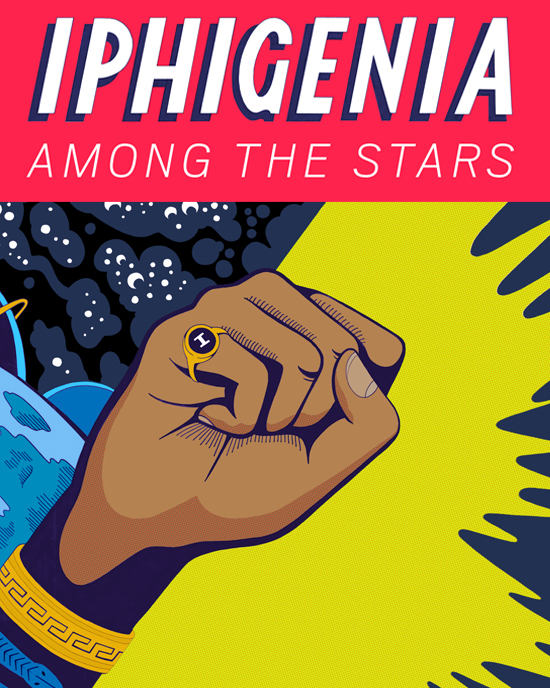

About fate they were never wrong, the ancient Greeks. In Euripides’ two plays centered on Agamemnon’s ill-fated daughter Iphigenia, as adapted into Iphigenia Among the Stars by Jack Tamburri and Ben Fainstein of Yale School of Drama and now playing at the Iseman Theater, fate decrees, first, that Iphigenia must be sacrificed so that the Greek fleets may depart Aulis for Troy, then that Iphigenia should, in Tauris, serve Artemis, the goddess who, in some versions of the story, spared the girl’s life. Certainly, we might say that human life is at the mercy of the gods, but, in the Greek system of things, even the gods must bow to necessity (or ananke).

The problem with ancient Greek drama, generally, is that it seems so…ancient. Its view of human affairs is not much encountered in our contemporary world—except in the Space Operas popular in science-fiction and fantasy films, and in comic books. Only in outlandish “other worlds” can characters—with a straight-face, as it were—speak of their own existence with the pomposity of personages who, in the Greek view of drama, were truly above and beyond the common run of mankind. The happy high concept of Tamburri’s Iphigenia is that it marries a telling grasp of the plays to staging, costuming, and set-design right out of Star Trek by way of the Marvel Comics Universe.

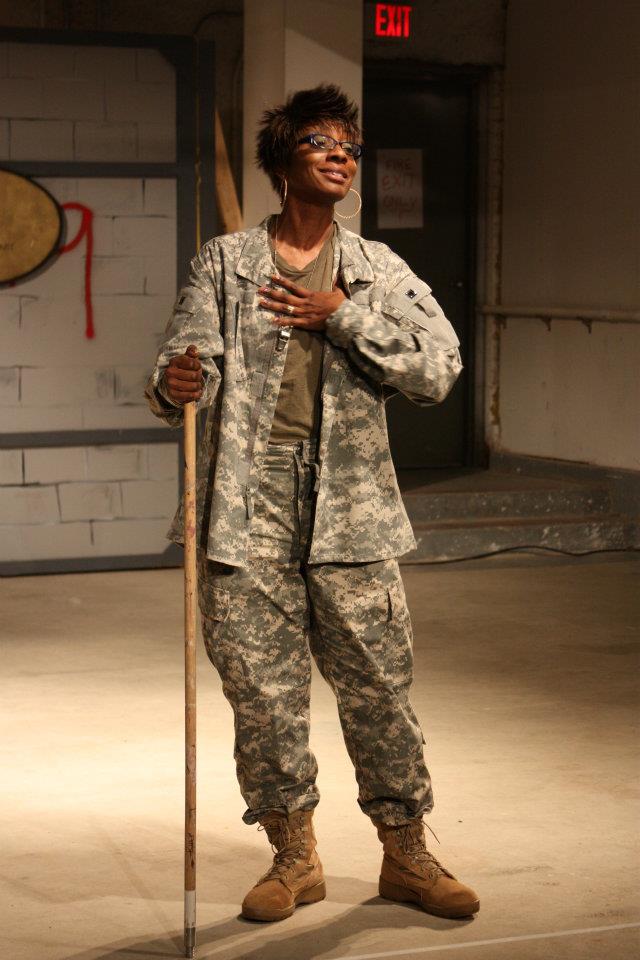

That may sound like a cue for campy take-offs of B-movie matinees featuring the likes of Steve Reeves or some other muscle-bound clod (like that Austrian weight-lifter turned actor turned governor), but that’s not the way Tamburri and company play it. And the production wisely places Iphigenia at Tauris before Iphigenia at Aulis—so we get a more comic Act One before a heavier Act Two—thus allowing Iphigenia Among the Stars to end, more or less, with Iphigenia’s show-stopping speech in which the heroine (Sheria Irving, truly transported beyond this instant) concedes the need for her own death.

The plot is indeed served by this interesting arrangement of parts, but let’s talk about the design. This is one you have to see for yourself. The set and costumes go a long way to transport us to the feel of a Star Trek episode (the original series, in the Sixties)—the be-glittered Chorus (Ashton Heyl, Marissa Neitling, Carly Zien) seem like they should open with “when the moon is in the seventh house and Jupiter aligns with Mars”—an effect helped by references to “the Oraculons.” And when we finally meet Thoas, the King of Tauris (Winston Duke), we see a creature that seems to move like an animatronic illustration. The Marvel Comics aesthetic is well-served not only by the colors (I don’t know what to call the blue worn by Orestes (Mamoudou Athie) and Pylades (Paul Pryce) but the Comix-lover in me loved it) but especially by an arch above the stage upon which projections (Michael F. Bergman) recreate at times the “background panels” of comics. The projections also add a comic Comix touch to the moment when Achilles (Athie again, in successively more absurd—impressively so—costumes) thumps the ground with his fist, sparking some “clobberin’ time” animation. And when shestalks into her temple at the end of Act One, Artemis (Ceci Fernandez) looks a bit like that big Destroyer thing Loki sent to earth to beat-up Thor, and sounds like a goddess on steroids.

And that’s just some of the fun on view. Did I mention how much I loved the capes worn by Agamemnon (Pryce) and Menelaus (Duke)? OK, now I did. And check out the canary yellow gown with black accents on Clytemnestra (Fernandez). Then there’s the language itself—Thoas’ mannered utterances pleased me to no end, as did Chris Bannow, both as a Herdsman beside himself with TMI, and as an Old Slave more charming than The Robot on Lost in Space who has to “compute” the contrary and counterfactual messages he must deliver. A real high point, in Act One, is the trenchant stichomythia between Iphigenia and Orestes leading to a truly affecting recognition scene. Tamburri makes sure his cast makes the most of such question-and-answer exchanges—a comical instance takes place later in Act One between Thoas and Iphigenia, when the latter is stealing away with the temple icon.

As Iphigenia, Irving takes us through many changes—from the no-nonsense priestess ready to sacrifice prisoners for Tauris, to the softened sister of Orestes, ready to risk death to free him and Pylades and steal away with them, to a virginal girl, expecting to be married to great warrior Achilles, to a sacrificial figure herself, beseeching her own father for mercy, and, finally, the willing victim who, by that act, becomes something else: Heroic? Mythic? The Embodied Will of Ananke? A chick with super-powers? How about all of the above?

As Artemis, Ceci Fernandez gets to end Act One with a bang and plays future regicide Clytemnestra with the mien of a haughty Westchester County matron—she’s fun! Mamoudou Athie, as Orestes, has a long-suffering air and, in the recognition scene, a precision that helps sell it; as Achilles, he postures and pivots in skin-tight briefs, and speaks as if the famed warrior is also a self-involved asshole—much sport is had at the hero’s expense. Winston Duke, as Menelaus, is also very much into having his way, and, as Thoas, is a real treat. Paul Pryce plays good support as Pylades, and as the much-tried Agamemnon put me in mind of a certain leader of our day who has often to face a shit storm with equanimity.

In fact, the overtones of the play, for our times, seem to be about each person recognizing their own duty in the design of things. To that end, a great feature was the use of the Chorus who, at the start of Act Two, clothes in shreds and faces sooty, have to cope with their fall from the sky and from the favor of the goddess, and their return to the past to see what they can see of a different future. They, like us, look on to see how alignment with one’s fate turns on a dime, from fighting it to “the readiness is all.” And that means that we, like them, have to learn what it is what we see means.

In bringing new spin to an ancient tale, Iphigenia Among the Stars is stellar.

Iphigenia Among the Stars

Adapted from Euripides by Benjamin Fainstein

Conceived and directed by Jack Tamburri

Jabari Brisport: choreographer; Christopher Ash: scenic designer; KJ Kim: costume designer; Benjamin Ehrenreich: lighting designer; Steven Brush: composer and sound designer; Michael F. Bergmann: projection designer; Benjamin Fainstein: production dramaturg; Robert Chikar: stage manager

Yale School of Drama

October 31-November 3, 2012