Review of Trevor, New Haven Theater Company

Nick Jones’ Trevor, playing tonight for one more show at New Haven Theater Company, directed by Drew Gray, is a rollicking comedy that gets progressively darker. It’s not a bait and switch so much as it’s an absurdist situation that gets real, with potentially unpleasant consequences.

Sandy (Sandra Rodriguez) lives in an apartment that looks as if she shares it with a hyperactive child, filled with toys and activities and stuff not picked up. But her “child” is actually a chimpanzee named Trevor (Peter Chenot) who is getting perilously close to full grown. Like any protective and attached mother, Sandy wants to minimize any problems with her growing “boy.” But as the play opens he has just driven her car to a Dunkin Donuts and back, depositing the auto on the lawn of neighbor Ashley (Melissa Smith). All of which is handled comically as Jones—by giving us access to Trevor’s inner thoughts—keeps us entertained with the monkey business of how a reasonably intelligent chimp might interpret the intentions of humans upset with him. Trevor’s a walking comic aside on everything going on around him, so that the stress we see in Sandy and Melissa, also a mom, becomes a kind of satire of clashing versions of parenting. Water off the duck’s back of Trevor’s self-obsessed charm.

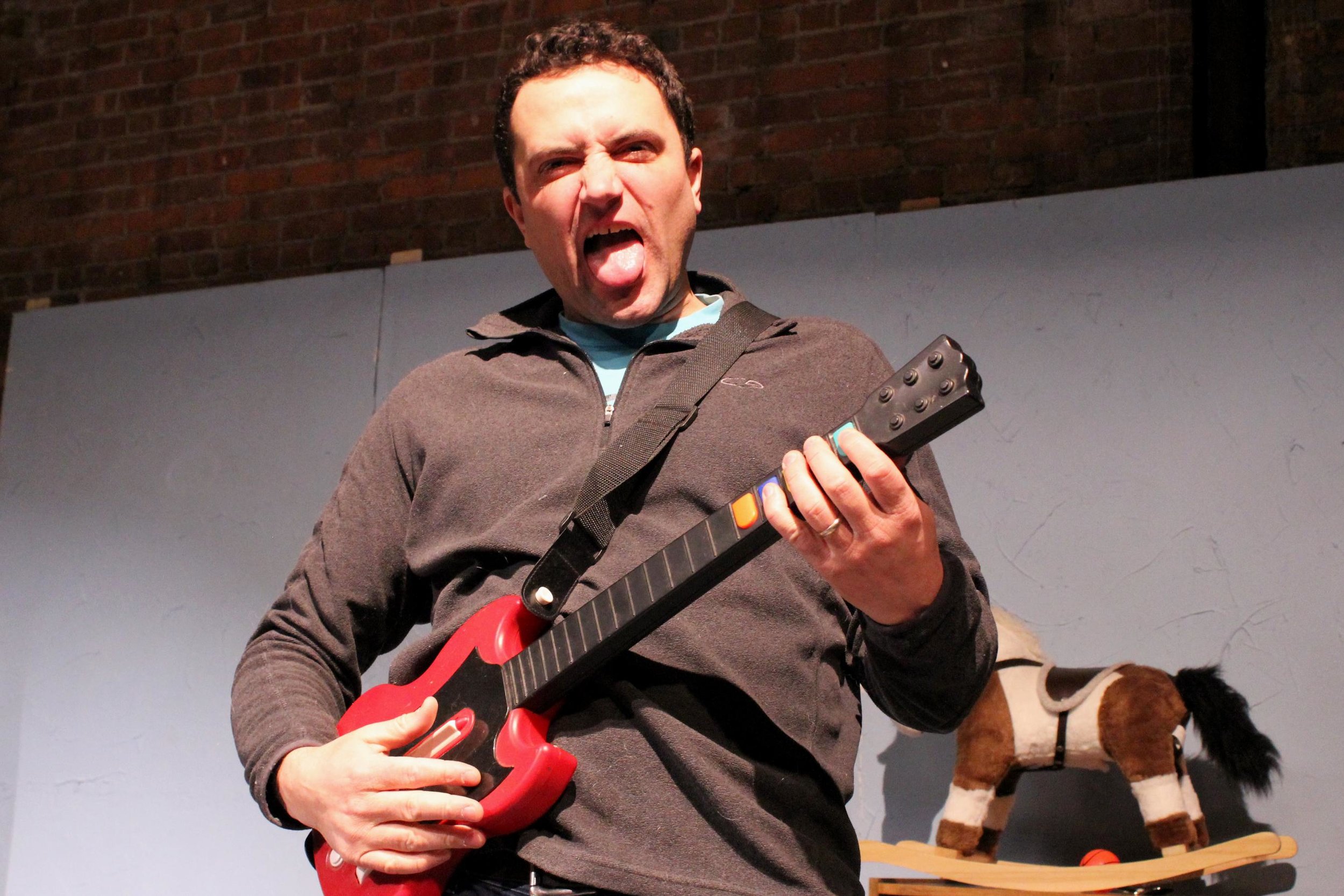

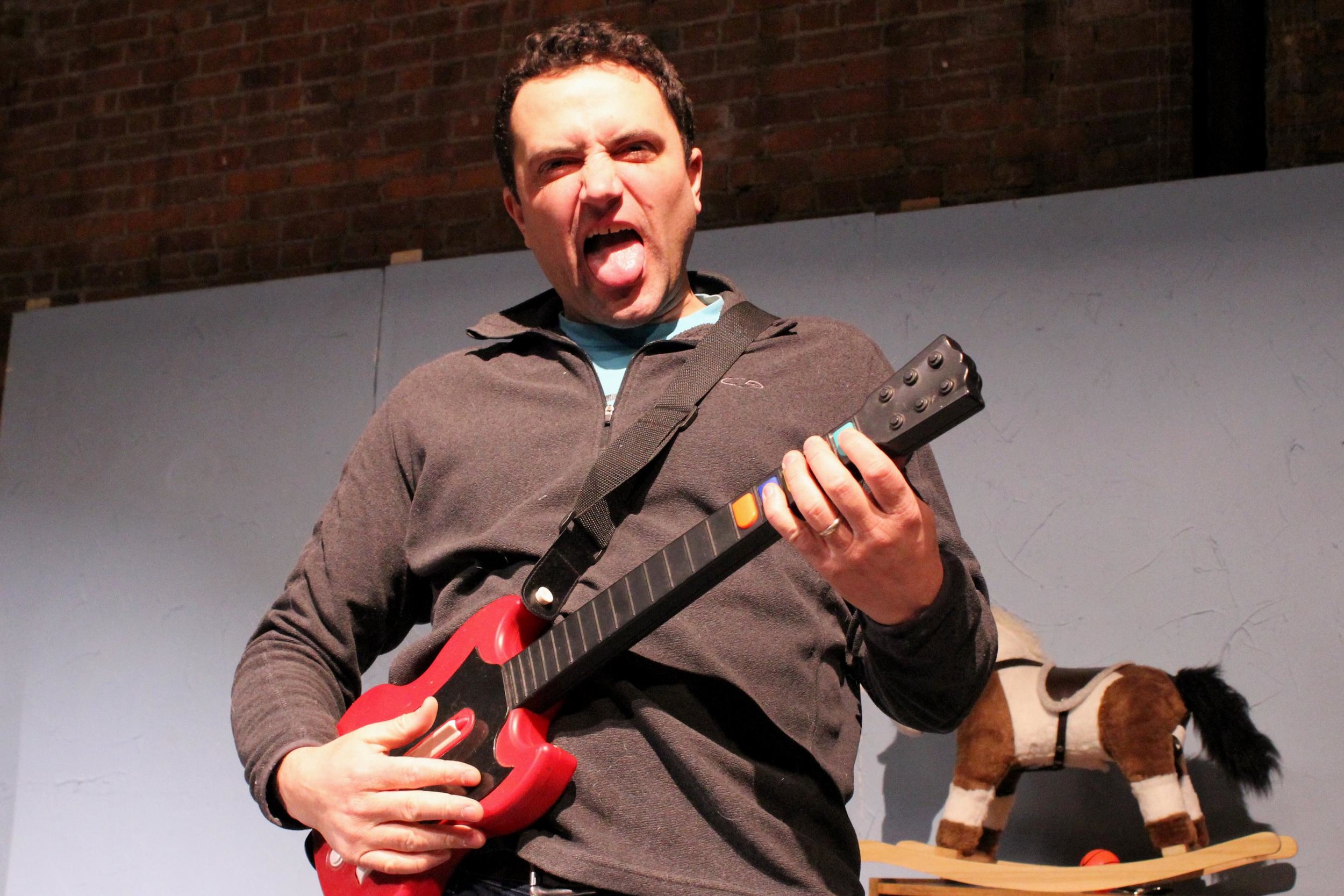

Trevor (Peter Chenot)

The comedy is further given a sizeable shot in the arm by the fact that Trevor isn’t just any chimp. In his glory days he was on TV with no less a star than Morgan Fairchild (played in Trevor’s memories and daydreams by Susan Kulp) and he’s convinced that Hollywood will come calling any minute. He also experiences fantasy interactions with Oliver (Trevor Williams), a success story of a chimp who gets to wear a white tux and claims to have a human wife and half-human kids. The interactions between Oliver and Trevor about the monkeyshines of show biz let Trevor take aim at more than domestic dysfunction. The heartache of out-growing home-life is set beside the heartbreak of any minor talent trying to become “somebody.” All this is handled with a light touch by director Gray and company, and in a wonderful manic-slacker manner by Chenot.

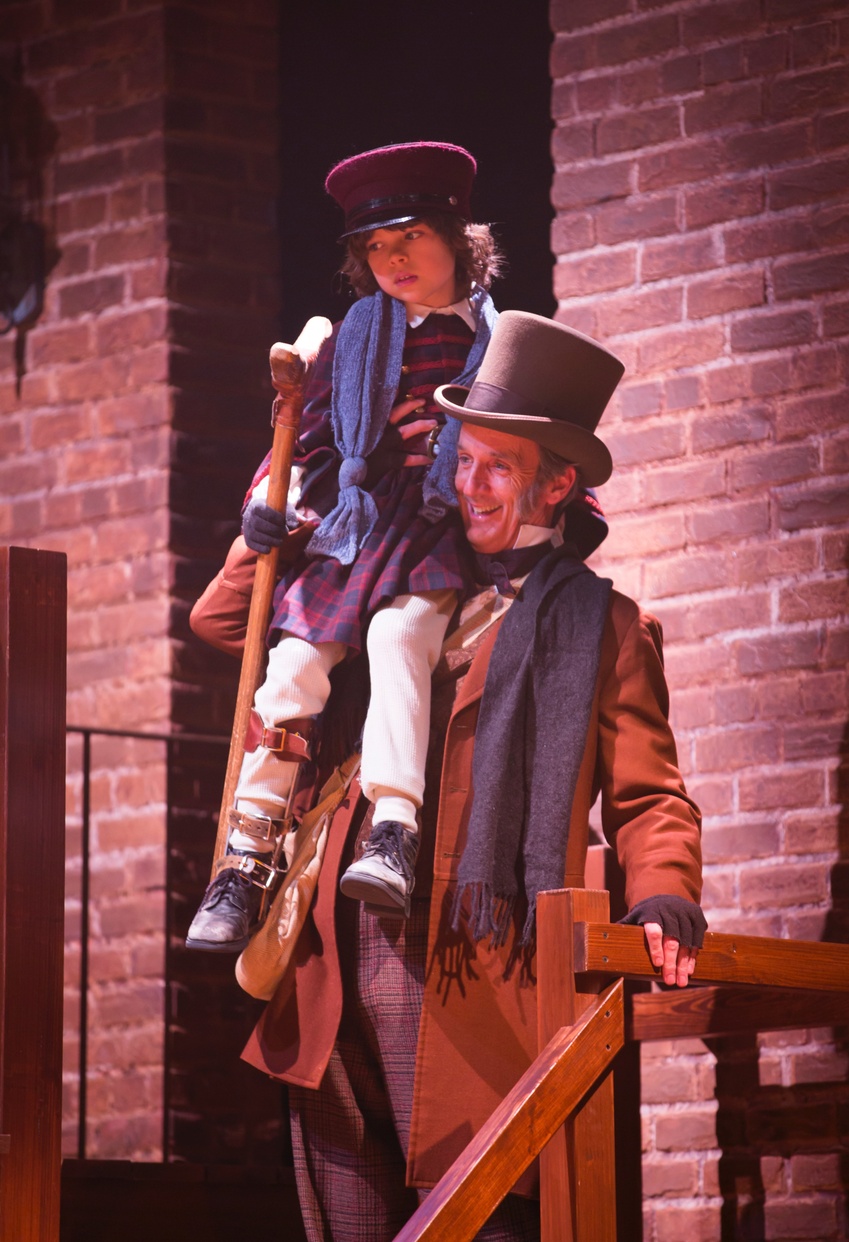

How real living with Trevor will become is a question that starts to rear its head when a visit by a police officer (Erich Greene) to Sandy’s home, provoked by Melissa among others, opens up the question of whether Trevor has become a public safety issue (clearly he has, but Trevor is a kind of “local color” celebrity who has been given plenty of leeway, until now). This intervention leads to a visit by Jerry (Chaz Carmon), from an animal protection agency, to evaluate the situation. Carmon gets a lot of mileage out of looking both agreeable and frightened out of his wits at the same time, while Rodriguez begins to let us see the desperation at the heart of Sandy’s plea to be left in peace with her child-pet. The end result is not likely to be what anyone really wants, and that’s real life alright.

Along the way there’s lots of fun with Trevor’s delusions of grandeur, including a glimpse of Morgan Fairchild aping a chimp and, later, surrendering to Trevor’s charms, and with Trevor’s bag of tricks, such as rollerblading and playing toy guitar. Pathos comes from the well-meaning monkey’s efforts to control a situation he doesn’t understand. The scenes without Trevor tend to be a bit flat, lacking the comic intrusion of his point of view, as if Jones couldn’t be bothered to make them either believable or funny, though a breezier overall comic tone might help to sell them. When Trevor is present, the comedy of human behavior, from a chimp’s perspective, keeps the ball bouncing.

In the end, the play, while a fun time in its portrayal of a chimp a lot like us, provokes with the question of whether being humane—and what that means—defines being human. Otherwise, we’re all just a bunch of dumb animals.

Trevor

By Nick Jones

Directed by Drew Gray

Cast: Chaz Carmon, Peter Chenot, Erich Greene, Susan Kulp, Sandra Rodriguez, Melissa Smith, Trevor Williams

Board Ops: George Kulp, J. Kevin Smith

New Haven Theater Company

February 23-25; March 2-4, 2017