Review of Roberto Zucco at Yale Cabaret

Roberto Zucco, the eponymous hero of Bernard-Marie Koltès’ play, is a murderer, based on an actual twentysomething serial killer, Roberto Succo. Does a play about him glorify him? Not in itself, perhaps. We can watch plays like Macbeth or Richard III and accept that our hero will stop at nothing and has lost his moral compass. But in Koltès’ play, originally written in French and translated by Martin Crimp in the production at Yale Cabaret, there’s the further suggestion that, in modern society and perhaps in existence tout court, a moral compass is generally lacking. This makes a killer like Zucco, jarringly, an Everyman—a twisted, armed Everyman for whom violence is the solution to any situation.

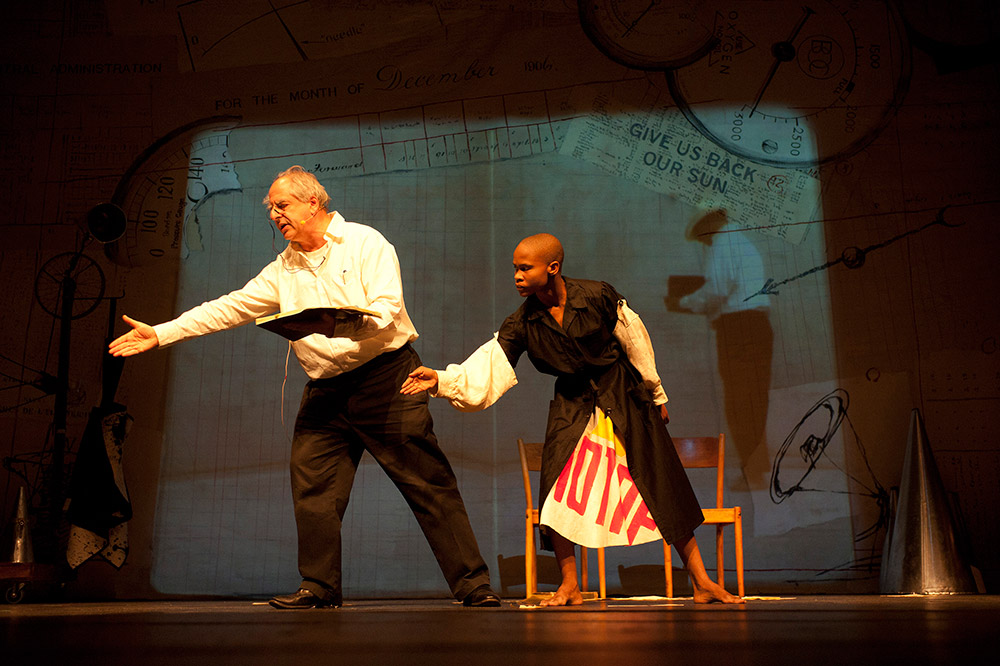

Perhaps to apprise us of the distortion in such a view of humanity, the Cab production, directed by Christopher Ghaffari, places the action on a raised rectangular platform surrounded by a not quite transparent scrim suspended from the ceiling. The audience, situated on all sides of the platform, sees the action through this opaque curtain—until late in the play when it is ripped aside—and that creates a distancing effect. The sense, very immediate at the Cab, that viewers and actors occupy the same space is set at a remove, with the effect that the events portrayed are placed a bit beyond our reach, as in memory or dream. The story of Zucco, then, is happening in a blurry space where clarity itself is lacking.

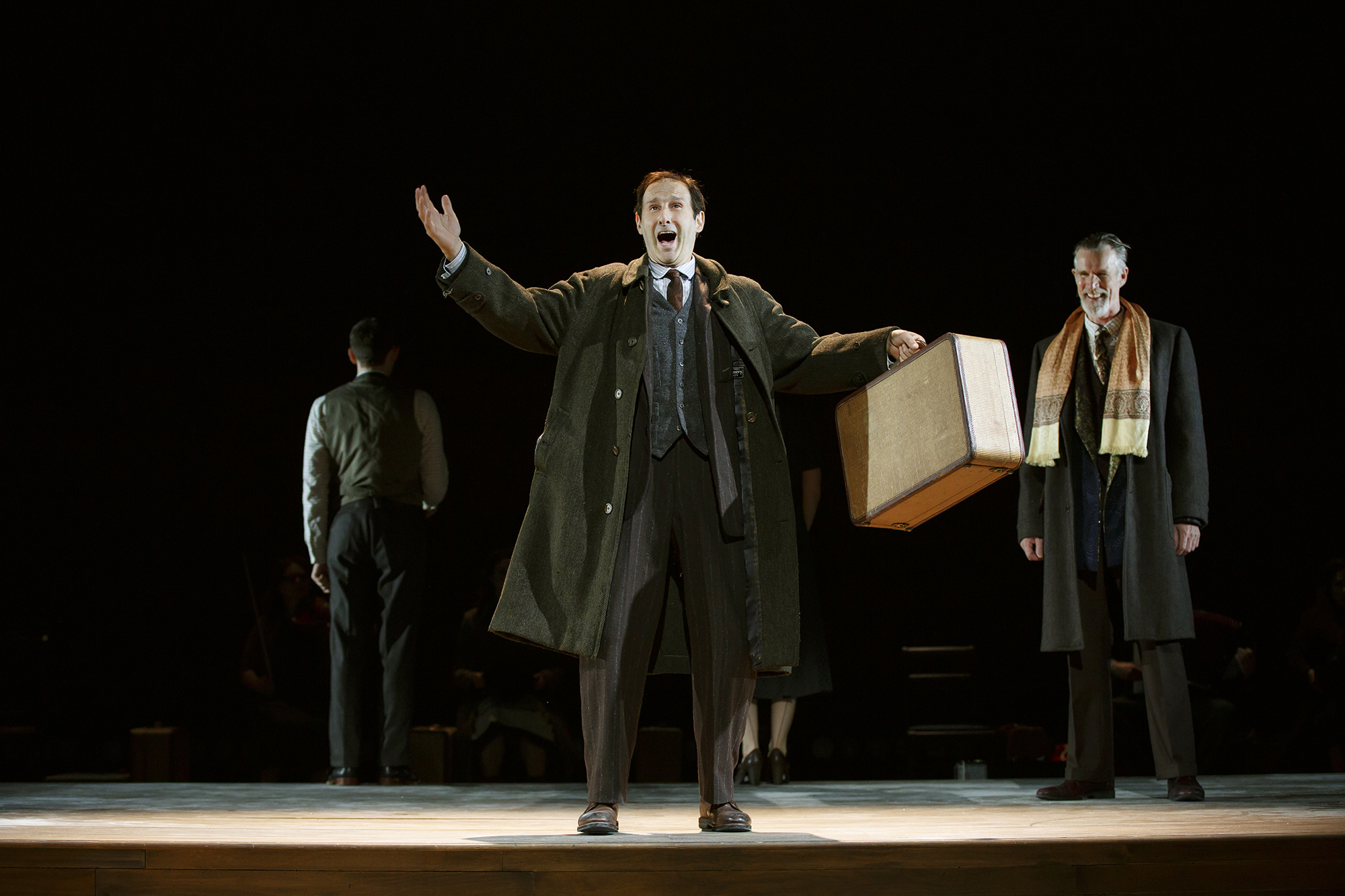

Then there’s the play’s language, often quite poetic, and its prevailing mood. Before we even meet Zucco, we hear the voices of the guards (Paul Cooper, Dylan Frederick) who realize that Zucco, an inmate jailed for the murder of his father, has escaped. The tone is clownish, and the feeling throughout is that Zucco is indeed a murdering fool. His recourse to violence, as when he visits his home to reclaim his battle fatigues and kills his mother (Brontë England-Nelson), is not premeditated so much as predetermined. Zucco is a killer—by nature or by inclination or by fate—and a killer kills, the way an attack dog attacks.

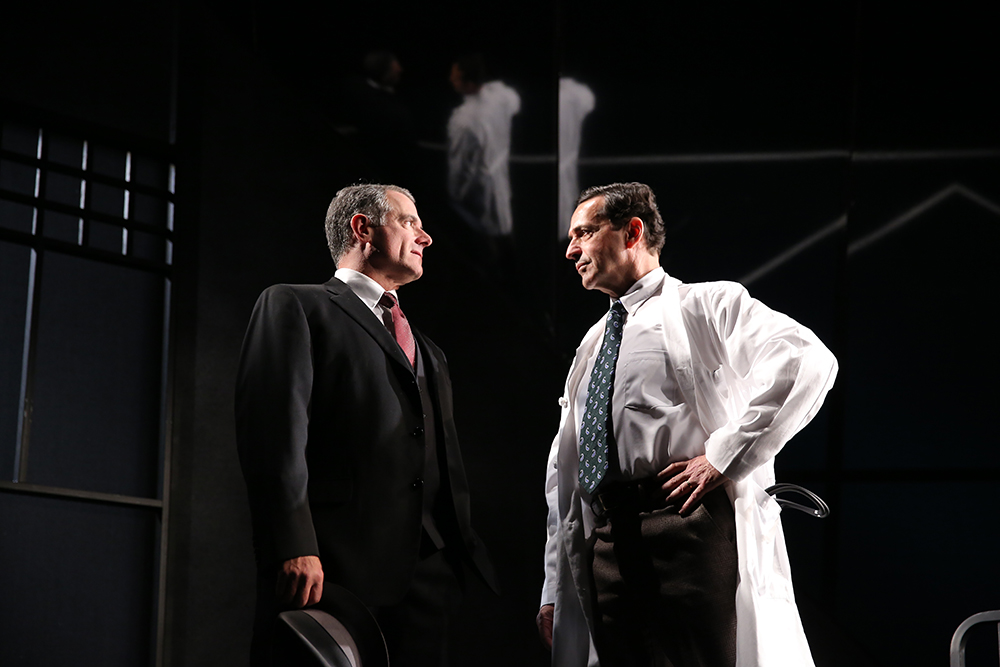

Aubie Merrylees as Roberto Zucco (photo by Christopher Thompson)

As played by Aubie Merrylees, Zucco is a “worst full of passionate intensity” but he is also, as when wooing Girl, a virginal innocent played with vacuous charm by Alyssa Miller, your basic mixed-up kid, full of chaos, uncertain about his own motivations, trying to be cool and mysterious (he tells her he’s “a secret agent”). Could someone like Zucco actually fall in love? Why not? And the family he tries to lure his sweetheart away from is dysfunctional with a laughable ugliness. The drunken, bullying father (Paul Cooper), the hapless mother (England-Nelson), the meddling older sister (Juliana Canfield), the sleazy brother (Jacob Osbourne) make us almost pull for “the couple.” And if it crosses your mind that maybe doing away with dad might actually be a good thing, well . . . .

But it seems that murder for Zucco is a spontaneous act (existentialists take note) and since there’s no confrontation with the girl’s father, there’s no showdown. A haphazard meeting once Zucco’s on the run again leads to a murder more jarring. Accosting a Lady (England-Nelson) on a park bench, Zucco gets lured by another trope of eros and things turn a bit more “Bonnie and Clyde”-ish. We don’t have to look too far to find instances of a killer’s charisma and Zucco apparently exudes it. But things go awry and spontaneous violence, while not exactly shocking us, creates a more psychotic wrinkle.

Not everything here works as well as it might. An interrogation scene with Girl feels a bit gratuitous and some of her wanderings take us into areas that seem hard to parse. The reigning logic by which a girl must remain virginal till marriage seems to hold here in its most virulent (no doubt Catholic) form, so that a girl who has been with a guy—not even a charismatic killer specifically—might as well become a prostitute forthwith. Which brings into the play prostitutes and pimps and at one point Zucco seems to be seeking some rough trade. Despite the effort to signal new characters via Asa Benally’s costume changes and Sam Suggs’ shifting musical cues, viewers, squinting through the curtain, might find themselves challenged in keeping different roles straight as most actors here play four—or in the case of Cooper five—roles. England-Nelson gets high marks for making each of her roles distinctly different and interesting, particularly a garrulous Old Gentleman, another of Zucco’s random encounters.

The randomness of much of this seems to be part of Koltès’ point, in as much as there’s no abiding logic to the course of events in the real world so why expect it in art. The finale comes—helped by floor-space projections by Rasean Davonte Johnson that shift from newspaper headlines to graphic images from Succo’s actual killings to a vertigo-inducing shrinking cloudscape—with Zucco, surrounded by officers and onlookers, finding his apotheosis, or is he simply ready for his close-up, Mr. DeMille?

The fact of terrorist massacres on the streets and in a well-known venue in Paris the very weekend of this production forcibly reminds us that there are killers among us, potentially, wherever we may be. Koltès’ play believes in evil and in innocence and wonders at collective contagions such as the thrill and release of violence, so ingrained into our pastimes and amusements and, yes, art, and the fawning fascination for the man with a gun or a bomb. While not directed at terrorism, per se, but rather at the case of the individual killer, the play suggests a world much like ours here in the States where random killings by lone gunmen proliferate virally. Sadly, Roberto Zucco remains a hero for our times.

Roberto Zucco

Written by Bernard-Marie Koltès

Translated by Martin Crimp

Directed by Christopher Ghaffari

Composer: Sam Suggs; Dramaturg: Ariel Sibert; Scenic Designer: Alexander Woodward; Costume Designer: Asa Benally; Lighting Designer: Andrew Griffin; Sound Designer: Ian Williams; Projections Designer: Rasean Davonte Johnson; Associate Sound Designer: Matthew Fisher; Technical Director: Willam Hartley; Stage Manager: Emely Zepeda; Producers: Tanmay Manohar, Gretchen Wright

Cast: Juliana Canfield, Paul Cooper, Brontë England-Nelson, Dylan Frederick, Aubie Merrylees, Alyssa Miller, Jacob Osbourne

Yale Cabaret

November 12-14, 2015