Review of Queens for a Year, Hartford Stage

Queens for a Year—the title comes from the scoffing phrase that male Marine recruits lob at female Marine recruits, with the idea that a woman in Boot Camp can always get away with less rigorous training than a man can—asks some tough questions about women in the military and about the ethos of the Marines specifically. T. D. Mitchell’s play, which is rather scatter-shot in its aims, mainly seems to want to pay tribute to women in the military—all the woman in the play who served or who are serving see their time in the military as definitive to their sense of worth—while also dramatizing the way that being female in the relentlessly masculinist world of the military means more hardship for female Marines rather than less. But the play also wants to take on the incidence of male assault on females, particularly in the Marines, and create a situation where the Marines’ “kill or be killed” ethos gets a dramatic staging. In other words, the play wants us to appreciate the military while also exposing its evils.

Charlotte Maier, Vanessa R. Butler, Heidi Armbruster in Queens for a Year (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

The play, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, is strongest in its support of women in the military. If we think that such a concern is fairly recent—say, since the invasion of Iraq or the invasion of Kuwait—Mitchell’s play lets us hear from four generations of women who served, going back to World War II. The play opens with Mae Walker (Mary Bacon) under intense questioning about a deliberately unclear incident that the play will dramatize. We then meet the Walker family when Mae’s daughter, 2nd Lt. Molly Solinas (Vanessa R. Butler), brings to her grandmother’s home in Virginia PFC Amanda Lewis (Sarah Nicole Deaver). The harrowing circumstances under which the two met is brought out gradually through flashbacks.

Meanwhile, the present time of the play (2007) is taken up with lots of small-talk and military reminiscence and getting acquainted, as Molly and her guest visit with Molly’s grandmother, Gunny Molly Walker (Charlotte Maier), great-grandmother, “Grandma Lu” (Alice Cannon), and aunt Lucy (Heidi Armbruster), Molly’s mother’s sister, who lets us know, in passing, that she was persona non grata for a time in the military for being gay. Eventually they are joined by Mae, who never got the military bug and here represents the civilian world and its uneasy acceptance of a militaristic worldview.

Grandma Lu (Alice Cannon), Mae (Mary Bacon), Lucy (Heidi Armbruster) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

The family matters are handled well and, since female soldiers are unusual in theater, that keeps our interest, particularly as it soon becomes clear that something happened on base and Molly and Amanda are on the run—or, more properly, Molly, as the only officer among them, has taken charge of Amanda and this is her way of coping with whatever is going on. The play’s second half, more dramatically but less satisfactorily, becomes a protracted stand-off; first, Mae introduces matters of family tension, and then a very real threat creates a siege situation, but, even then, the women make nice and burnish their family ties, with Alice Cannon enacting a favorite sentimental/comic cliché of the feisty old lady.

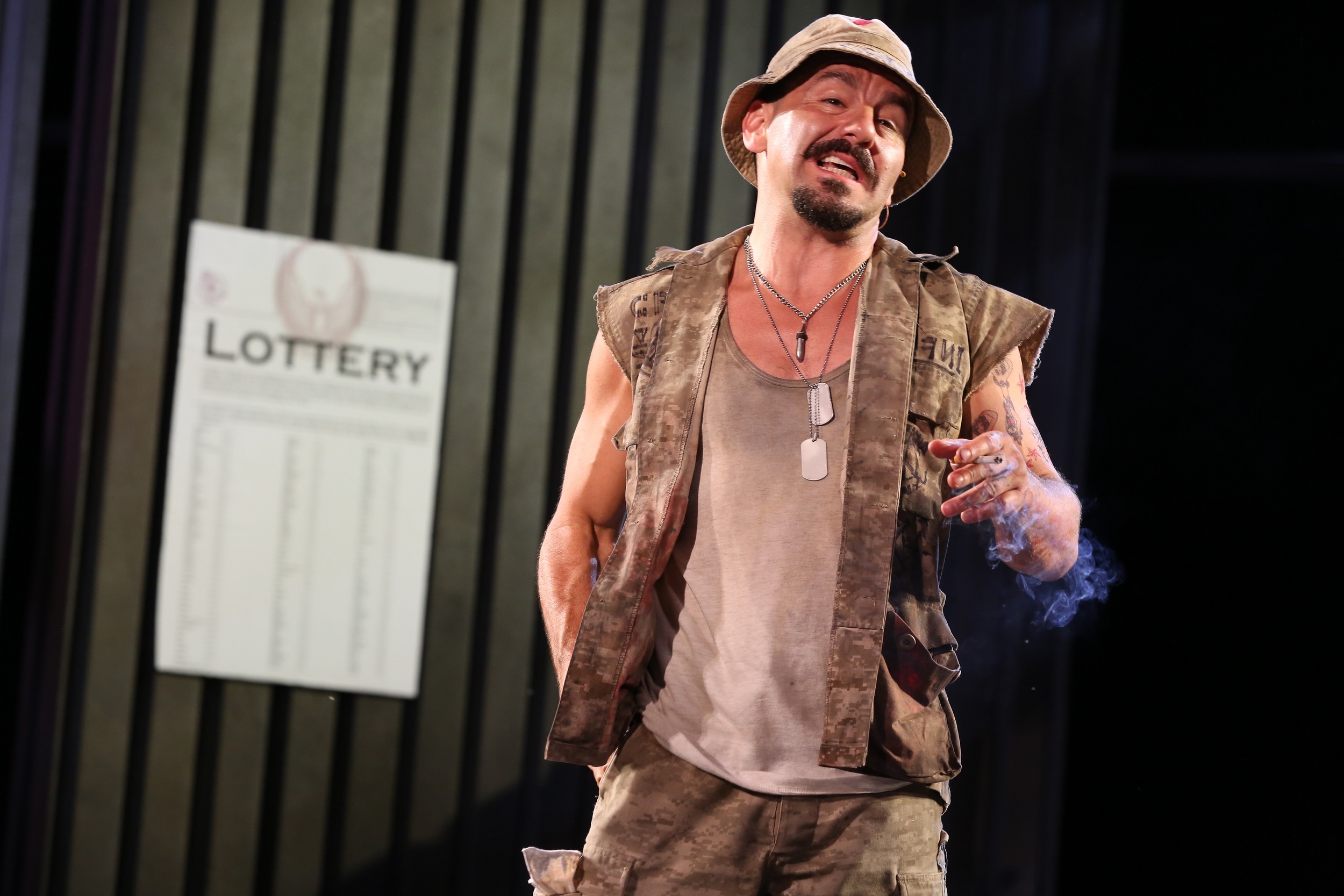

The flashbacks include Jamie Rezanour playing several parts—an Iraqi woman confronted by Lewis, an unsympathetic superior questioning Lt. Solinas, and a heartless military lawyer humiliating Lewis—and the show’s only male actor, Mat Hostetler, playing an unsympathetic and leering superior questioning Lewis; both actors also play nameless soldiers who stride about reciting “cadences,” mostly scurrilous sexist and racist shout-outs to keep time on march. Somewhat jarring to the bonhomie on view in the Walker home, these scenes suggest, and possibly belabor, how far removed a military life is from the comforts of home.

Jamie Rezanour, Sarah Nicole Deaver (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

At the heart of the play is the question that underlies all the drama surrounding Lewis’ plight and Lt. Solinas’ means of dealing with it: how can the corps drill into its members unflinching loyalty to the corps while at the same time being so abusive and dismissive toward some members of the corps? But then a sensitive grasp of the paradox of an individual within a collective might not be something we expect of the military. Mitchell tries to let action speak for itself, but, apart from the deliberately leading interrogations, there’s precious little occasion for anyone to explain what they think and why. And that might be one of the more telling qualities of the play: it shows us a group who tend to think they all think the same way, mostly, and then to have that consensus tested by enemies without and within is, one way or another, a moment of truth.

Molly (Vanessa R. Butler), and Mae (Mary Bacon) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Butler and Deaver come off well in their bonding and in the differences that keep them wary, though Butler is the more convincing as a servicewoman. Daniel Conway’s scenic design is very effective in placing a homey farmhouse in the midst of outlying areas that can become Camp Lejeune or Iraq, as needed—the sand and sandbags on the perimeter and on the catwalk above help to keep us apprised of the fact that all our homey spaces are surrounded by the perimeters our military guards. And Greg Webster’s fight designs work at times with almost cinematic fluidity.

The disengage between peaceful lives and life at war we can expect to be brutal and decisive; Queens for a Year looks at the wars that go on in the midst of the struggle to form warriors, with all the bravura and mixed feelings and uneasiness that task elicits, and all the opportunities for courage and honor, and for behavior squalid and vicious. Sexism, like racism, the play implies, sees enemies in the midst of the collective, and that, from the point of view of corps solidarity, is a tremendous weakness.

Queens for a Year

By T.D. Mitchell

Directed by Lucie Tiberghien

Scenic Design: Daniel Conway; Costume Design: Beth Goldenberg; Lighting Design: Robert Perry; Sound Design: Victoria Deiorio; Wig Design: Jodi Stone; Dramaturg: Elizabeth Williamson; Fight Director: Greg Webster; Dialect Coach: Robert H. Davis; Casting: Binder Casting, Jack Bowdan, CSA

Cast: Mary Bacon, Vanessa R. Butler, Sarah Nicole Deaver, Charlotte Maier, Heidi Armbruster, Alice Cannon, Jamie Rezanour, Mat Hostetler

Hartford Stage

September 8-October 2, 2016