Review of Cry It Out, Hartford Stage

Human services. What does that phrase make you think of? Care of the sick, disabled, elderly? What about the form of care that is among the most time-consuming and anxiety-ridden: the care of newborn children. Molly Smith Metzler’s Cry It Out, now at Hartford Stage in a delightful production directed by Rachel Alderman, gets the rigors of the latter “service” exactly right, making comic drama of the way we tend to make light of all the potential heartache that comes with being the adults in the room.

The show features my earliest choice in this season of Connecticut theater for outstanding performance: Rachel Spencer Hewitt plays new mom Jessie with a voice pitched perpetually in wonderment at what’s become of her. She’s a latter-day “angel in the house,” a doting mother who nearly lost her baby pre-birth, a successful lawyer (this could be partnership year) who is learning she might rather remain at home, and sometimes she can let herself go, abetted by the brash, comic, and spot-on support of Evelyn Spahr’s Lina, the next-door new mom. This can-do duo becomes regulars in the backyard playground, a circular arena of scrappy grass beneath silhouettes of townhouses, with a graceful space between, in Kristen Robinson’s handsome set. There these breast-feeding buddies find that, despite their differences in background and paygrade, they can actually talk to each other about the one thing they both really care about: being a mom.

Jessie (Rachel Spencer Hewitt), Lina (Eveylyn Spahr) in Hartford Stage’s production of Cry It Out, directed by Rachel Alderman (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

What makes the play work so well is the way these two gifted performers, under Alderman’s feel for human foible, fully inhabit Smith Metzler’s funny and perceptive script. Jessie and Lina could be caricatures but they are knowing enough to know that, and that gives them a personal irony and exuberance that’s fun and infectious, even when they have to vent about things like Lina’s alcoholic mother-in-law or Jessie’s husband’s sudden need to have a cottage on Montauk next to his parents. The first scene plays out best simply because we’re happy to overhear the way these two outgoing women get on.

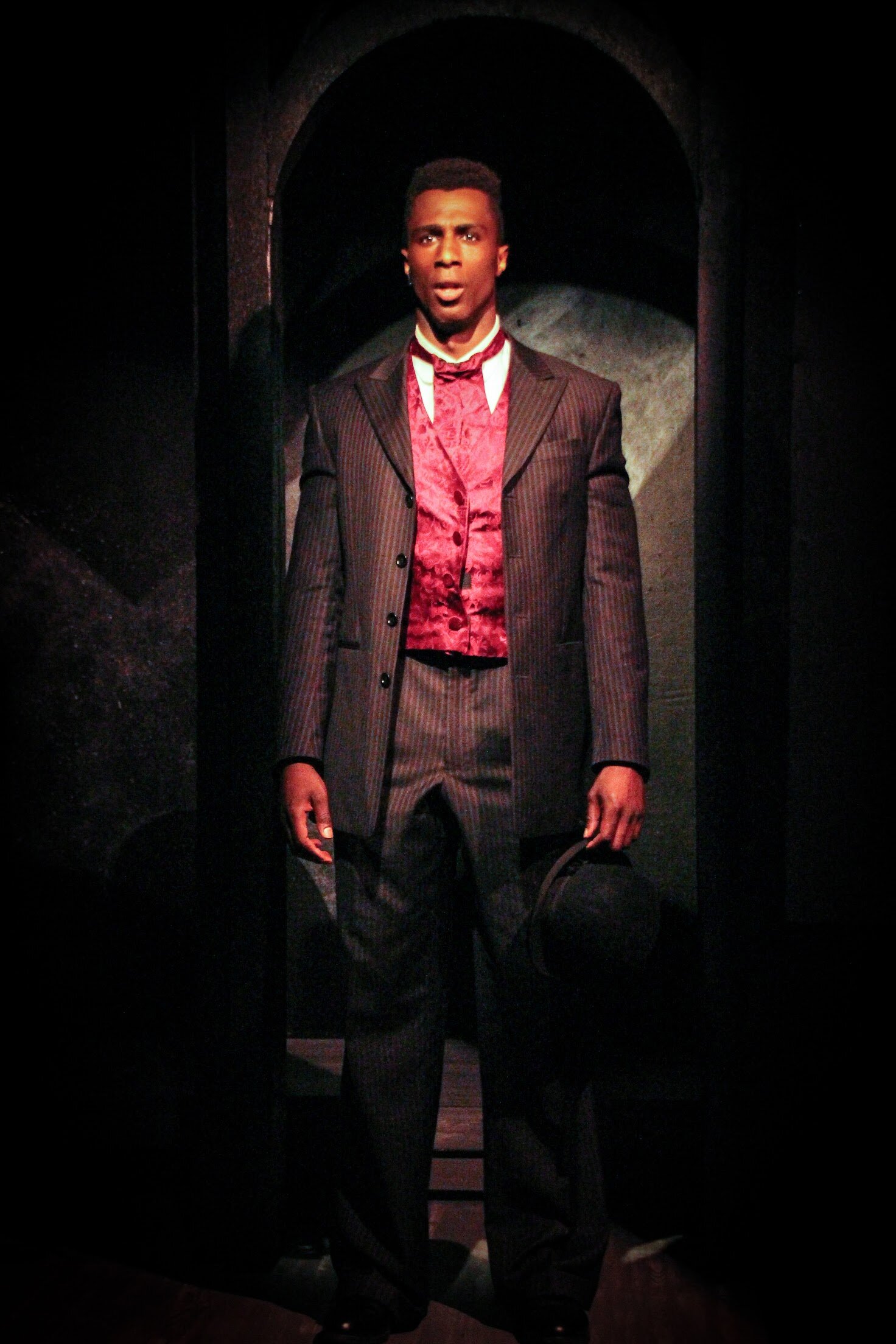

Mitchell (Erin Gann) in Hartford Stage’s production of Cry It Out (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

The complications come in two forms. One is the need to return to work—Lina’s date is already set—to keep both two-income households running, and that means the days of their joyful routine are numbered. The other is an odd request from the well-heeled neighbor up the hill. Mitchell (Erin Gann), a nice suit in a rush to make a train, barges in on them like a walking explosion of awkwardness, his gesturing hands and glancing eyes moving everywhere at once. His request: could he set up a playdate between his wife, a new mom having trouble coping (despite a support staff), and these two comfortably at-home mommies?

When we finally meet his wife Adrienne (Caroline Kinsolving), she’s the proverbial third wheel. She’s not into anything the others are into, she exudes professional froideur, and she’s exactingly rude and contemptuous. At first we might think this very successful jewelry designer is only there to be a foil, giving Lina someone to mock and Jessie someone to feel sorry about. And she is that, but she’s also going to give the requisite speech that lets us know what makes the mean girl mean. That moment, near the end, is not all it could be—Kinsolving keeps Adrienne cool even when she’s literally throwing eggs—but her speech does offer a cautionary point about stones and living in glasshouses.

Lina (Evelyn Spahr), Jessie (Rachel Spencer Hewitt), Adrienne (Caroline Kinsolving) in Hartford Stage’s production of Cry It Out (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Underneath all the banter and the angst about letting down the child is, perhaps, some idea like Tolstoy’s famed line: “all unhappy families are unique in their unhappiness.” Which is to say that not only do we all fail to be perfect parents, but that the way each of us fails isn’t something that can be fixed by some all-purpose remedy. Like the “cry it out” method of getting an infant to go to sleep, the choices parents make tend to be policed in odd ways by an implied collectivity. In watching parents with their children (or, in this case, hearing discussions of spouses and children), there’s always a detail or two that screams “socialization.” And that’s what keeps us in this game. Whether or not you are a parent, some version(s) of a parent raised you. And you wonder how it might all have gone differently.

And if you are a parent it’s hard to imagine that you won’t find much here to amuse you and maybe choke you up. In particular, Smith Metzler is able to evoke—in Spencer Hewitt’s giddy domestic rapture, self-conscious but pure—what it’s like to spend time with an infant on a daily basis. If you haven’t had that pleasure in a while, be prepared to have your memory renewed. And if you have, maybe even more so.

Jessie (Rachel Spencer Hewitt), Lina (Evelyn Spahr) in Hartford Stage’s production of Cry It Out (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Smith Metzler is also sure enough of her material—and of an audience at child-rearing age—to end with an interrogative. Many plays today try to prod us into thinking about the practices of exclusion and inclusion in our society. Cry It Out takes that question down to a basic formulation: how long should we keep our children to ourselves and how soon should we put them out there with everyone else?

Cry It Out

By Molly Smith Metzler

Directed by Rachel Alderman

Scenic Design: Kristen Robinson; Costume Design: Blair Gulledge; Lighting Design: Matthew Richards; Sound Design: Karin Graybash; Dramaturg: Shaila Schmidt; Casting: Laura Stancyzk, CSA; Production Stage Manager: Kelly Hardy; Assistant Stage Manager: Chandalae Nyswonger; Production Manager: Bryan T. Holcombe

Cast: Evelyn Spahr, Rachel Spencer Hewitt, Erin Gann, Caroline Kinsolving

Hartford Stage

October 24-November 17, 2019