Review of Bulgaria! Revolt!, Yale School of Drama

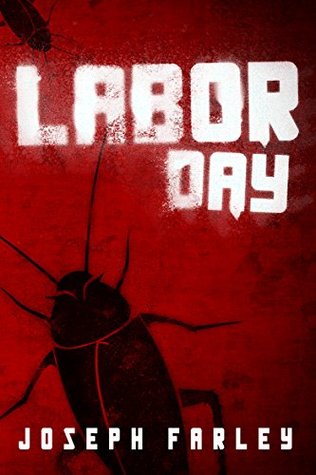

In Bulgaria! Revolt!, the wildly imaginative thesis show by third-year Yale School of Drama director Elizabeth Dinkova and her co-creator, third-year playwright Miranda Rose Hall, parody might seem the dominant mode. Parody of the traditional musical, certainly, but also of the more avant-garde versions that have come along at various times, including the Brechtian, and, in that vein, parody of the committed political drama. There’s a tongue-in-cheek quality that keeps us amused by a tale that traverses some unsavory aspects of 20th century history. In creating a musical that clearly favors the underdog—here the committed leftist poet Geo Milev, a casualty of a fascist regime, and his wife the actress Mila—Dinkova and Hall see clearly how difficult it would be to play the story with a straight face. Ours is a time best suited to burlesque.

And yet, it would be wrong to see the show as entirely parodic. Rather, Dinkova and Hall, with their composer and sound designer, Michael Costagliola, have concocted a musical that sustains its dramatic intentions while keeping its ironies in play. And that makes for a rather mercurial evening of theater, full of surprising turns and tones. The show incorporates the political history of Bulgaria, a deal with the devil, and the shameful working conditions in the Chicago meat-packing district in the 1920s. Ambitious? Yes, but that’s just another word for having a lot on its mind.

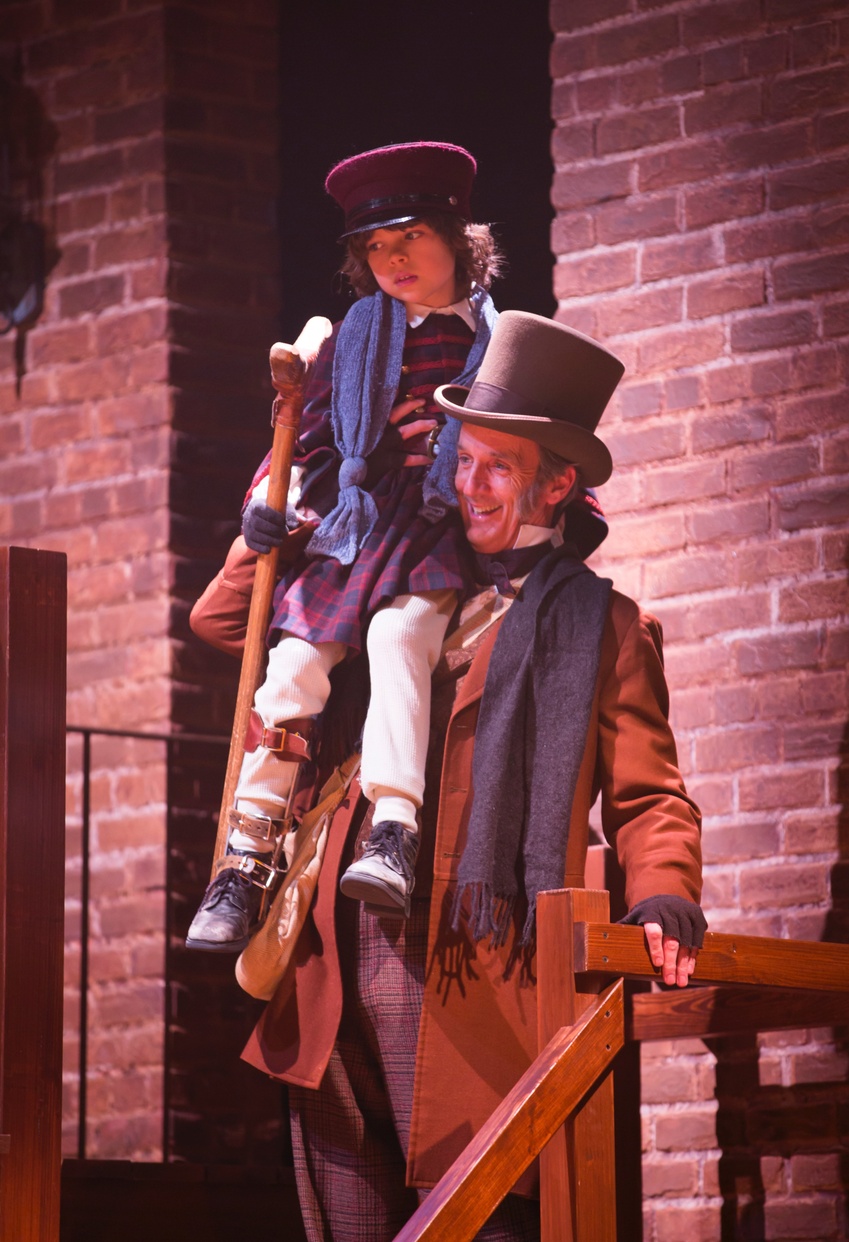

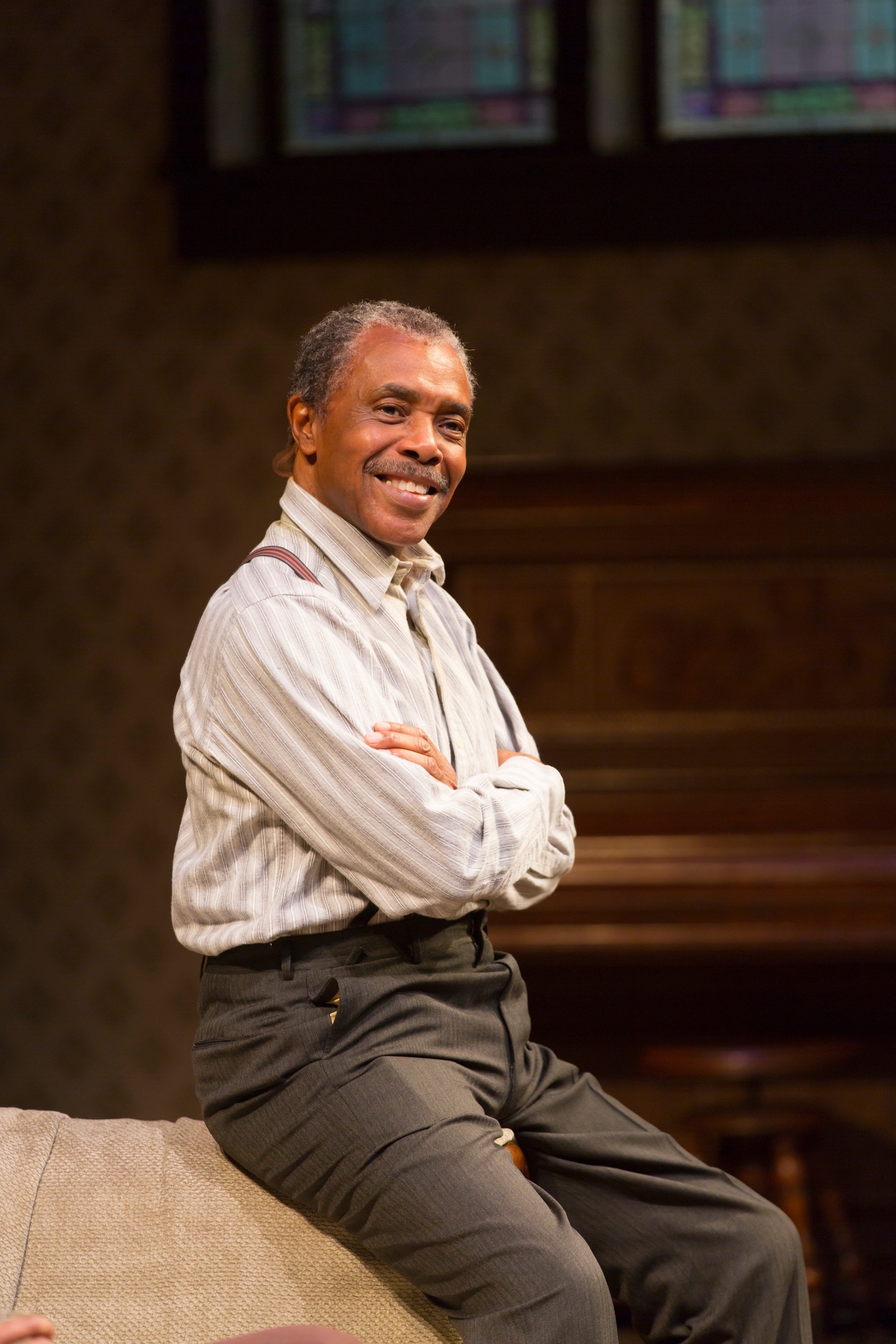

Ostensibly set in the 1920s, the story begins with its rather mild-mannered hero, the poet Geo (Leland Fowler), who is beside himself at the fact that his poem, September, about a recent brutally-suppressed peasant uprising, may cost him his life. His wife Mila (Juliana Canfield) sticks up for his poem’s value, but Geo wishes he could undo it. And, presto!, there to take advantage of his moment of weakness is the devil herself (Elizabeth Stahlmann), who casts them in her own version of a morality tale: As the poet Yanko, Geo will have the chance to undermine his own poem, meanwhile, as Miroslava, Mila will play the very soul of insurrection among the people.

The target of their revolt is now The Butcher (Dylan Frederick), a gleefully dissolute character who has his eye on Miroslava while imposing his whims on a gaggle of workers who seem as if they’ve stepped out of a Marx Brothers version of an Eisenstein classic: the Drunk (Ben Anderson), the Farmer (Sebastian Arboleda), an Old Witch (Marié Botha), the Historian (Anna Crivelli), an Old Priest (Jonathan Higginbotham), a Milkmaid (Courtney Jamison), the Tobacco Lady (Stephanie Machado), and a School Boy (Patrick Madden). Each is amusing in his or her own right while being forged into a collective by Miroslava’s spirited rebellion.

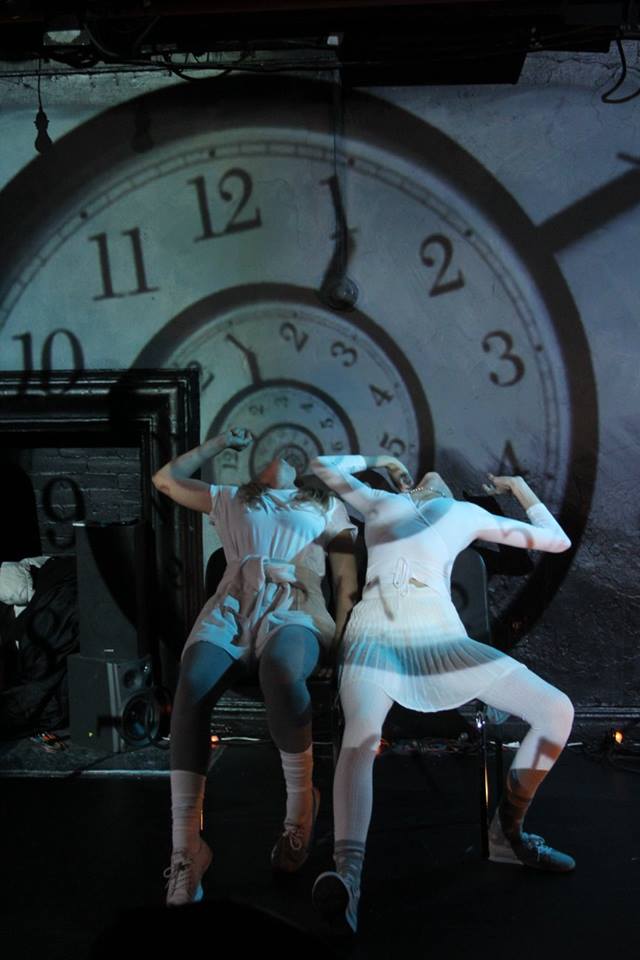

Canfield shines in her song of insurrection, like a rabble-rousing force of nature, and she’s matched by Crivelli’s dance of the many suppressions as the Historian reels off a chronology mind-boggling in its catalog of the many times hope for democratic freedoms has been beaten down in Bulgaria. And those are just some of the strengths of Act 1, which includes Frederick’s big number “The Butcher,” the comic highpoint. He’s attended by Stahlmann, who shape-shifts between brash devil and Toma, a fawning elder.

Yanko, shaken by the forces of violence aimed at The Butcher, takes the devil’s bait and decides to decamp for the U.S. Seemingly a victory for the devil, Act 1 ends with Mila insisting on another round, this time in Chicago, where everyone will be recast in a tale of her recounting.

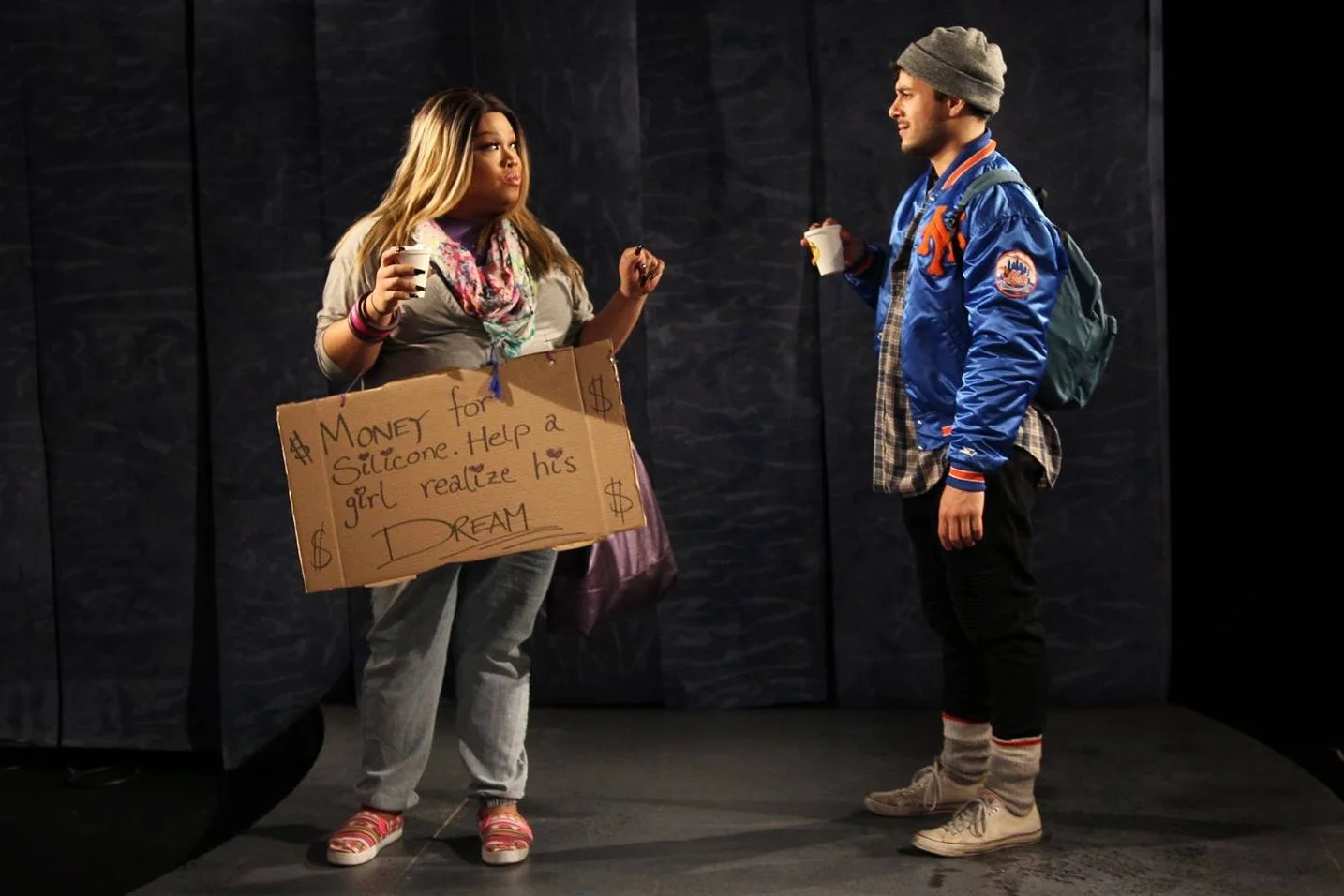

The notion of America as the land of the free is swiftly given the lie when we’re introduced to a host of immigrants from various lands—Poland, Ireland, South Africa, Italy, Mexico, to name a few—who toil under distressing conditions in the meat factory of Frank’s Famous Franks. Frank (Frederick) is, of course, “The Butcher” under new auspices, aided by his assistant Patty (Stahlmann, as the moral equivalent of a concentration camp commandant). A harrowing situation in Act 2 almost strips aside all the comic burlesque in favor of the most abject horror, and it’s a great tribute to Dinkova’s resources as a director that the show can shift toward the bathetic and recover its humor. In fact, the situation Dinkova and Hall create is a sharp commentary on the dehumanization of capitalist production at its most callous. And the cast—particularly Madden and Arboleda—are emotionally convincing in their grisly discovery.

Act 2 also boasts the most lyrical moment as Geo/Yanko and Mila/Sally sing a touching duet to their love, despite all. Indeed, Act 2 serves to vindicate Mila enough to rally the show into something like an upbeat register.

The scenic design by Emona Stoykova places the show on a platform surrounded by seats, making the action accessible in many directions, with, at one end, a hard-working pickup band being put through its paces and, at the other, an incredibly imposing portal. Lights and costumes and wonderfully involved projections—at times surveillance-style taping of the proceedings—add many lively effects, including childlike paintings that capture the folkloric quality of this varied tale.

Standouts in the show are Fowler’s pleasant singing voice, Canfield’s inspired ardor, Frederick’s zany villain, Crivelli’s rhapsody of history, and Stahlmann’s striking shifts among three characters, but it’s also a great ensemble show, and I’d be remiss not to mention Higginbotham’s brief-exposing pratfalls as the Old Priest and Machado’s Tobacco Lady saddled with a bevy of babies in slings. It’s the sort of show that has so much going on you’re bound to miss some of it in a single viewing.

It's unusual for a thesis show at YSD to be an original work, though it sometimes happens. Michael McQuilken’s Jib, an original musical from 2011 I remember fondly, is currently onstage in Philadelphia. May Bulgaria! Revolt! also find legs for future productions.

Bulgaria! Revolt!

Created by Elizabeth Dinkova and Miranda Rose Hall

Books and lyrics by Miranda Rose Hall

Music by Michael Costagliola

Directed by Elizabeth Dinkova

Choreographer: Christian Probst; Music Director: Scott Etan Feiner; Scenic Designer: Emona Stoykova; Costume Designer: Sarah Nietfeld; Lighting Designer: Krista Smith; Sound Designer: Michael Costagliola; Projection Designer: Wladimiro A. Woyno R.; Production Dramaturg: Maria Inês Marques; Technical Director: Kelly Pursley; Stage Manager: Shelby North

Cast: Ben Anderson, Sebastian Arboleda, Marié Botha, Juliana Canfield, Anna Crivelli, Leland Fowler, Dylan Frederick, Jonathan Higginbotham, Courtney Jamison, Stephanie Machado, Patrick Madden, Elizabeth Stahlmann

The Band: Alexander Casimiro, percussion; Allen Chang, clarinet; Ginna Doyle, violin; Scott Etan Feiner, piano; Jiji Kim, guitar; Adam Matlock, accordian; Ian Scot, bass

“Three Chains a Slave” performed by the Yale Slavic Chorus

Yale School of Drama

December 9-15, 2016