Review of Rubberneck, Yale Cabaret

The Yale Cabaret is back for its second weekend in November and won’t return until December 5th. This week Rubberneck by Mattie McGarey, a New York-based choreographer and performer, brings to the Cab its second wordless performance piece of the season. Here, unlike Bodyssey, the third show of the season, narrative trajectory is less marked in favor of vignettes of movement. A cast of six, garbed in becoming outfits with pleasing color coordination (Yunzhu Zeng, costumes), move through a series of routines. Some, like the opening—in which all perform morning routines such as showering, arranging hair, dressing—contain elements of mime. Others, like one that seems to be taking place, judging by the rhythmic music, in a club, makes the six seem like parts of the same collective organism. The overall impression is of six parts of the same machine, located in separate spaces, but answerable to the same directives.

The cast of Rubberneck by Mattie McGarey at Yale Cabaret, November 14-16, 2019

The different arrangements of the six make for changing patterns, and each performer interprets the movements differently. The ad hoc cast, which includes McGarey, is drawn from Yale College, the Yale School of Music, the Yale School of Drama, and from the New Haven community. Rubberneck, the statement by the artistic team reads, “interrogates body language, symbolic gestures, and unspoken social cues as essential ingredients to the expansion and extinction of our society.” With that in mind, the repetitions can be seen as the rote movements we all perform as a means to exist in society (I won’t say simply “exist,” for who knows what that might be like?) and the personal je ne sais quoi each brings to such repetitive movements is the little friction of individuality.

The six performers often enough seem robotic, moving upon mindless tracks. The impression is strengthened by the many times the performers extend a palm in front of their faces, staring into the little screen that now dominates all social spaces. At one point, with the six sitting on chairs, each throws out looks into the social space as if trying both to be seen and to avoid seeing. Or maybe just trying to see who might actually see them. A related sequence found each slipping about on the hard vinyl chairs, trying to find some sweet spot between relaxation and vigilance, some almost falling, some never quite at ease.

There’s a heightened sense throughout the show of what it means to watch others move. If you’re the type of person who can be occupied for hours watching people in parks, train stations, airports and so on, you should find the show very appealing. There’s always new information coming at the viewer even when it works at some subliminal level, the way we—perforce—have to process whatever takes place around us. Here, the show is for our attention and yet it’s the kind of show that makes us attentive to what makes sense, what has significance, in what others do and how they look while doing it. What it means, in other words, to be a spectator is implied in everything we notice in public. “Rubberneck,” of course, refers to the way people acknowledge something untoward happening, most commonly used to describe how an accident suddenly, in the midst of the routine behavior of driving, makes us spectators again, watchers at what has happened to someone else.

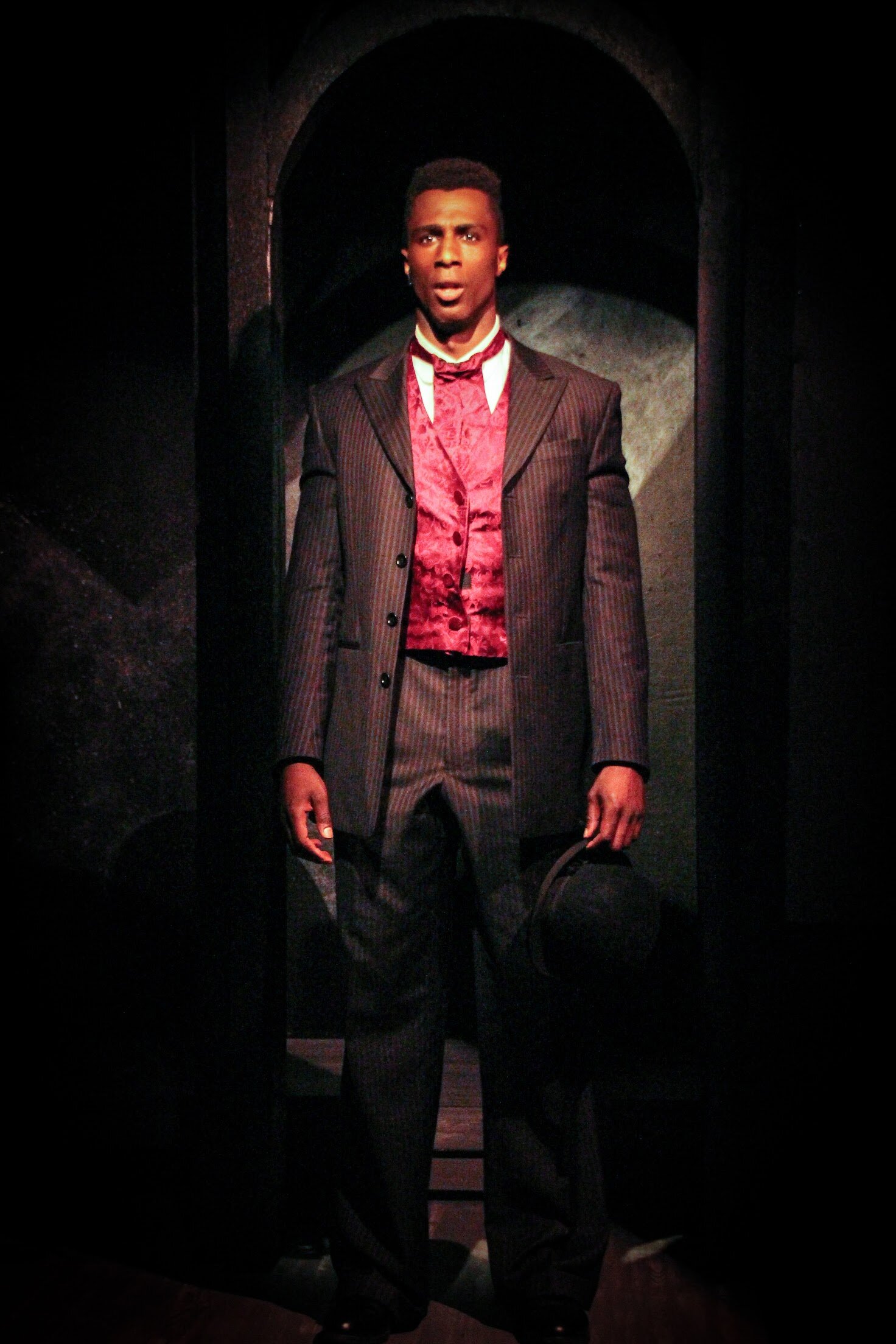

Mattie McGarey in Rubberneck at Yale Cabaret, November 14-16, 2019

Several times McGarey detaches from the simpler movements the others perform. It starts with a dramatic movement as if being ejected, in a slide across the floor backwards, while the other five stand in a sort of fortified coffee klatch. At other times, she’s apt to spiral about on the floor, creating movements with more rhythmic fluidity than the group tends to enact. There are also dispersals of the cast in ways that have an obvious symbolic logic, as when the two male performers sit off to the side as if in their own world, leaving the four female performers to work through other routines. Or a variation on musical chairs—all six walk around the line of six chairs and, in sequence, the performers break out of the rhythm to remove their own chairs, one at a time. What are the chairs? A habitation, a comfort, a personal space we each bring and take with us?

The show is greatly aided by Taiga Christie’s lighting and Bailey Trierweiler’s compositions which at times feel trancelike, at times using flurries of more anxious rhythm, at times brandishing silence as perhaps the most awkward of social conditions. Full of suggestion more than statement, the vignettes offer stylized interactions that may or may not seem opaque depending on the viewer. In any case, Rubberneck gives us something to look at even while perhaps making us pause to wonder why are so eager to find things to look at.

Rubberneck

Created, directed, and choreographed by Mattie McGarey

Producer: Sarah Cain; Costume Designer: Yunzhu Zeng; Lighting Designer: Taiga Christie; Composer & Sound Designer: Bailey Trierweiler; Sound Engineer: Anteo Fabris; Stage Manager: Leo Egger

Performers: Faizan Kareem, Xi Luo, Mattie McGarey, Hannah Neves, Adrianne Owings, Arnold Setiadi

Yale Cabaret

November 14-16, 2019