Third-year YSD director Dustin Wills’ thesis production of J. M. Barrie’s classic Peter Pan is everything a thesis show should be: a unique vision of a well-known work that revisits familiar (and not so familiar) terrain with a new perspective. Wills’ adaptation places Pan in an orphange during World War I, an alteration that creates an entirely different play. It’s also an exemplary thesis show in presenting resources of ensemble acting that set a new standard for the School, which does rather strive to get as many of its acting students involved in any project as possible. In Wills’ Pan, the actors play multiple roles but, in essence, each play one role: a child/orphan, enacting various parts in a child’s version of Peter Pan, and that entails marshaling all props themselves and creating before our wondering eyes all the necessary spaces and events of Peter’s adventures, from the house of the Darlings to a pirate ship, from a rock in the sea at rising tide to a battle with bayonets affixed—and, in Joey Moro’s ingenious design, lighting themselves, as well as seeming to construct Grier Coleman’s costumes ex tempore. The cast is so tremendously busy we have scarcely time to catch our breath, never mind how they do. And, with such a large cast—13—and so many events, it comes as a surprise how fast these two hours with no intermission pass. If you’ve attended many thesis shows then you know that what comes hardest is pacing. This Peter Pan must be pursued by the clock-containing crocodile, so well does it make use of its time.

Wills and his scenic designer, Mariana Sanchez Hernandez, present us with a set that is a testament to war-time austerity and dilapidation, with peeling, no doubt asbestos-ridden paint, hot water pipes overhead, opaque window panes, and uniform cots. The kids in the orphanage are in hopes of adoption and so their story of how a young girl comes to play mother for a host of Lost Boys in Neverland is at once a fantasy projection and a compensation. This innovation adds greatly to characters who, in the play, are simply take-offs on boyhood types, as these actors might, at any time, break character when something in the play strikes too close to home.

I don’t doubt that any parental types in the audience will arrive at a favorite they would gladly adopt—Tootles (Chris Bannow) is the most endearing, but there’s also the know-it-all, Curly (Aaron Luis Profumo), the preening Slightly (Aaron Bartz), the winsome Nibs (Maura Hooper), and the Twins (Hugh Farrell with a hand mirror and an authentic expression of dazed excitement); all also play Indians and/or pirates as required; then there are those who stay pretty much in one or two characters: Prema Cruz’s petulant Tinkerbell and regal Tiger Lily; Michelle McGregor’s blustering Smee and doting Mrs. Darling; Matthew McCollum’s thoughtful John; Mariko Nakasone’s feisty Michael, the baby of the family, and Sophie von Haselberg’s Wendy, a girl almost too mature for make-believe who playacts Mother in hopes of winning Peter’s heart.

Any might at any time step to the footlights and stammer something heartfelt; at one point, after hearing Wendy sing about what her ideal house would be like, all the kids rush to the edge of the stage to fling at us their individual visions of the home of their dreams. Such breaks in the orphans’ make-believe register a reality all are usually at pains to mask.

Their show begins with willful play-acting when “Mrs. Darling,” observes “her children” Wendy and John play-acting as their parents; soon enough the “real” Mr. Darling (Tom Pecinka) shows up and scolds everyone, especially the dog, Nana (Christopher Geary) who is banished from the nursery, thus setting up Peter’s arrival. What this production loses in whimsical magic—no “actual” elfin child floating into the room with fairy dust—it gains in the kinds of magical conjurations that children find in their collective imaginings—sheets as the sea, lifted beds indicating flight, characters pulled about on wagons and wheeled ladders. And forget the fey, androgynous Peters common to productions with a woman in the role; Mickey Theis’ Peter is robust and boyish, and when he takes on Hook (Pecinka) late in the play it feels like a boxing match as well as a duel to the death.

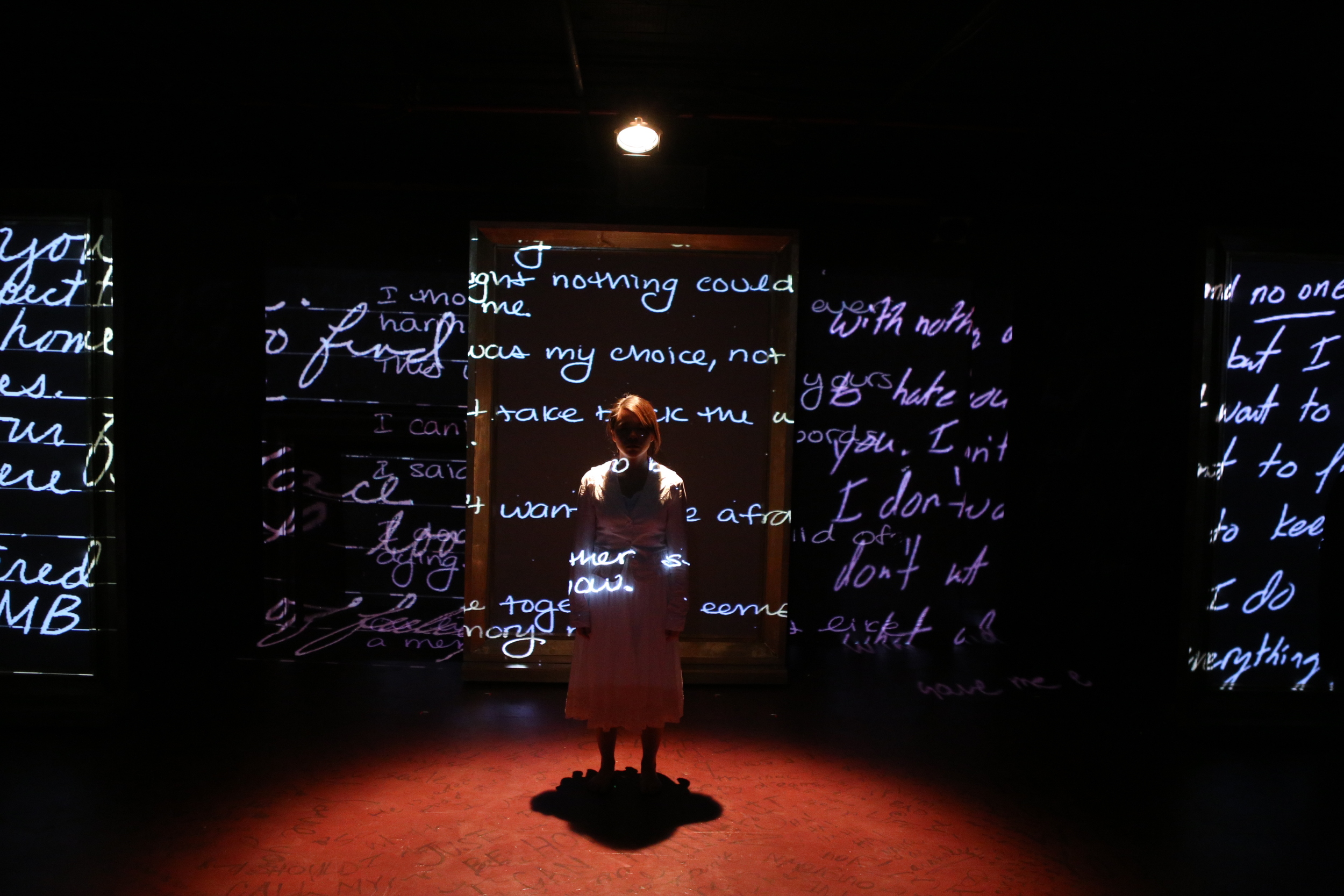

This is a very physical production, with tons of moving parts—some favorite moments are Wendy floating off the rock on a kite, the rock itself a mountain of valises; the props grabbed together to make the crocodile; Tootles’ stray shot with a real gun; the picture-book rescue of Peter from the rock by way of the Neverbird (Christopher Geary, looking like a downed airman—he is also relentlessly amusing as the pirate Starkey); everything said by Pecinka’s Hook, generally in a state of high dudgeon, letting envy of Peter’s fecklessness become, at last, thwarted love; near the end, Hook, in a fit of pique, threatens Peter with a “holocaust of children”—a potent phrase that seems to bring on a grim series of events that all the make-believe in the world can’t prevent. The final moments of the production flip into the nightmarish as children who don’t want to grow up become children who don’t get to.

Inventive, lively, and surprisingly serious, this Peter Pan lets us feel not only a very real cry for the cozy world of a mother’s care but makes us feel the threats to childhood that we should care about: the final images, set in the time of the Great War, can easily be transported to the time of the Blitz or to the sites of our contemporary drone strikes. Wills and company reach out from an orphans’ nursery—filled with children already missing important aspects of family and identity—to grab us with a sense of the atrocity that is the loss of innocence, and the loss of innocent lives.

This Peter Pan is not for children.

Peter Pan By J.M. Barrie Adapted and directed by Dustin Wills

Composer: Daniel Schlosberg; Scenic Designer: Mariana Sanchez Hernandez; Costume Designer: Grier Coleman; Lighting Designer: Joey Moro; Sound Designer: Tyler Kieffer; Production Dramaturg: Dana Tanner-Kennedy; Stage Manager: Anita Shastri

Yale School of Drama December 13-19, 2013