Review of Ragtime, The Musical, Music Theater of Connecticut

Terrence McNally packs much history and drama into the Book for Ragtime, The Musical, adapted from E. L. Doctorow’s 1975 novel. And in its current production, director Kevin Connors dauntlessly packs a cast of fifteen and two pianists onto the small stage at MTC Mainstage in Norwalk to deliver a show that proves that even epic musicals can be scaled down and work well. And that’s largely due to Jessie Lizotte’s multilayered set.

The MTC show’s vitality is powerful and the diverse cast—depicting interlocking stories of New Rochelle WASPs, Harlem-based African Americans, and recent Jewish immigrants—puts across a range of songs, from the jaunty to the heart-wrenching, with great brio. As musical drama, Ragtime, which debuted in the late 1990s, is better in its parts than as a whole, as the story’s melodrama sits oddly within its sprawling treatment of early twentieth-century hot topics, and its politics, while generally progressive, feel tainted by a quaint neoliberalism.

Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (Ezekiel Andrew), Booker T. Washington (Brian Demar Jones), Sarah’s Friend (Kanova Latrice Johnson) in MTC Mainstage’s Ragtime (photos by Joe Landry) (rear: David Wolfson, conductor/music director, and Mark Ceppetelli, second piano)

Ragtime, the African American musical form that exploded into popularity in the early decades of the twentieth century, becomes both a style and theme: the music in the air compels new feelings, new relations, new possibilities. For the three main groups of characters, the new century has much to offer—not least the new Model T Ford and motion pictures—and ragtime, with its strong syncopation and innovative flair, is the soundtrack to the era, as detailed by the company in “New Music.”

Sarah (Soara-Joye Ross), Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (Ezekiel Andrew), center, and the cast of Ragtime

With Music by Stephen Flaherty and Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens, the musical is at its best when giving us glimpses of colorful material that, while entertaining, is largely for purposes of historical exposition. The entire score is ably rendered on twin pianos by conductor/music director David Wolfson and second pianist Mark Cepperelli, featuring grand set-pieces such as “Crime of the Century,” about the early tabloid sensation/showgirl Evelyn Nesbit (Jessica Molly Schwartz) whose jealous lover killed another man over her, or “Henry Ford,” in which the famed inventor and businessman, played by Jeff Gurner, details his methods, or, in Act Two, when Jewish immigrant Tateh (Frank Mastrone), now styled as film impresario Baron Ashkenazy, sets forth the rationale of “Buffalo Nickel Photoplay, Inc.”, or when Younger Brother (Jacob Sundlie), from the New Rochelle family, gushes over “The Night Emma Goldman Spoke at Union Square”—Goldman, the fierce anarchist, is played with gutsy force by Mia Scarpa. These songs do much to maintain Doctorow’s effort to incorporate news stories and such newsworthy individuals as escape artist Harry Houdini (Christian Cardozo), African-American intellectual Booker T. Washington (Brian Demar Jones), and tycoon J. P. Morgan (Bill Nabel) into a narrative of how the New York area could both empower ambition and destroy dreams.

Mother (Juliet Lambert Pratt)

McNally’s plot centers on Mother (Juliet Lambert Pratt), as she’s the lynchpin that brings together the immigrant story and the African American story. As a conscientious society lady, Pratt is a high caliber asset of the show, showing both a wifely detachment from her paternalistic husband (Dennis Holland) and a willingness to follow the burgeoning attachments that form when she lets them. Her heartfelt rendition of “Back to Before” is a highpoint of Act 2 and she seems born for the period costumes by Diane Vanderkroef.

Sarah (Soara-Joye Ross)

Finding an abandoned black child in her garden, Mother takes in the orphan and eventually Sarah (Soara-Joye Ross), the child’s distressed mother, as well, then abets the child’s father, ragtime virtuoso Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (Ezekiel Andrew) as he pays courtship. That’s the uplifting story of Act 1, brought to rapturous realization in the duet between Ross and Andrew, “Wheels of a Dream,” that feels like an Act 1 curtain but isn’t. Additional elements are Mother’s dignified flirtation with Tateh as both, with their respective children—charmingly enacted by Ari Zimmer and Ryan Ryan (or Hannah Pressman)—take a train out of New York. The anti-immigrant hostility of the times—and ours—creates a struggle for Tateh while the virulent racism endemic to the U.S. delivers an insult to Coalhouse through the destruction of his prized Model T. by volunteer firemen.

Tateh (Frank Mastrone) and his daughter (Hannah Pressman)

As Act 2 opens, newly radicalized Younger Brother, a fireworks manufacturer, is helping Coalhouse and his followers to blow up things in a wave of anti-capitalist, antiracist terrorism. The carnage is offstage, which lets us overlook Coalhouse’s violence, while a jarring act of violence aimed at Sarah threatens to derail the busy story. As Sarah, Soara-Joye Ross delivers Act 1’s “Your Daddy’s Son” with such incredible power that we may well be disappointed to learn what the plot has in store for her. So it goes. The story drives toward its benign vision of children—white and black, Jew and gentile—playing together agreeably, though the fact that the nonwhite parents are looking on from heaven might give us pause.

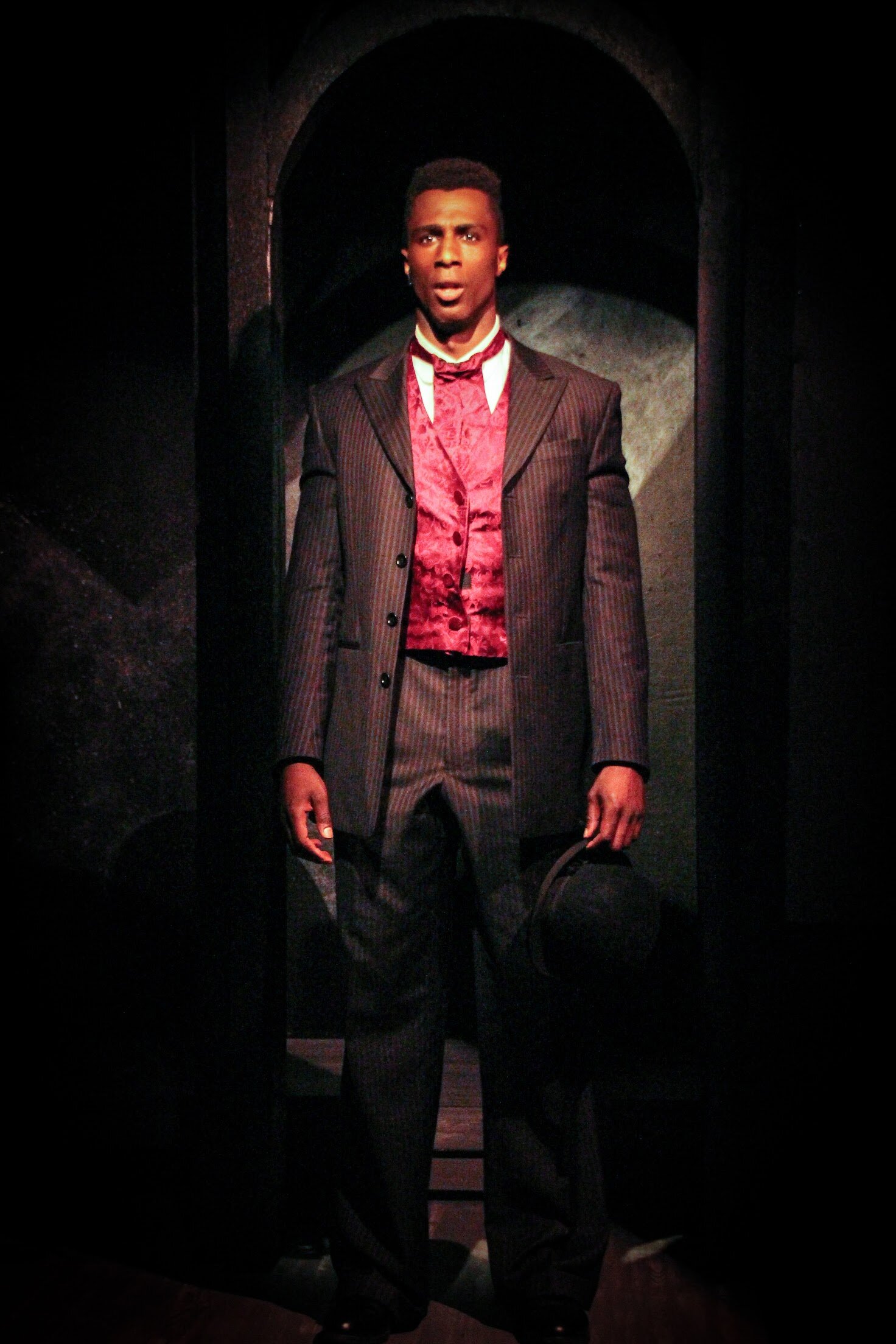

Coalhouse Walker, Jr. (Ezekiel Andrew)

As Coalhouse, Ezekiel Andrew plays both pride and humility that become righteous indignation. He has great energy and a big voice, which helps greatly in a production where sometimes the pianos overpower the singers—not helped (when I attended) by some issues with the mics that created static and seemed to lose some singers in the big choral numbers. Soara-Joye Ross and Juliet Lambert Pratt add greatly to the vocal strengths on hand, with Kanova Latrice Johnson delivering Act 1’s impassioned closer, “Till We Reach That Day.” Frank Mastrone is more endearing as Baron Ashkenazy than as Tateh whose beard only serves to look remarkably fake. Jessica Molly Schwartz does well with an ironic rendering of Evelyn Nesbitt’s obvious cheesecake function, and Broadway veteran Bill Nabel adds the requisite patrician sangfroid to J.P. Morgan, even when his beloved library is being held for ransom. As Booker T. Washington, Brian Demar Jones has plenty of panache, and Christian Cardozo’s Houdini, we might imagine, would like to escape into a show where he’s something more than a famous Italian American.

Father (Dennis Holland), seated, and his son (Ari Zimmer) and the male cast of Ragtime

Finally, a word about Dennis Holland as Father. This is a role that could easily be a joke. One moment he’s off to the North Pole with Robert Peary, then he’s receiving a frosty welcome to his home, now a nursery, where an African American couple he never met is plying ragtime and romance in the parlor; later, he has to make man-to-man chat with Coalhouse while playing well-meaning hostage, but not before he takes his son out to a ballgame for some filial bonding, only to find it’s overrun by the kind of crass American types our culture never tires of caricaturing (the song, “What a Game,” is a moment of light fun in the overwrought Act 2). Ultimately, Father goes down with the Lusitania! Through it all Holland maintains the thoughtful dignity of someone who just doesn’t get it yet knows there is something to get. It’s just that, for a little while at least, he thought he had it. All. It’s a nicely rendered character-turn in a show more concerned with songs than characterization.

Once again, MTC’s Kevin Connors shows what can be done on a small-scale with shows that could easily overwhelm a less resourceful director. His love for theater shows in every aspect of this involving Ragtime. The intimacy of staging makes this show of many moving parts—there’s even a makeshift Model T involved—even more moving.

Ragtime, The Musical

Book by Terrence McNally

Music by Stephen Flaherty

Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens

Based on the novel Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow

Directed by Kevin Connors

Musical Direction by David Wolfson

Scenic Design: Jessie Lizotte; Lighting and Projection Design: RJ Romeo; Costume Design: Diane Vanderkroef; Sound Design: Will Atkin; Props Design: Merrie Deitch; Wig Design: Will Doughty; Fight Choreographer: Dan O’Driscoll; Production Assistant: Charlie Zuckerman; Musical Staging: Chris McNiff; Stage Manager: Jim Schilling

Musicians: David Wolfson, conductor/piano; Mark Ceppetelli, second piano

Cast: Ezekiel Andrews; Christian Cardozo; Ari Frimmer; Jeff Gurner; Dennis Holland; Kanova Latrice Johnson; Brian Demar Jones; Frank Mastrone; Bill Nabel; Juliet Lambert Pratt; Hannah Pressman; Soara-Joye Ross; Ryan Ryan; Mia Scarpa; Jessica Molly Schwartz; Jacob Sundlie

MTC Mainstage

Music Theatre of Connecticut

September 27-October 13, 2019