter Chenot lets the laughs fall where they may, and the cast does great with the show’s off-beat humor. There are fewer laughs in the second half, and my sense is that Middletown’s first act runs like a dream, but the second act requires more effort. Punching one event or another might help overcome the show’s even, musing tone.

The best thing here is the way the regulars of New Haven Theater Company fit so easily into their roles in Middletown. Maybe too easily.

Middletown

Written by Will Eno

Directed by Peter Chenot

Cast: Chaz Carmon, Megan Chenot, Chrissy Gardner, Erich Greene, George Kulp, Margaret Mann, Alynne Miller, Steven Scarpa, J. Kevin Smith, John Watson, Trevor Williams

Sound Design and Original Score: Megan Chenot; Choreography: Jenny Schuck; Props Master: Trevor Williams; Light Board Operator: David Stagg

New Haven Theater Company

April 27-29; May 4-6, 2017