Review of The Square Root of Three Sisters, at International Festival of Arts & Ideas

The International Festival of Arts & Ideas in New Haven ended on Saturday, and I closed out the events with a viewing of The Square Root of Three Sisters, conceived, written, and directed by Dmitry Krymov and created and performed by Dmitry Krymov Lab and the Yale School of Drama. It was not only the end of the show’s run, and of the festival, but a last hurrah—and first post-graduation assignment—for a number of fine actors who graduated this May from the Yale School of Drama.

To begin with: Square Root is not a play in any conventional sense. It’s theater, conceived as an event that takes place with, as Krymov says, “the seams showing.” Before the show even begins, the cast is on hand, organizing cardboard rectangles to create the playing space, all while the Iseman theater’s workroom, with arrays of tools and implements, is on display.

The performers play actors as well as characters in the piece, which uses props and costumes sparingly. The purpose of the approach, it seems to me, is to let us—and that “us” includes actors, director, crew, the Lab, and viewers—look at Chekov’s landmark classic Three Sisters from a variety of perspectives, never forgetting that the process of theater alters and adapts whatever the playwright creates.

So it’s key to the vision of this work that a playwright be present. Krymov imports Kolya Trigorin, the sensitive and avant-garde playwright from Chekov’s The Seagull, to open the show. Aubie Merrylees, who has brilliant comic timing, is well-chosen to play the nervy, breathless Trigorin, eager to get everything just right—including paper rolls to be adorned by the cast with strips of black tape to create white birches. As he literally sets the scene—with cardboard boxes suggesting different places referred to in Three Sisters—and bosses his fellow cast-members, a minor error gets corrected by a painfully loud, distorted and autocratic voice. In that moment, Krymov references the power play of theater. The director calls the shots. The actors—and Chekov himself, to the extent that Trigorin is a figure for him—must submit.

With that said, there’s a further aspect that comes to light as Trigorin, and later, the actors themselves, narrate the backstory of Chekov’s characters. Three Sisters and its world come to seem a real world where fiction has created not characters, but actual people. To deviate from which sister—Olga, the spinster/teacher; Masha, the unhappily married wife; Irina, the youngest who might yet marry—is which, or who the suitors are, would be to alter the unalterable. The characters in Three Sisters seem folkloric in so indelibly stamping the imaginations of generations of theater-goers, especially but not only in Russia.

Annelise Lawson, Annie Hägg

What can we still learn about them? What will Krymov’s approach show us? Many things, indeed. It’s a breath-taking show in its variety and imaginative flights, in its use of technical features—such as the beautiful moment when the cast discovers inside boxes lit from within the military overcoats that are their costumes, each with a character-determining tag—and even “YouTube” videos. And so much depends on the routines each actor performs in turn, routines that establish for us not only a particular Chekovian character but also, to some extent, the actor’s relation to that character.

All begin seated around a large wooden work table, and that table becomes a center, a stage upon the stage, where the incredibly ripe passions of the work display themselves. Early on, in a dialogue both charming and freaky, a teapot moves about in space between would-be lovers, the relentlessly intense Vershinin (Niall Powderly) and dour in black Masha (Annelise Lawson), suggesting not only the force of their attraction but the gentility that keeps such passions at bay. Later, in stalwart Olga’s turn, Shaunette Renée Wilson’s insistent iteration “I don’t need to be loved” alternates with a distracted insistence on the mundane: “this is a fork, this is a cup,” and so on, while constantly shifting the props about on the table with increasing violence. The seething resentment at the heart of Olga, controlled by all the force of her personality, couldn’t be more powerfully rendered. Then there’s Irina (Melanie Field). Hiding beneath the table, she’s lured out by her comically timid suitor Tuzenbach (Bradley James Tejeda) and hen-pecked brother Andrey (Kevin Hourigan) with a promise to sing the songs her mother loved. Soon music begins to play and Irina, like a cat to catnip, emerges to belt out “Someone to Watch Over Me,” with Field evoking the sheer joy of a child in performance.

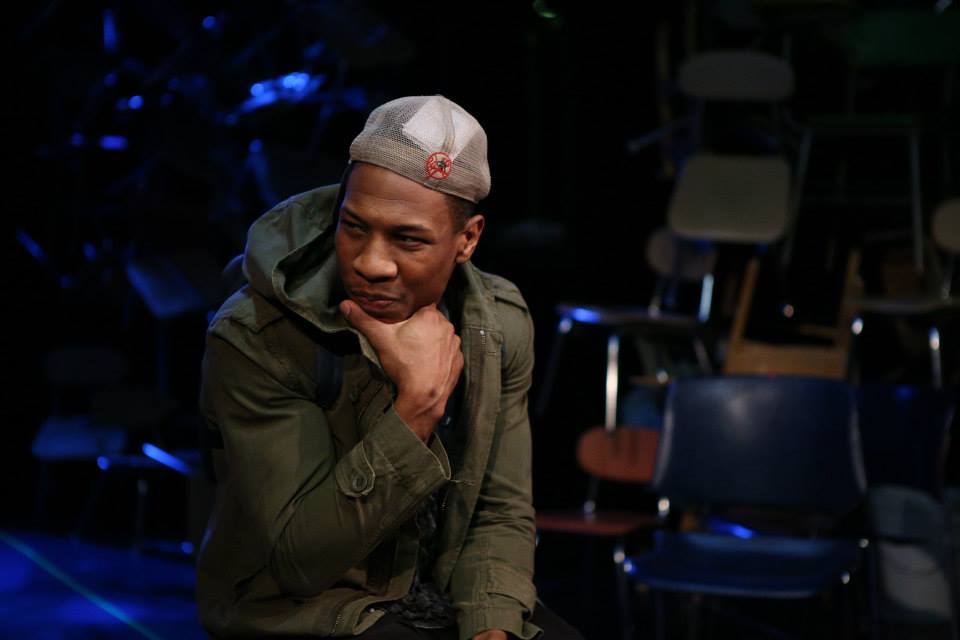

Every character gets a turn—including Julian Elijah Martinez’s dance like a constricted flame to evince the self-love and self-loathing of Solyony “who thinks he looks like” the poet Lermontov, and Annie Hägg’s table-top flouncing as Natasha, the preening and pathetically insecure wife of Andrey. At times the routines feel like improv, at other times like a physical manifestation of all that words will never convey, and even a bit like an audition for the pleasure of that ultimate watcher.

Late in the show, as a brigade of soldiers cart off all the possessions the Prozorov sisters hold dear, the table becomes a life-raft the sisters cling to and the base for the automaton they become. Along the way, the autocratic voice—which by now has begun to feel like a call to emergency evacuation or of military invasion—demands “give me a new Masha.” There follows a comical scene, nonplussing enough for anyone who hasn’t made the cut, in which Hägg, formerly Natasha, now shrugs her way into the role of the most dramatic of the Prozorov sisters while Lawson, stricken, pouts. Vershinin, however, won’t make the switch and still pines for Lawson as Masha. At this point, it’s not simply a question of how a character is conveyed by a performer, but how a performer takes over a character.

Shaunette Renée Wilson

So, when Wilson is replaced—by “that writer”—as Olga, she resists on the basis of her stature and commitment. Both of which, we sense, is her downfall. The very commitment of actor to character must be undermined. This isn’t about personalities, it’s about art aligning with the mailed fist of history. All are expendable, all are replaceable. And anyone can inhabit our treasured myths of tradition, or join the plaintive voices of the Three Sisters figurine on perpetual exhibit upon its pedestal.

A show for those who love their theater freewheeling and speculative, The Square Root of Three Sisters makes us wonder why we feel the need to have people dress up and pretend to be other, non-existent people—in other words, it makes you wonder a lot about theater and performance. In putting onstage the interplay of concepts of character, of actors as characters, and of actors as individuals, Square Root kicks against the text while scripting dissent and suppression, and manifesting an abundance of some intangible thing we lamely call “theater magic.”

International Festival of Arts & Ideas presents

The Square Root of 3 Sisters

World Premiere

Conceived, written, and directed by Dmitry Krymov, based on plays by Anton Chekov

Created and performed by Dmitry Krymov Lab & Yale School of Drama

Creative Team: Choreographer: Emily Coates; Performance Coach: Maria Smolnikova; Production Designer: Valentina Ostankovich; Sound Designer: Pornchanok (Nok) Kanchanabanca; Lighting Designer: Elizabeth Mak; Projection Designer: Yana Birÿukova; Production Stage Manager: Emely Selina Zepeda

Performers: Melanie Field; Annie Hägg; Kevin Hourigan; Annelise Lawson; Julian Elijah Martinez; Aubie Merrylees; Niall Powderly; Bradley James Tejeda; Shaunette Renée Wilson

Video Performers: Lucy Gardner; Mary Winter Szarabajka; Remsen Welsh

Artistic Staff: Assistant Director: Luke Harlan; Associate Production Designer: An-Lin Dauber; Associate Production Designer: Claire DeLiso; Puppet Designer: Matt Acheson; Fight Director and Dance Captain: Julian Elijah Martinez; Videographer: Lisa Keshisheva; Senior Interpreter to Dmitry Krymov and the Production: Tatyana Khaikin

Iseman Theater

June 21-25, 8 p.m.