Review of Straight White Men, Westport Country Playhouse

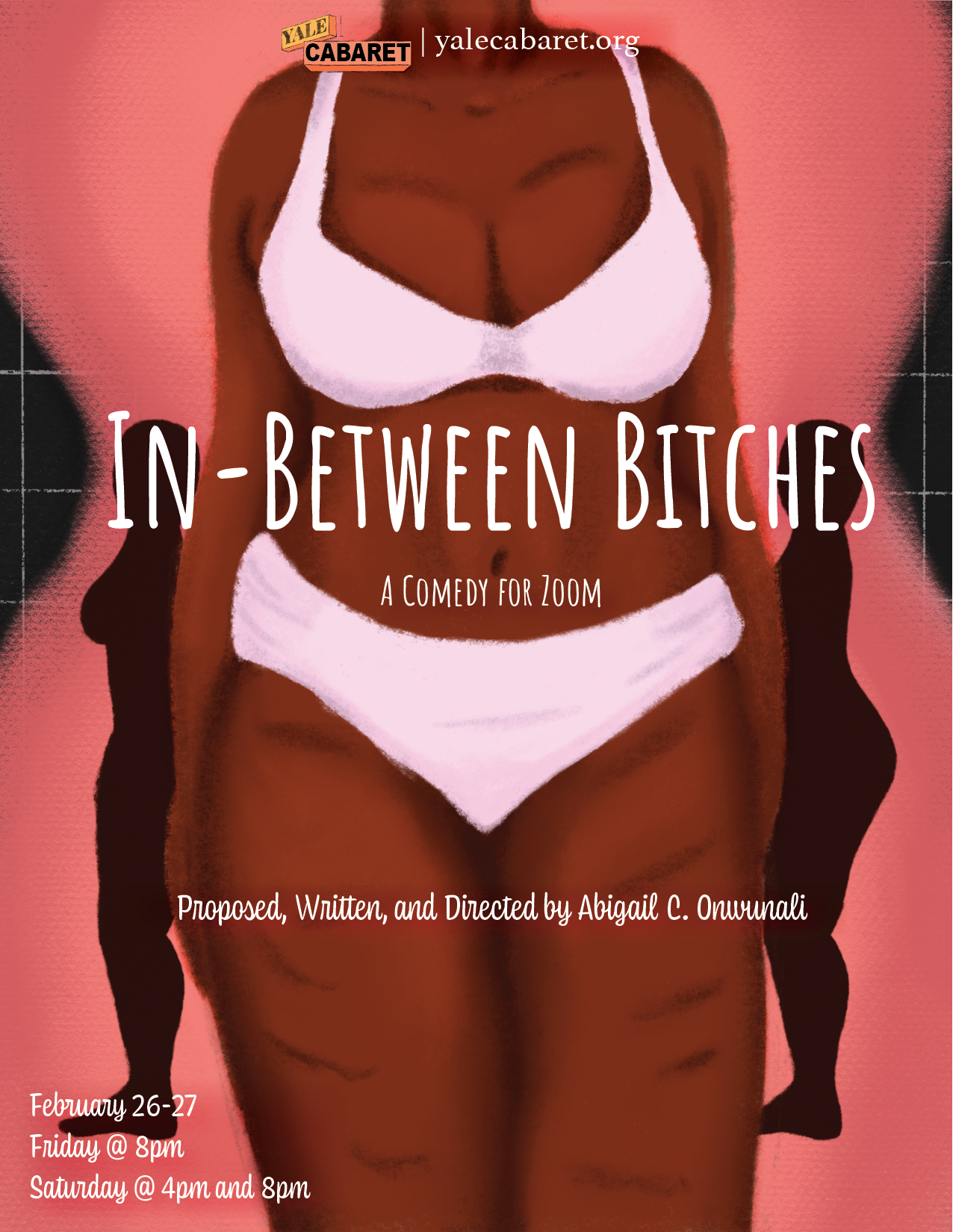

Young Jean Lee writes provocative, entertaining plays, usually with an off-kilter or oddly conceived angle. Straight White Men, now playing at Westport Country Playhouse, directed by Mark Lamos, can stand as a prime exhibit. The play first opened in New York, Off-Broadway at the Public in 2014, directed by Lee; then was revised and produced at Steppenwolf in Chicago in 2017 and in California in 2018, and then went to Broadway (the first Broadway show by an Asian American woman) in 2018. A critic’s darling of Off-Broadway, Lee has concocted a play that is almost “straight” itself: seeming to be a straight-forward story of male-bonding and dysfunction at Christmas—how much more all-American can you get?

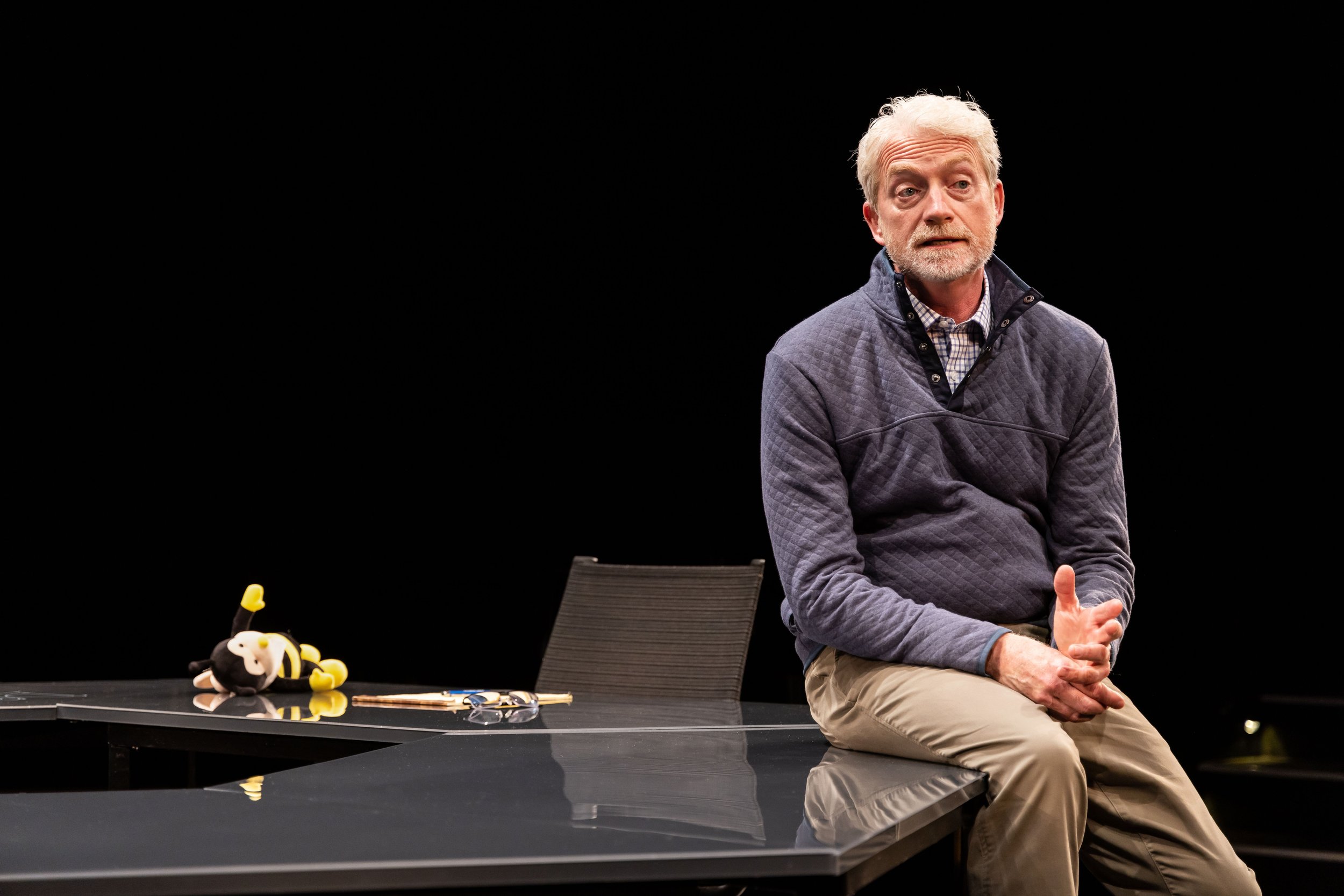

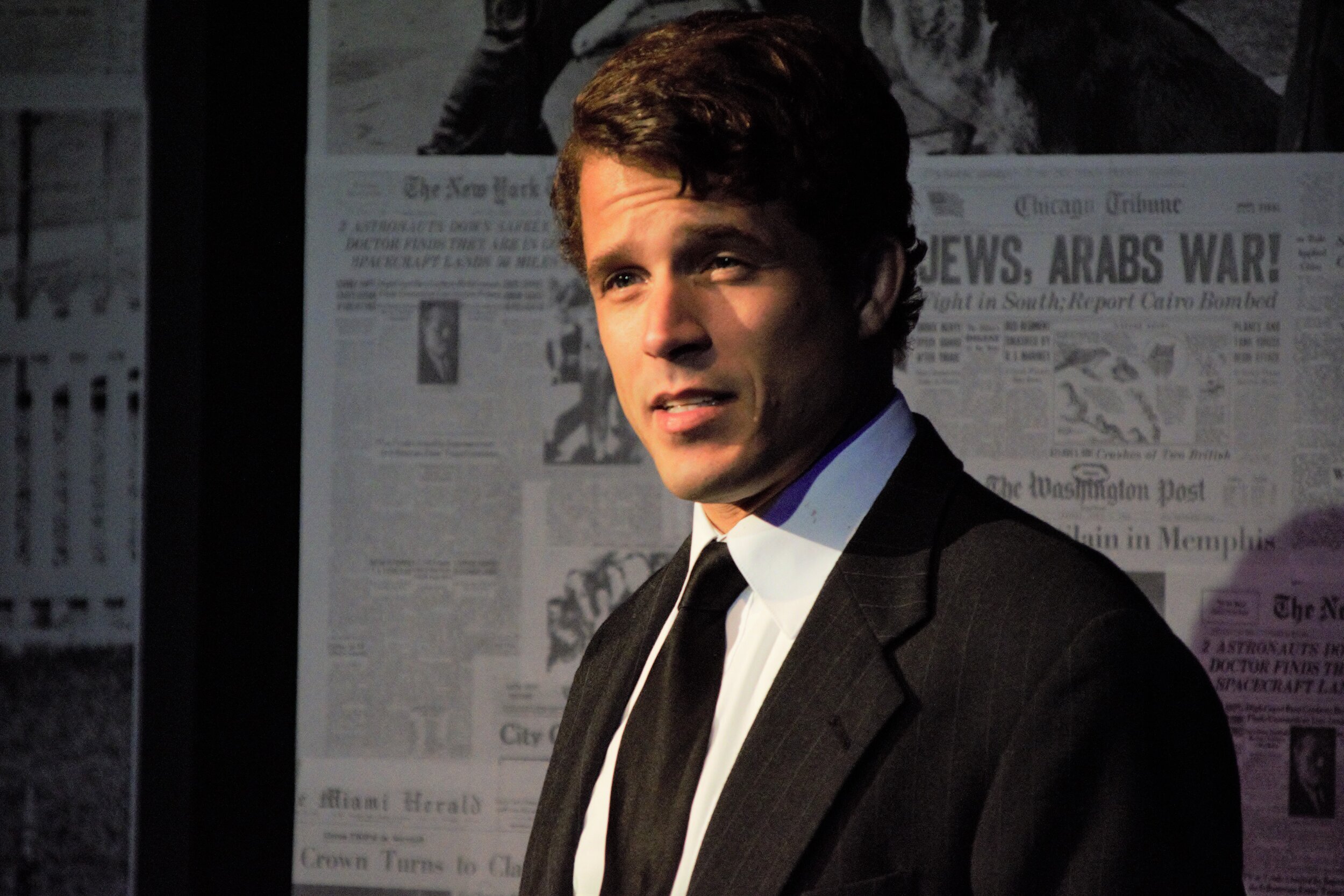

Richard Kline as Ed, Nick Westrate as Drew, Denver Milord as Matt, Bill Army as Jake in Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men at Westport Country Playhouse, directed by Mark Lamos (photo by Carol Rosegg)

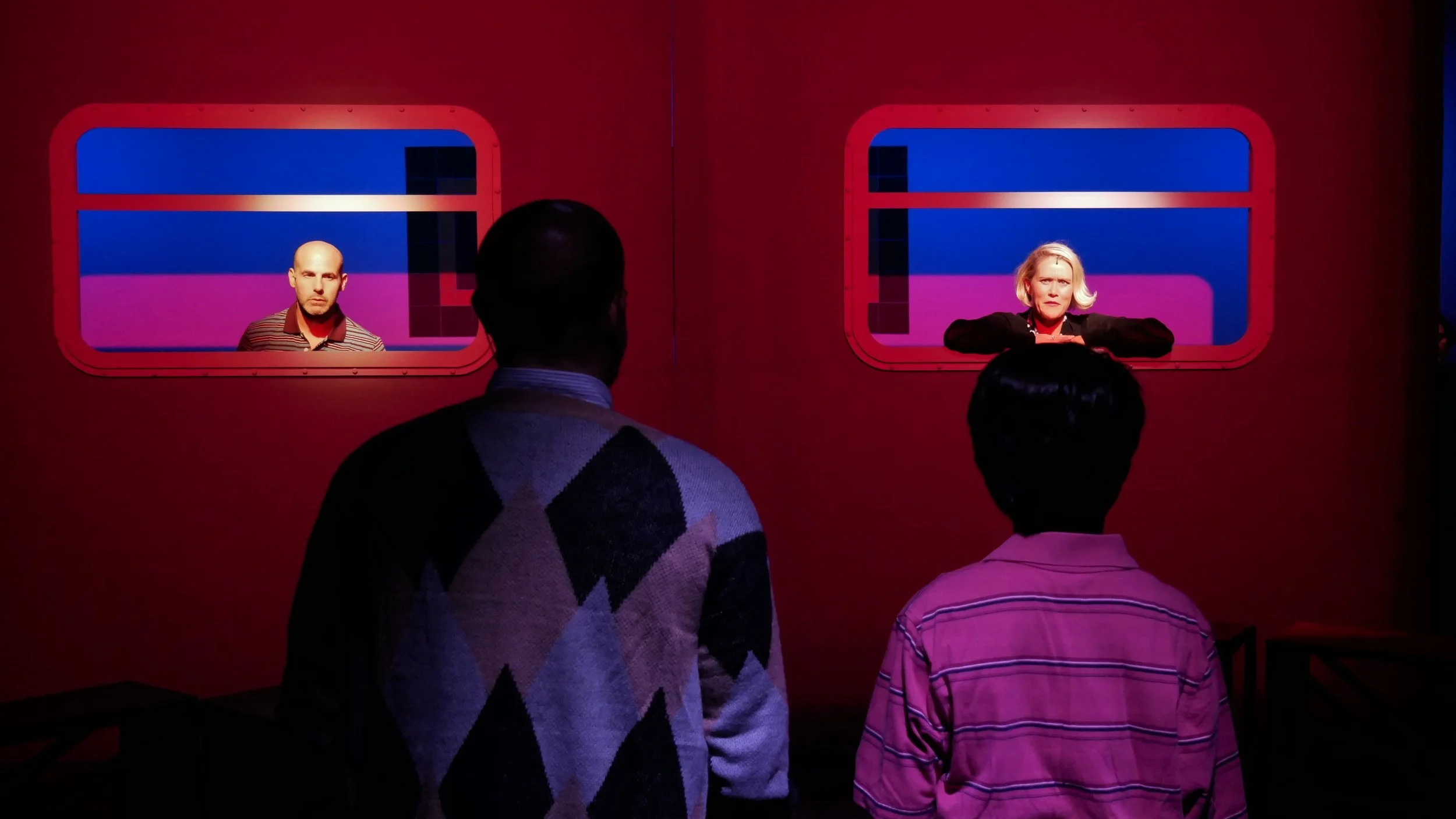

To make sure we know this is a Lee play, we’re given a sort of intro. Before the play starts we’re meant to experience club music—recorded by non-white, non-straight performers—at deafening levels while two “Persons in Charge” circulate through the audience, welcoming, chatting, handing out earplugs if required. As the play begins, the charming and elegantly attired “Persons”—Akiko Akita, non-binary, of Japanese descent, and Ashton Muñiz, gay and African American—take either side of the stage and clue us in, to make sure we understand that, in the script’s words, “the show is under the control of people who are not straight white men” (perhaps there is a place where theater is the province of straight white men, solely or mostly; if so, I haven’t been there this century). It all seems a bit precious, quaint even, but achieves Lee’s effect: we perceive her irony toward her characters and the familiar methods of theater’s make-believe, and we should be aware that we’re watching what she calls in the playbill “an identity-politics show.”

So the unshakable notion that people are best understood through tags about sexual orientation, gender, and racial characteristics (particularly pigmentation) is put before us as defining, a way of turning the tables on the privilege of whiteness and straightness and maleness as the default perspective of American culture, so that now it can be labeled, just like everyone else.

Ashton Muñiz, Person in Charge, Denver Milord as Matt, Akiko Akita, Person in Charge in Young Jean Lee’s Straight White Men, Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Carol Rosegg)

The play concerns three grown brothers visiting their father at Christmas, and is set in Dad’s basement, a man-cave complete, in Kristen Robinson’s wonderfully detailed set, with a half-bath and a washer-dryer, TV, couch, recliner and video-game console. Lest we think we will be dwelling in this cave with Neanderthals who never heard tell of a perspective “other” than straight, white and male, Lee makes sure we grasp how educated and accomplished these fellows are: Drew (Nick Westrate), the youngest, is an award-winning novelist and teaches at a college; Jake (Bill Army), the middle-child, is a successful banker who married, fathered children with and is now divorced from an African American woman; and Matt (Denver Milord), the eldest, graduated from Harvard where, for a time, he participated in a program to build houses in Ghana, and is celebrated by his younger siblings for his teenage penchant for satire (we get a glimpse of his comical send-up of Oklahoma! as a paean to white supremacy); and Ed (Richard Kline), their dad, is a widower who fondly recalls how their mother repurposed Monopoly into a board game called Privilege (pass go, pay $200 to the community chest for being white) to help make sure her brood wouldn’t “grow up to be assholes.”

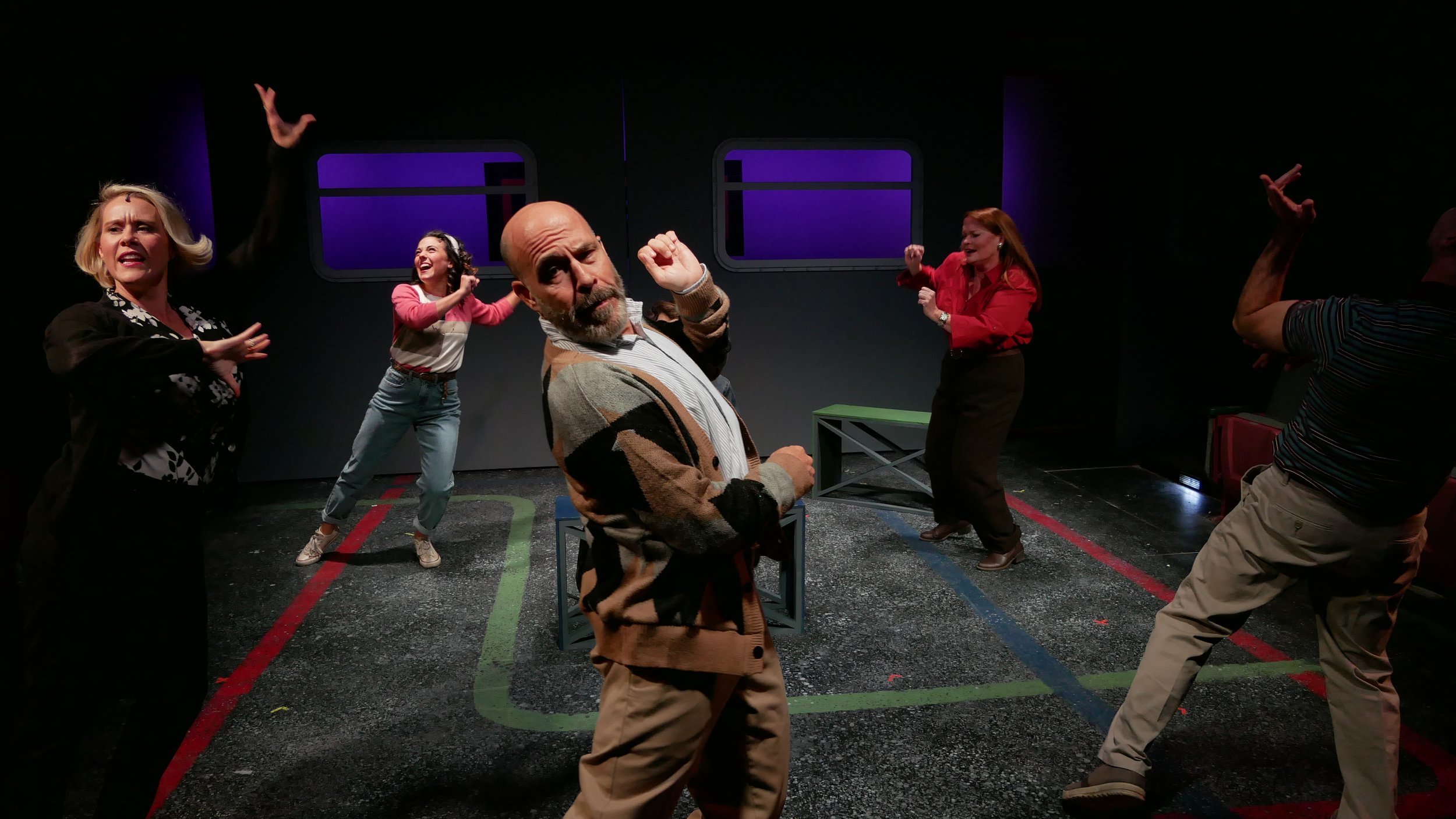

Not assholes, no, but not exactly grown-ups either. Regardless of their accomplishments, back at home the trio tend to revert to kidstuff: horseplay, rough-housing, ritual humiliations of one form or another, and of course mock disco routines, all of it vigorously choreographed by Alison Solomon. It’s conventional enough to lull us into a form of sitcom cheer where we suppose the jockeying among the lads is going to eventually become a celebration of sensitivity or some kind of crisis of identity. It mostly is the latter, but Lee doesn’t end there in quite the usual way.

Bill Army as Jake, Nick Westrate as Drew, Denver Milord as Matt, Richard Kline as Ed in Straight White Men, Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Carol Rosegg)

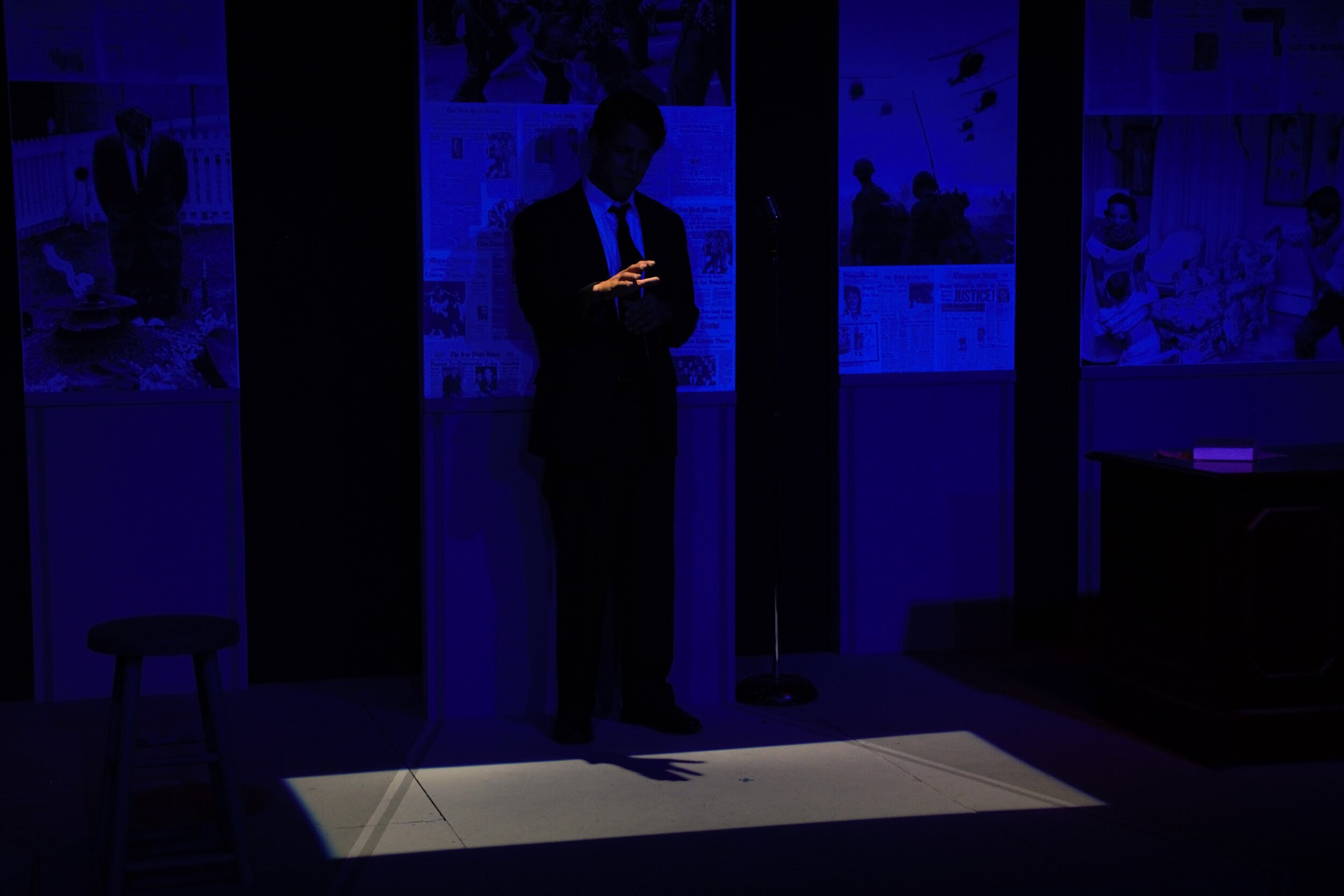

At the heart of the play is the question of the status of Matt. In the midst of a plaid-PJs-clad dinner of Chinese takeout on the couch, Matt starts sobbing, briefly. This raises a flag that will exercise the other three men, particularly his two younger brothers, throughout the rest of the play. Why is he not happy? Why is he, the one considered the most promising, wasting his time as an office assistant for a progressive organization, living at home with Dad while trying to pay-off his student debt?

The interpretations thrown at Matt’s predicament tend to make his refusal heroic—in Jake’s comically earnest view, Matt is rejecting success as a noble effort to let lesser-privileged Others have their day—or drastic—in Drew’s view, as someone who figured it all out with the aid of a therapist, Matt needs professional help. Ed is not so sure, even if he sees the notion of “helping Dad around the house” to be more of a dodge than a necessary task. Matt, for all his insistence that he’s fine, is also clearly uncomfortable with having to account for himself to the guys. A “mock interview” scene lets us see that he’s just not willing to speak the lingo of self-promotion they demand of him.

And that’s when the “identity-politics” show becomes “identity-crisis” show: all these guys know is what they have achieved; they are who they are because they can be described—professionally, sexually, racially, demographically, and so on. Matt, at this point, doesn’t know who or what he should be. We see that he has taken on the quiet domestic and office tasks generally associated with females in the work force, but he’s not deliberately making a case for that. It’s just the level that he’s at, right now. Is he too old and accomplished for a “gap year”? Is the danger of him becoming what the guys call “a loser” (aka, a slacker) too much for them to handle?

Yes, in the sense that none of them can deal with this version of Matt, his not living up to their expectations becomes the bummer that taints the party of privilege. Whatever a “straight white male” is, he can’t just drop out of it without throwing shade.

Nick Westrate as Drew, Bill Army as Jake, Denver Milord as Matt, Richard Kline as Ed in Straight White Man, Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Which reminds me there’s another meaning to the word “straight,” beyond questions of sexual orientation: in comedy the “straight man” is the one who doesn’t get hit with the pie, the one who isn’t wacky and zany and given to the tropes that desperately seek a laugh. It may be that these white straight men in Lee’s play are just now learning the joke’s on them.

What makes Lee’s approach work is the charm of it all—even if quaint, it’s cute. And so we can let her Brecht-lite be just that. It’s not about remaking theater or smashing the bourgeoisie or even ending the dominance of straight white men in our politics and worlds of business and finance and law. It’s just a ploy to make us chuckle about representation as the weird act of faith it tends to wind up as, theatrically speaking. Lee’s play offers a fun night of theater, directed with great panache by Lamos, and played with affectionate verisimilitude by its cast. Straight white men and those who—despite everything—still love them will likely be amused and touched.

Denver Milord as Matt, Nick Westrate as Drew, Bill Army as Jake in Straight White Men, Westport Country Playhouse (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Straight White Men

By Young Jean Lee

Directed by Mark Lamos

Scenic Design: Kristen Robinson; Costume Design: Fabian Fidel Aguilar; Lighting Design: Masha Tsimiring; Composer/Sound Design: Michael Keck; Choreographer: Alison Solomon; Fight Director: Michael Rossmy; Props Supervisor: Sean Sanford; Production Stage Manager: Shane Schnetzler; Assistant Stage Manager: Allie York

Cast: Akiko Akita, Bill Army, Richard Kline, Denver Milord, Ashton Muñiz, Nick Westrate

Westport Country Playhouse

May 24-June 5, 2022