Review of ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, Yale School of Drama

A play where the most sympathetic figures—Giovanni (Edmund Donovan) and Annabella (Brontë England-Nelson), a brother and sister—are incestuous lovers is taking risks against strong identifications. John Ford’s 17th century drama ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, a Yale School of Drama thesis show for director Jesse Rasmussen, presents a world of battling wills where betrayal and bullying are the order of the day. There are also acts of sensational violence for which the Jacobean period is well known. There are poisonings, duels, eyes put out and throats slit, and a heart impaled on a sword. At the end of the evening the point of it all may have escaped you but the sheer power of it will stay with you for a while.

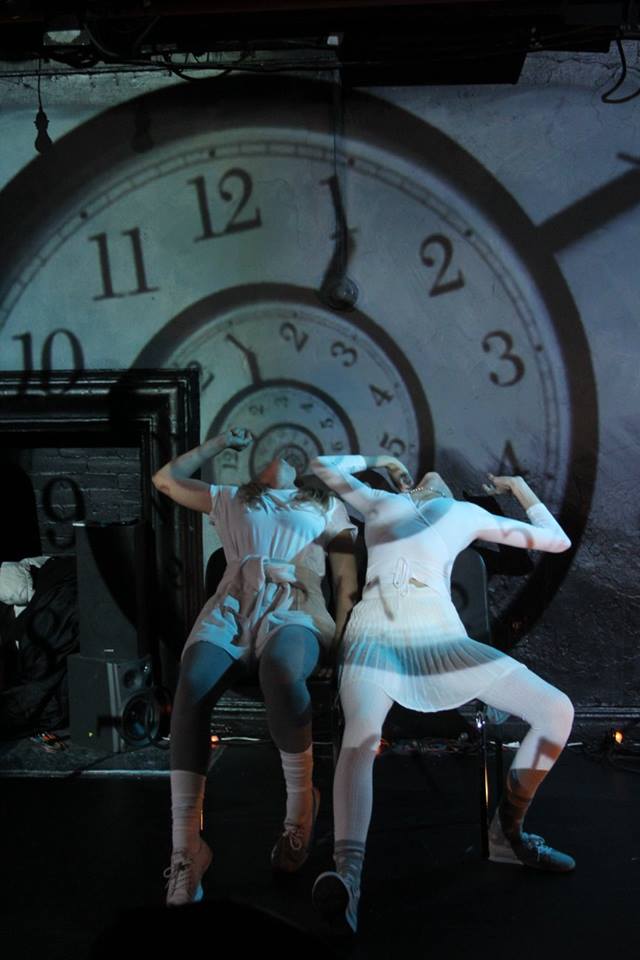

The set by Ao Li comes by way of unusual decisions, such as the audience seated on the stage in the University Theater arranged at a height that makes the majority of the seats balcony level. Down on the stage is an open playing space where most of the action takes place. But the unadorned stage is augmented by a bridge-like structure above the playing space. And stretched the length of that level is a large screen behind a clear curtain on which show projections of what happens below stage—in the intimacy of Annabella’s bed chamber. The different levels suggest a private, privileged space below the area of public skirmish and struggle on the main stage, and, above, a level where, often, characters look down on the encounters below. It all makes for a very lively staging. Indeed, the swiftness of the first part little prepares us for how much things will go awfully awry in the second part.

The main mood of the first part is of misgivings surrounding a taboo love affair between lyrical and like-minded siblings. Donovan and England-Nelson look enough alike to lend some actuality to their kinship and both play well the seriousness of the incestuous passion. Their scenes together are strong in shared feeling, particularly the scene of avowed love. And Putana (Patricia Fa’asua), Annabella’s servant, seems to take the news of the love affair in stride, suggesting that a lady may avail herself of any gentleman—father, brother, whomsoever—whenever a hot mood strikes. Her rather lusty presence adds a lightheartedness to the early going. Even the Friar (Patrick Foley) in whom Giovanni confides could be called tempered in his displeasure at the youth’s chosen object of desire. There are also somewhat comically hopeless suitors for Annabella’s hand, such as Grimaldi (Ben Anderson), though Soranzo (George Hampe), the one favored by Annabella’s father Florio (Sean Boyce Johnson), has a preening, wheedling quality that could prove troublesome.

Soranzo has troubles of his own though. Hippolita (Lauren E. Banks), whom he has jilted, vows revenge and enlists Vasques (Setareki Wainiqolo), Soranzo’s serving-man, to help her achieve her goal, in return for sexual favors. The character of Vasques is key to both plots as he foils Hippolita’s plan, causing her death instead of Soranzo’s, and also learns, by cozening Putana, of the affair between Giovanni and Annabella and the latter’s pregnancy. Played with steely, scene-stealing charm by Setareki Wainiqolo, Vasques is almost an Iago-figure; though not nearly so malevolent—for malevolence’s sake—he is the most aware of how to gain advantage from the weaknesses of others.

The other malevolent character, Hippolita, is given convincing vicious authority by Lauren E. Banks and her death scene is the most dramatically rendered. Patricia Fa’asua’s Putana, a simple pawn ultimately, gets a memorable scene of degradation that is almost the final judgment of the play: Putana’s complicity could be said to be innocent of any selfishness and her penalty a final outrage. Which is then surpassed by a grandly telling final tableau of Annabella.

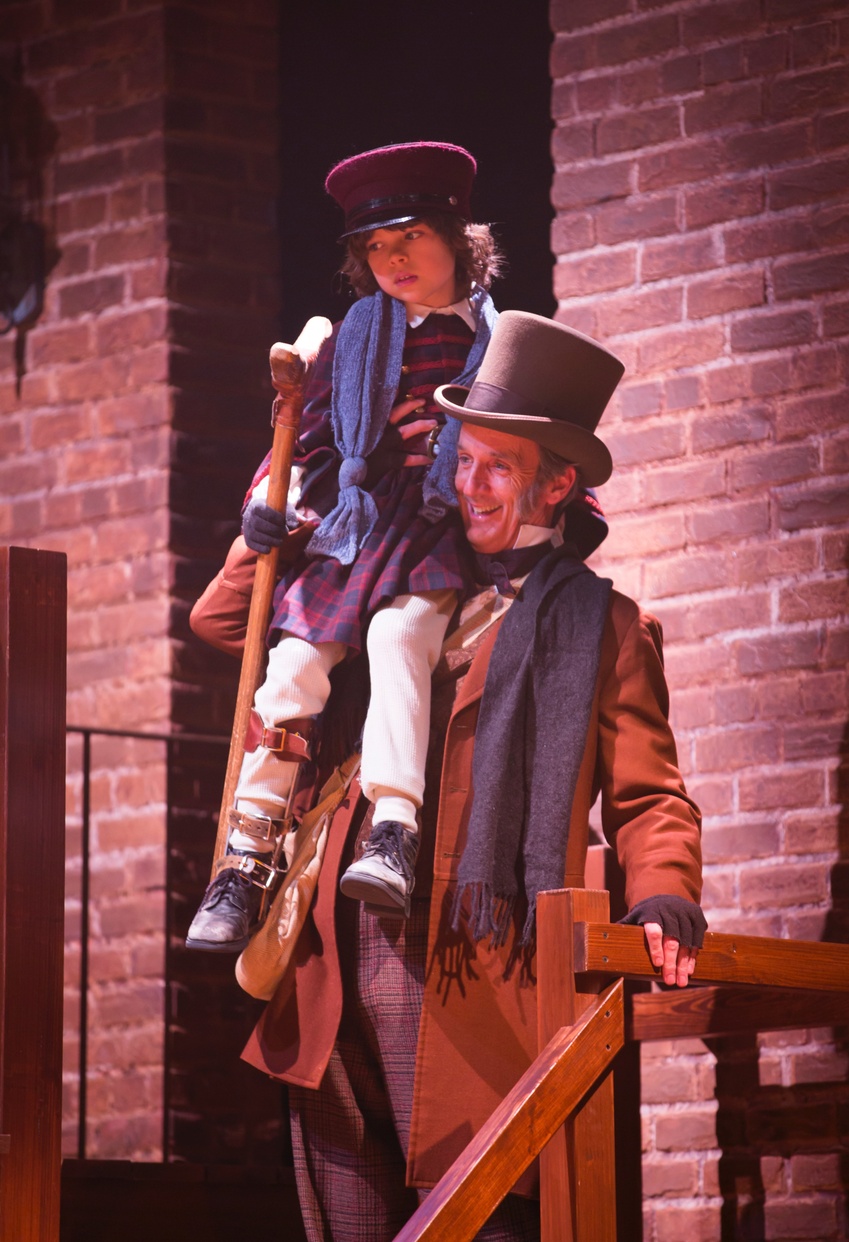

As our hero, Giovanni, Edmund Donovan can work up his passions well, and the love scene between him and Annabella, like her death scene, is made almost cinematic by the means that relay these scenes to us. George Hampe’s Soranzo is a mass of nervous energy, a privileged dastard who, as in some ways the main figure linking both fatal plots, is deplorable and fun. Sean Boyce Johnson, Patrick Foley, and Ben Anderson—as a grandly pompous Cardinal—all fill their roles with aplomb. As Annabella, Brontë England-Nelson shines the brighter for how brief is her joy and how inevitable her death—“Love me or kill me, brother,” she tells Giovanni, so of course he does both. Her most poignant moment is a song of heartfelt misery that describes the pathos of any true love in this wickedly cruel society. There are also beautiful songs of high-minded clerical detachment, rendered by the Cardinal’s Man (Christian Probst) in angelic tones.

The music and sound design from Frederick Kennedy are key to the emotional tone here, which, like Sarah Woodham’s costumes, is somewhat subdued, even solemn. Erin Earle Fleming’s lighting design gives all an even tone, but glare on the sheet covering the screen showing John Michael Moreno’s projections creates a distancing effect to frustrate our voyeurism in viewing Annabella’s chamber, which contains as well a pet bird. When not fronting projections, the sheet seems a gore-spattered curtain suitable to Ford’s theatrical world.

Though Rasmussen and dramaturg Davina Moss have arrived at a very playable text, cutting characters and subplots to keep our focus on the sibling lovers, ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore still comes across as more sensational than satisfying. Its provocations lack a sense of the savagery of our era, so that it seems a deliberate jolt for the jaded tastes of another day. “All are punished!” the Prince exclaims at the close of Romeo and Juliet, the Shakespeare play to which Ford’s play is most akin, and here that is certainly true as well, though with something more of the scorecard of blood-letting one finds in slasher films.

’Tis Pity She’s a Whore

By John Ford

Directed by Jesse Rasmussen

Choreographer: Emily Lutin; Scenic Designer: Ao Li; Costume Designer: Sarah Woodham; Lighting Designer: Erin Earle Fleming; Sound Designer: Frederick Kennedy; Projection and Video Designer: John Michael Moreno; Production Dramaturg: Davina Moss; Technical Director: Tannis Boyajian; Stage Manager: Sarah Thompson

Cast: Ben Anderson; Lauren E. Banks; Edmund Donovan; Brontë England-Nelson; Patricia Fa’asua; Patrick Foley; Isabella Giovanni; George Hampe; Sean Boyce Johnson; Christian Probst; Setareki Wainiqolo

Yale School of Drama

January 31-February 4, 2017