Preview of The Skin of Our Teeth at Yale School of Drama

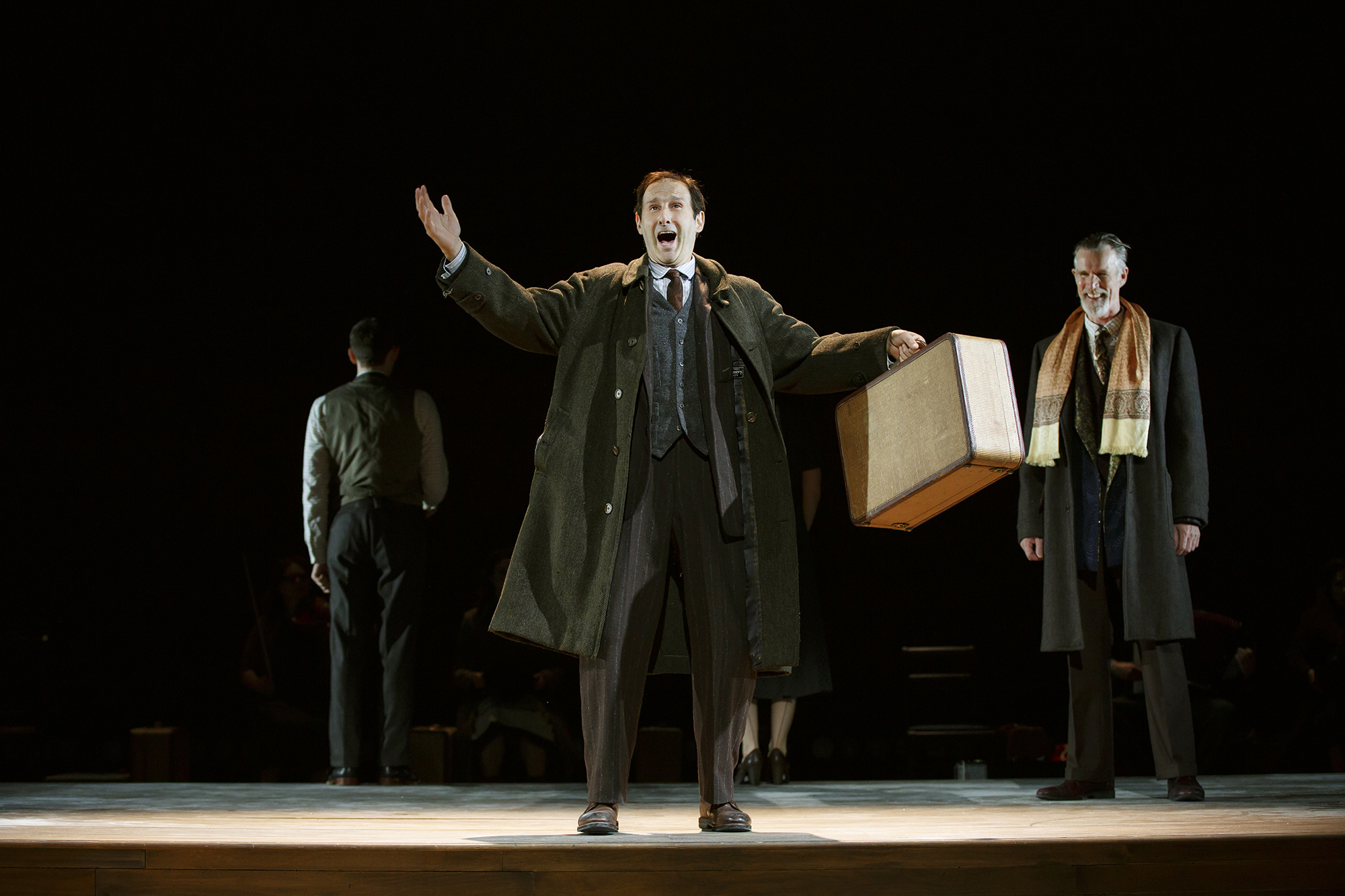

The first of this season’s thesis shows at the Yale School of Drama opens tonight. Third-year director Luke Harlan directs Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth, an unconventional play that caused some dismay with audiences when it opened, at the Shubert in New Haven, during World War 2. A view of the ages through the centering experience of an American family called the Antrobuses, the play, in good modernist fashion, toys with the conventions of theater while at the same time aiming for a theatrical experience that can be, in Harlan’s view, truly epic. It’s theme is no less than the survival of mankind on this distracted globe.

But, importantly for Harlan, it’s also very funny. Harlan cites some lines from Wilder that he came across in the Beinecke Library, which houses Wilder’s papers.

It is hard to imagine a man who occasionally does not suddenly see himself as both All men and The First Man. The two points of view are expressed for us by myths: at his marriage he may be reminded of Adam; when he goes about his house shutting windows against a rainstorm he is Noah; when he goes hunting, he calls himself Nimrod. The play tries to put this idea in dramatic form; and since it deals with both the individual Man and the Type Man, and deals with them in great trouble, isn’t it right that it should be fulll of anachronisms, indifferent to the smaller credibilities, be in all periods, and that it should be full of interruptions and accidents; and since Man is brave and enduring, isn’t it right that every now and then it should be gay?

From that brief summary, it’s clear that Wilder is thinking of biblical stories as the basis for our understanding of ourselves. In the sense of a palimpsest of personalities occurring throughout time, Wilder, who was a Yalelie, lived in Hamden, and hung out at the old Anchor bar across from the Shubert on College Street, was inspired by James Joyce’s “Work in Progress,” published in 1939 as Finnegans Wake. Wilder, like his master, takes a comic view of life, seeing mankind’s life as a human comedy in which Man plays many parts.

Luke Harlan

Harlan shares his playwright’s view of the value of comedy. He cites a contemporary entertainment like Jon Stewart’s Daily Show as an instance of how he sees the confluence of laughter and important issues. “We have to laugh at things to talk about them,” he says. Wilder’s play was written in a time of crisis when the outcome of the war was anything but certain, and before Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into the conflict. Then, In the post-war world, after the dropping of the two atomic bombs against Japan, Wilder’s play, with its post-apocalyptic Act III, seemed prescient.

For Harlan, who was looking for a thesis project that would be “epic” and “allow comment on current issues,” and “engage with discourse right now in the world,” one of the “anachronisms” that Wilder mentions could well be the issue of global warning. Even though Wilder is recalling the biblical flood, Harlan says, “it’s impossible for us not to think of” our threatened environment.

Asked what has changed in his conception of the play since he began working on it, Harlan says he’s become more aware of the importance of the family unit as represented in the play. The “70 year gap between Wilder and us” means that much has changed “in the gender dynamic.” The play is obviously focused on the father, as head of the family of 1940, but Harlan has come to realize the degree to which Mrs. Antrobus is the “rock of the family.” He believes that the amorphous quality of the play can allow for the differing family dynamics of 2015 without appearing too dated. Harlan does allow that “some of the language” and the reliance on “an early 20th-century framework” makes the play a bit quaint but insists that that effect is deliberate in Act I as Wilder seeks to establish “the old days.” By Act III and what Harlan calls “the postmodern world,” the language “doesn’t feel dated at all.”

In fact, he found, as he rehearsed and worked with his actors—a large cast of 13, including himself—that Wilder, as evidenced in his immensely popular play Our Town, is capable of “a simplicity that’s universal” with a use of language that “gets to the essential.”

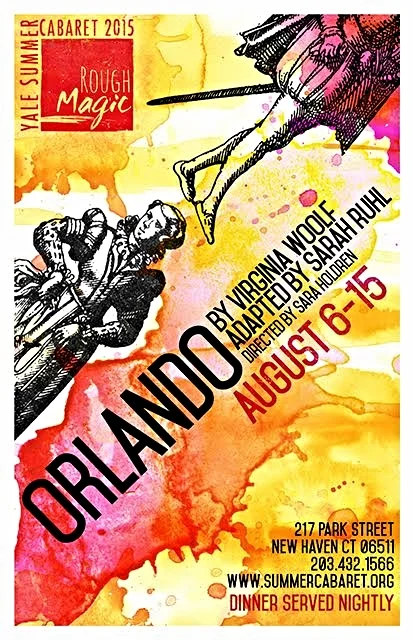

And the thought of Our Town is apropos. One of Harlan’s best successes while a student at the Drama School was in directing Will Eno’s Middletown for the Yale Summer Cabaret 2014, for which he was co-Artistic Director. That play took a very contemporary tone toward the small-town virtues of our mythic American life, with both humor and poignancy. He also directed, in the Shakespeare studio projects, A Winter’s Tale with a shifting and vivid palette of humor and pathos. The Skin of Our Teeth—the title is from the Book of Job—sounds like a timely project with the right ingredients for something wilder.

The Yale School of Drama presents

The Skin of Our Teeth

By Thornton Wilder

Directed by Luke Harlan

Scenic Designer: Choul Lee; Costume Designer: Haydee Zelideth; Lighting Designer: Carolina Ortiz Herrera; Sound Designer: Christopher Ross-Ewart; Projection Designer: Rasean Davonte Johnson; Dramaturg: David Clauson; Stage Manager: Paula R. Clarkson

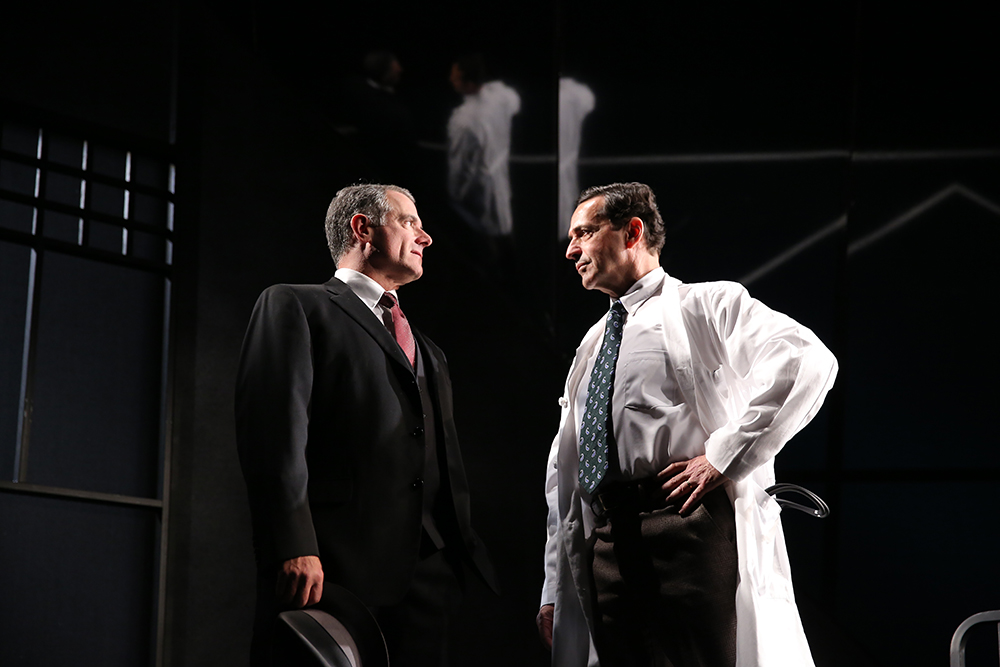

Cast: Andrew Burnap; Baize Buzan; Juliana Canfield; Paul Stillman Cooper; Anna Crivelli; Ricardo Dávila; Melanie Field; Dylan Frederick; Luke Harlan; Annelise Lawson; Jonathan Majors; Aubie Merrylees; Shaunette Renée Wilson

Yale Repertory Theatre

October 20-24, 2015