Review of The Flamingo Kid, Hartford Stage

Darko Tresnjak, who steps down as Artistic Director with the conclusion of this season, ends his tenure at Hartford Stage on an upbeat note. The Flamingo Kid, a new musical based on the fondly regarded film by Garry and Neal Marshall from 1984, re-teams Tresnjak with Robert L. Freedman, Books and Lyrics, who wrote the Book and co-wrote the lyrics for the Tony-winning A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, one of the director’s prior big successes.

This time the comedy is not quite as wildly inspired, but the show is vastly entertaining, with the kind of witty lyrics—often adding a deliberate flavor of Jewish Brooklyn missing from the film—that musicals about coming of age should have. Scott Frankel, of War Paint and Grey Gardens, wrote the music and there’s a nice range of musical inspirations, all feeling at home in 1963, the year of the action. That’s the summer, of course, between the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963. A great time to be young and alive after the U.S. got the U.S.S.R. to backdown and before the country, in the view of many commentators, lost its innocence.

Steve (Ben Fankhauser), Hawk (Alex Wyse), Jeffrey Winnick (Jimmy Brewer) in Hartford Stage production of The Flamingo Kid (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The Flamingo Kid is rich with the kind of associations many of us have with the era, not least in pitting the bedrock values of the working lower middle-class, here instanced by the Winnicks in Brooklyn, with the leisure-time instincts of the upper middle-class out on Long Island. It’s still a time when such might occasionally rub shoulders, and when the so-called American Dream offered the notion that a kid who has to earn his way could still work his way up in pay and respect.

The story, which begins on the Fourth of July weekend and ends on Labor Day weekend, takes the side of the young, ethnic up-and-comer, Jeffrey Winnick (Jimmy Brewer), over the self-important blowhard Phil Brody (Marc Kudisch), owner of some luxury car showrooms, whose spell the young man falls under, while also falling for Brody’s niece, Karla (Samantha Massell). Freedman’s script takes a few potshots at those who put salesmanship over sincerity and elevate winning by any means over winning fairly. There’s even a little wink in having Karla reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique on the beach, a bit of cultural unrest that finds its answer in the actions of Brody’s wife Phyllis (Lesli Margherita) late in the play.

Phyllis Brody (Lesli Margherita) (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Indeed, one way the musical stretches beyond the movie is in its interest in the older generation. The film is concerned almost wholly with Jeffrey’s effort to prove himself, moving from the plans of his gruff but loving father, a plumber, to the slick and glib mentorship offered by Brody, “the King” of the gin game at the El Flamingo Beach Club. Freedman gives standout numbers to Mr. Winnick (Adam Heller), “A Plumber Knows,” and his wife Ruth (Liz Larsen), “Not For All the Money in the World,” and to Mrs. Brody, whose “The Cookie Crumbles” is a word-to-the-wise aimed at Karla, full of the cynicism of the neglected wife. Meanwhile, Brody gets to make the most of “Sweet Ginger Brown,” his tagline, a song that comes back for a rousing reprise in Act II.

For excitement, there are big dance numbers like “Another Summer Day in Brooklyn,” “Rockaway Rumba,” and even a visit to the track with “In It to Win It.” Gregory Rodriguez adds much pizzazz to Act II as the lead singer of Marvin and The Sand Dunes, singing “Blowin’ Hot and Cold.” Comic highlights are provided by Brody’s card-playing pals who are apt to carp at “The World According to Phil,” and by the MILFs of the day who can’t get enough of Jeffrey as the cutest “Cabana Boy.” The romantic plot is handled by “Never Met a Boy Like You,” wherein Karla is smitten, and it plays out with the sweetness of the sweetest summer romance, featuring a see-saw and a lifeguard stand and a painted moon over a painted sea.

Jeffrey Winnick (Jimmy Brewer), Karla Samuels (Samantha Massell) (photo by T, Charles Erickson)

Is the show sentimental and nostalgic? You betcha, so much so it feels like a return to an earlier time not only in its setting—which is fetchingly colorful in the set by Alexander Dodge and the costumes by Linda Cho, two longtime exemplars of excellence at Hartford Stage—but in its grasp of how to combine family and fun and romance with the kicks of kids and the fretting of elders. The movie was an Eighties’ nod to the way Fifties Hollywood informed so many of the movers and shakers of the era. As a musical in our day, The Flamingo Kid treats perennials like first love and first major summer job the way the Golden Age of television might and lets us enjoy the ride for all it’s worth.

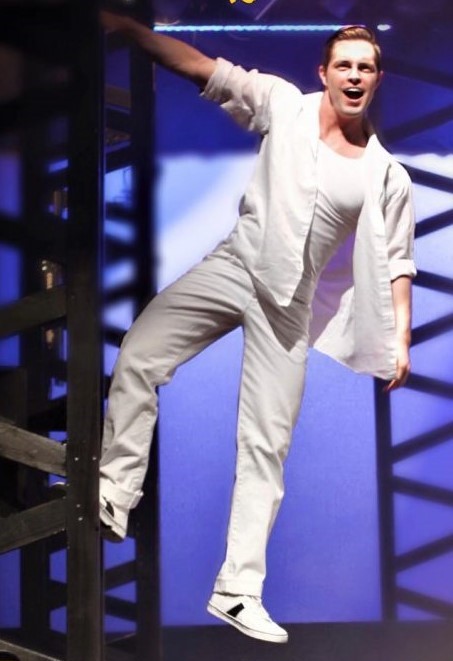

Phil Brody (Marc Kudisch) and Jeffrey Winnick (Jimmy Brewer) (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The first Act may run a bit long and, in general, there’s a sense, in each Act, that the search for a close is a problem that derives from the arc of numbers in a musical more than from the story per se. Freedman wants to keep the emphasis on “Fathers and Sons,” a theme that shows up strong at the end with the show’s penultimate number. Which makes it an ideal show running up to Father’s Day on June 16—indeed, the show has been extended from June 9, its original ending date, to June 15. Bring the folks, or the kids, as the case may be.

Jeffrey (Jimmy Brewer) and Arthur (Adam Heller) Winnick (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The show’s secondary theme—what makes for marital happiness in two couples of different socio-economic situations and how the difference affects a young, formative couple negotiating both worlds—plays out as a fond look at how much we owe to where we’re from—and how much we all love summer getaways. As a musical getaway, The Flamingo Kid is hot, and that’s cool.

The Flamingo Kid

Book & Lyrics by Robert L. Freedman

Music by Scott Frankel

Based on the motion picture The Flaming Kid, screenplay by Neal Marshall and Garry Marshall, story by Neal Marshall

Directed by Darko Tresnjak

Choreography: Denis Jones; Scenic Design: Alexander Dodge; Costume Design: Linda Cho; Lighting Design: Philip Rosenberg; Sound Design: Peter Hylenski; Projection Design: Aaron Rhyne; Wig & Hair Design: Charles G. LaPointe; Makeup Design: Joya Giambrone; Dance & Vocal Arrangements: Scott Frankel; Music Director: Thomas Murray; Orchestrator: Bruce Coughlin; Fight Choreographer: Thomas Schall; Dramaturg: Elizabeth Williamson; Production Stage Manager: Linda Marvel

Orchestra: Conductor: Thomas Murray, Keyboard: Paul Staroba; Percussion: Charles DeScarfino; Reed 1: John Mastroianni; Reed 2: Michael Schuster; Trumpet: Seth Bailey, Don Clough; Trombone: Jordan Jacobson; Horn: Jaime Thorne; Violin/Viola: Lu Sun; Guitar: Nick DiFabio; Bass: Roy Wiseman; Keyboard Programmer: Randy Cohen

Cast: Ben Bogen, Jimmy Brewer, Lindsey Brett Carothers, Ben Fankhauser, Michael Hartung, Adam Heller, Jean Kauffman, Ken Krugman, Marc Kudisch, Liz Larsen, Taylor Lloyd, Omar Lopez-Cepero, Lesli Margherita, Samantha Massell, Anna Noble, Erin Leigh Peck, Gregory Rodriguez, Steve Routman, William Squier, Kathy Voytko, Price Waldman, Jayke Workman, Alex Wyse, Kelli Youngman, Stuart Zagnit

Hartford Stage

May 9-June 15, 2019