Review of Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again., Yale Cabaret

Billed as a play not “well behaved,” Alice Birch’s Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again. at Yale Cabaret, as directed by Jessica Rizzo with a cast of 12, behaves like a series of skits upon a theme: to revolutionize use of language and situational expectations. Each skit features a confrontation, in which characters—all, whether male or female, played here by women (with one exception)—address, more or less indirectly, a free-floating concept. The concept, we might say, is the unnamed elephant in the room, hovering like the array of pneumatic animals and toys that makes up the set. The elephant can be variously named—sexism, feminism, gender bias—but none of the terms do the amorphous creature full justice. And therein lies both frustration and courage.

The cast of Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again. (Photo: Elizabeth Green)

It takes courage to articulate what’s at stake in one’s dissatisfaction, and the problem of trying to compel understanding in others invites frustration. Birch’s dialogues run along lines that could be painfully raw if not for a certain manic undertone that most of the performers share. That’s not to say that all strike the same note, but rather than an overall tone of baring and sharing drives the show forward until it more or less explodes, then subsides in a kind of post-orgasmic clarity and depression.

The tone of a suppressed hilarity rising to the surface begins with the show’s amazing opening dialogue in which Nientara Anderson as, ostensibly, a man, and Mara Valderrama Guerra attempt to articulate the better-left-unspoken language of sex. And therein lies their problem. How do males and females think about sex, what vocabulary is accepted, permitted, arousing, disgusting, and so on? Like good sex, one assumes, it’s all a matter of intuition. Yeah, but. The dialogue plays out with increasing fervor until Anderson is cowering and broken and Guerra blissful in her self-absorption. You can only hope the pair work it out somehow.

Asu Erden, Flo Low (Photo: Elizabeth Green)

In the scenes that follow, two or three speakers try to find some common ground for the sake of communication, and Birch is very keen at showing how people having trouble communicating communicates in a big way. There’s Ariel Sibert who is trying to graciously—and anxiously—articulate her problems with Franci Virgili asking her to be his wife (she’ll become “chattel” or a means to lower his income tax), using a very wry analogy; there’s Asu Erden trying, not so graciously and not at all anxiously, to articulate to her supervisor, Flo Low, why she just doesn’t want to work on Mondays and can’t see a “work bar” as a “real thing”; there’s Ashley Chang and Emily Reeder as vigilant supermarket employees who try to be understanding while nearly going postal at Shadi Ghaheri as a woman who seems to have been masturbating with watermelons in an aisle of the store (Birch likes to keep references to watermelons, potatoes, bluebells, and cheese circulating through the text); and there’s Aneesha Kudtarkar as a mother and grandmother who denies she gave birth or has any descendants while Anderson, as her increasingly distraught offspring, tries to get inside her head while dealing with a daughter (Jiyeon Kim) who can’t seem to function. The open-ended terms in which these scenes can be played and interpreted is much the point. Here, the series begins comical and gets increasingly tense and dysfunctional as we go.

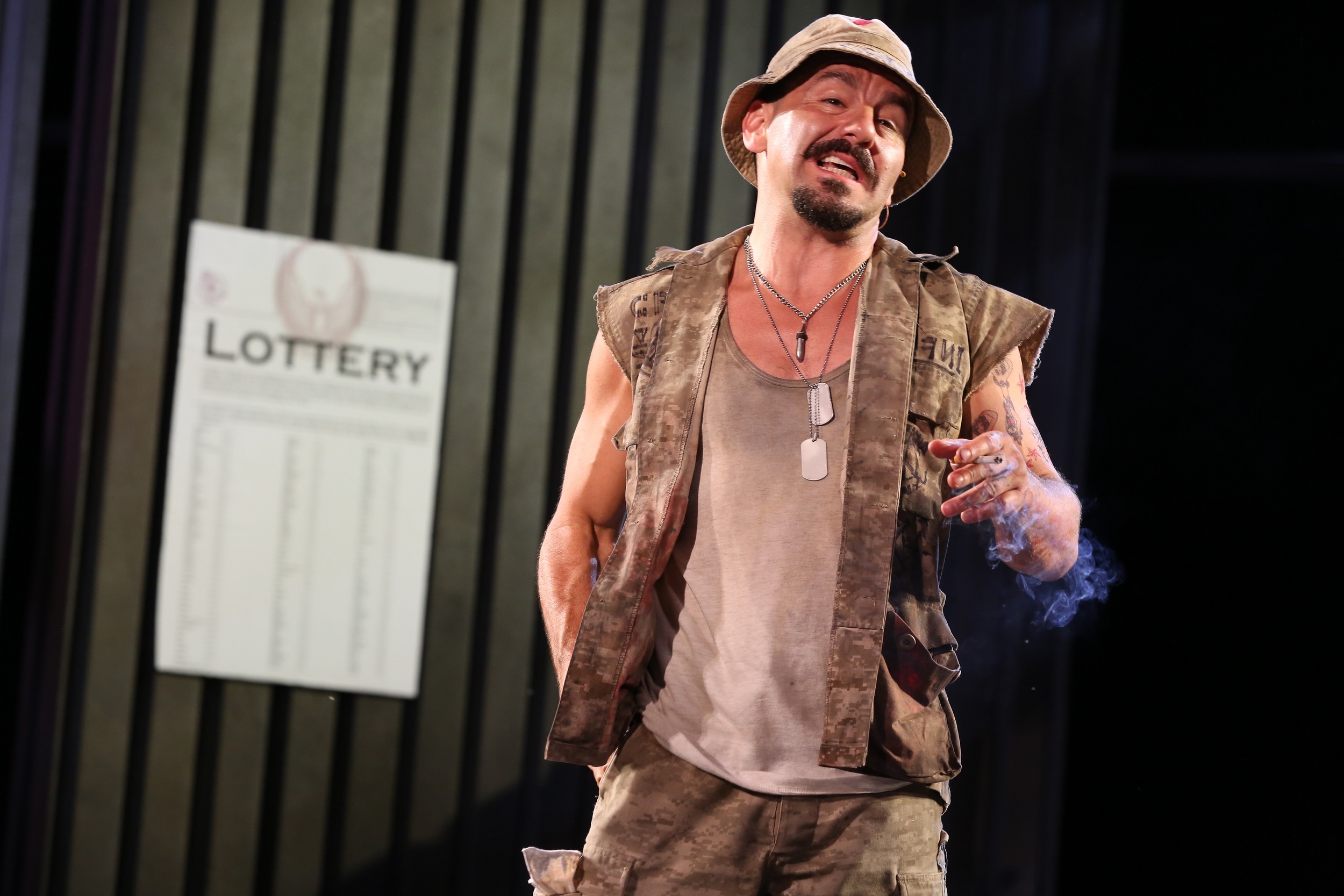

Nientara Anderson (Photo: Elizabeth Green)

The explosion of the entire cast beating on the inflatables while various mini scenarios get sounded—beginning with Guerra stating both proudly and plaintively that porn never arouses her—plays like a psychiatric session that encourages abusing toys as some kind of compensation or release. It’s a satisfying anarchic free-for-all, well choreographed though not well behaved.

Jiyeon Kim, Ariel Sibert (Photo: Elizabeth Green)

At various times in the show, projections of Mao-like slogans blare across the background to exhort changing the terms of work or sex or procreation. Between some of the scenes, composer Kim adds some vocalizing and, during the supermarket scene, a musical track accompanies the prone woman’s rant about trying to be wet and open so as not to be “invaded,” about reducing the border between her body and the world. The music becomes a striking presence, then subsides, leaving Chang to venture “I don’t know what happens now.”

Chang gets the last word at the end of the play as well, speaking up as at least four of the other women begin to plan a feminine utopia. Her comment sounds a deeply pessimistic note that seems to follow on Sibert’s musing that “the thought”—revolution, one supposes—is not enough. Which may be a way of anticipating the criticism that sounding off in plays may not really change anything, whether in the relations between the sexes or in the relations of production or of reproduction, or of viewer to viewed.

The play’s title seems to suggest as much with those definite full-stops. Revolt, followed by revolt again. Repeat as needed.

Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again.

By Alice Birch

Directed by Jessica Rizzo

Composer: Jiyeon Kim; Dramaturg: Ilinca Todorut; Set Designer: An-Lin Dauber; Costume Designer: Mika Eubanks; Lighting Designer: Samuel Chan Kwan Chi; Sound Designer: Christopher Ross-Ewart; Projections Designer: Asad Pervaiz; Stage Manager: Alexandra Cadena; Producers: Rachel Shuey and Caitlin Crombleholme

Cast: Nientara Anderson, Ashley Chang, Asu Erden, Shadi Ghaheri, Mara Valderrama Guerra, Jeremy O. Harris, Jiyeon Kim, Aneesha Kudtarkar, Flo Low, Emily Reeder, Ariel Sibert, Franci Virgili

Yale Cabaret

September 22-24, 2016